Bible, History, Archaeology

History,

Archaeology

Home >

Deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphic writing

Introduction

The first discovery was the deciphering of hieroglyphics in 1822 by Jean-François Champollion (1790-1841). The decree in question is that of Ptolemy V, 196 BC.

This decipherment was mainly based on a drawing taken from a stele known as the Rosetta Stone, discovered at Rosetta in the Nile Delta in Egypt by a French army officer and handed over to the English as a surrender tribute during Bonaparte's military campaign in Egypt (1798-1801).. The campaign did, however, lead to an advance in scientific, cultural and artistic knowledge of ancient Egyptian civilization, thanks to the 167 scientists who accompanied the French army, including the French mathematician G. Monge and the French chemist C. L. Berthollet and Dominique-Vivant Denon, who became the first director of the Louvre museum. This expedition of scientists and intellectuals drew the first complete picture of Egypt, raising maps.

The deciphering of hieroglyphics was like opening a door to the history of ancient Egypt. The frescoes that covered palaces, monuments and temples finally became comprehensible to us. These elements, which serve as the backdrop to several episodes in the biblical story, shed new light on and give us a better understanding of the Scriptures.

It's also interesting to note that the word pharaoh, which appeared during the New Kingdom (circa 1550-1069 BC), was handed down to us by the Greek translation of the Bible, the Septuagint, and comes from the Egyptian per-aâ, which literally means «great house» or «palace». This term came to be confused with the person of the king, much as the French say ’Élysée« to designate the residence of the President of the Republic, the presidential function and the President himself.

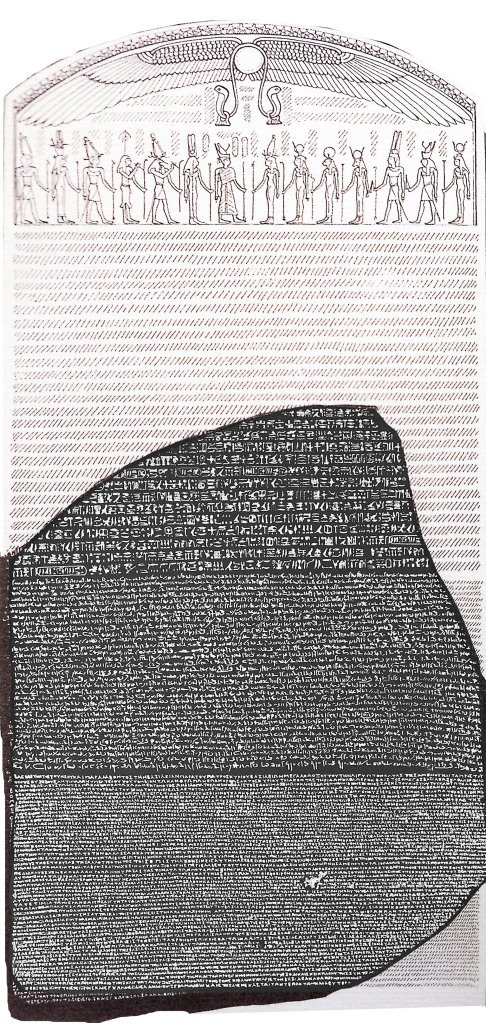

Image opposite: proposed reconstruction of the original stele with the fragment of the Rosetta Stone. DR.

Its presentation

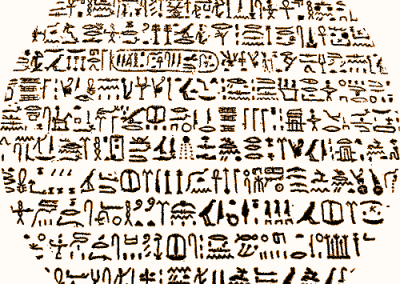

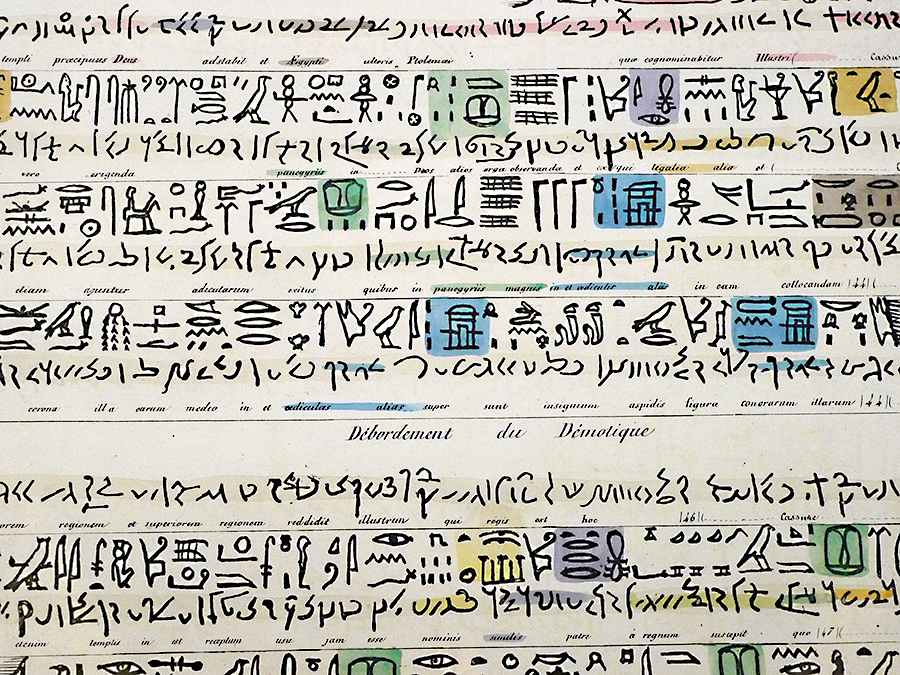

Image opposite: a study sheet on Egyptian hieroglyphs by J.F. Champollion. Musée de Figeac. Théo Truschel.

The stone measures 112.3 × 75.7 cm and is 28.4 cm thick. The stele is made of granodiorite, a material frequently mistaken for basalt or granite.

Originally displayed in a temple, the stele was probably moved in the early Christian era or during the Middle Ages, and later used as building material for fortifications in the Nile delta town of Rosette, renamed Fort Jullien by Bonaparte in memory of his aide-de-camp Thomas Prosper Jullien, who died during the campaign. It was rediscovered in this fort on July 15, 1799 by a French officer, Lieutenant Pierre-François-Xavier Bouchard, during Bonaparte's Egyptian campaign. The first known bilingual Egyptian text, the Rosetta Stone quickly aroused public interest because of its potential for the translation of hitherto undeciphered ancient Egyptian languages. Copies and casts circulated among European museums and scholars. Meanwhile, Bonaparte was defeated in Egypt and the original stone became a British possession in 1801. Transported to London and exhibited at the British Museum from 1802, it is one of the museum's flagship objects.

Its translation

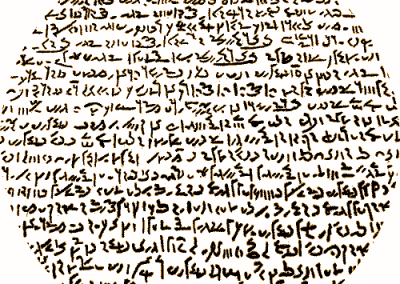

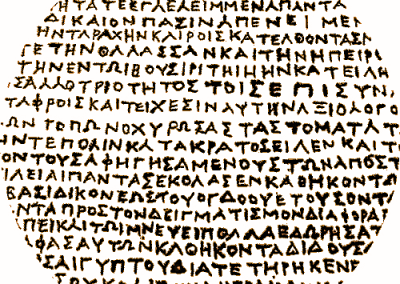

Image opposite: near the Musée des Écritures de Figeac, Joseph Kosuth has created a huge reproduction of the Rosetta Stone, which fits in remarkably well with the architecture of the town of Figeac. The three scripts, hieroglyphic, demotic and Greek, are laid out on the floor. This representation of writing in urban space is a veritable metaphor for the work of Champollion, who devoted his short life to the hidden meaning of hieroglyphs and to knowledge of their cultural and social milieu. © Théo Truschel.

The main decryption steps were :

- recognition that the stone contains three versions of the same text (in 1799); ;

- the fact that the demotic text transcribes foreign names phonetically (1802) and that the hieroglyphic text does the same and bears important resemblances to demotic (Thomas Young, 1802); ;

- finally, the understanding that hieroglyphic text also uses phonetic characters to write Egyptian words (Champollion, 1822-1824). Since its rediscovery, the Rosetta Stone has been the subject of numerous national rivalries, including the change of ownership from France to England during the Napoleonic Wars, long-running controversies over the respective contributions of Young and Champollion to its decipherment, and, since 2003, Egypt's request for its return to its country of origin.

Two other fragmentary copies of the same decree were later discovered, along with several bilingual or trilingual Egyptian texts, including two slightly earlier Ptolemaic decrees (the Canopic Decree and the Memphis Decree). The Rosetta Stone is no longer a unique piece, but its role has been essential to modern understanding of ancient Egyptian literature and civilization in general.

A view of Guizet and its three pyramids: Khéops, Khéphren and Mykérinos, 25 km from Cairo, Egypt © Marcel Winger.

The second discovery

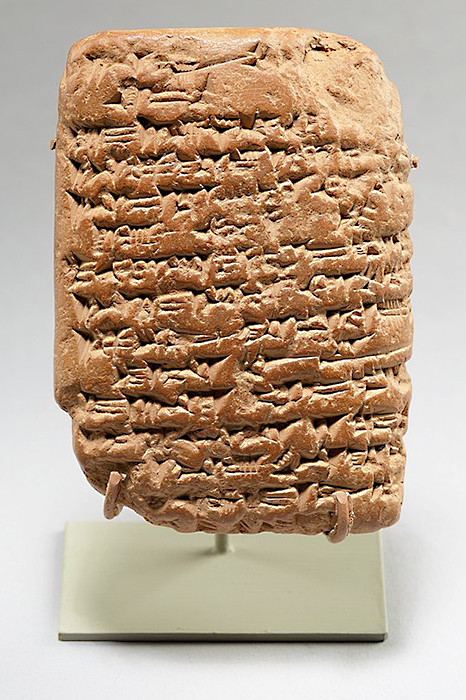

The second discovery was the deciphering of cuneiform script, the writing of Sumerian, Assyrian, Babylonian and Medo-Persian civilizations. The first approach was made in the early 19th century by G. F. Grotenfed, who began the first decipherments of the three cuneiform languages: Old Persian, Elamite and Akkadian (Babylonian).

The third discovery

The third discovery was made by a farmer in 1887, more than 350 clay tablets in cuneiform script at the Tell El-Amarna site, in Egypt, the former capital of Pharaoh Amenophis IV, also known as Akhenaton.