Bible, History, Archaeology

History,

Archaeology

Home > Artifacts > AT artifacts >

The ivory pomegranate,

a paleo-Hebrew inscription

Contents:

Introduction - Presentation - What is the date of this object? - A view of the ivory pomegranate - What is its function? - But what does the inscription say? - Publication and reactions - Divergence and questioning - Artifact description and analysis - The first letter - The second letter - The third letter - A new hypothesis - Registration and translation - Conclusion

In the summer of 1979, as he does every time he comes to Jerusalem, epigraphist André Lemaire, director of studies at the EPHE, makes the rounds of the antiquities dealers in the old Arab city. One of the antiquarians asked him to meet him in a back store to show him an artefact. The dealer revealed an ivory pomegranate, no bigger than his thumb, with an inscription in ancient Hebrew.

André Lemaire obtains permission to photograph it so that he can study it closely.

Presentation

Presentation

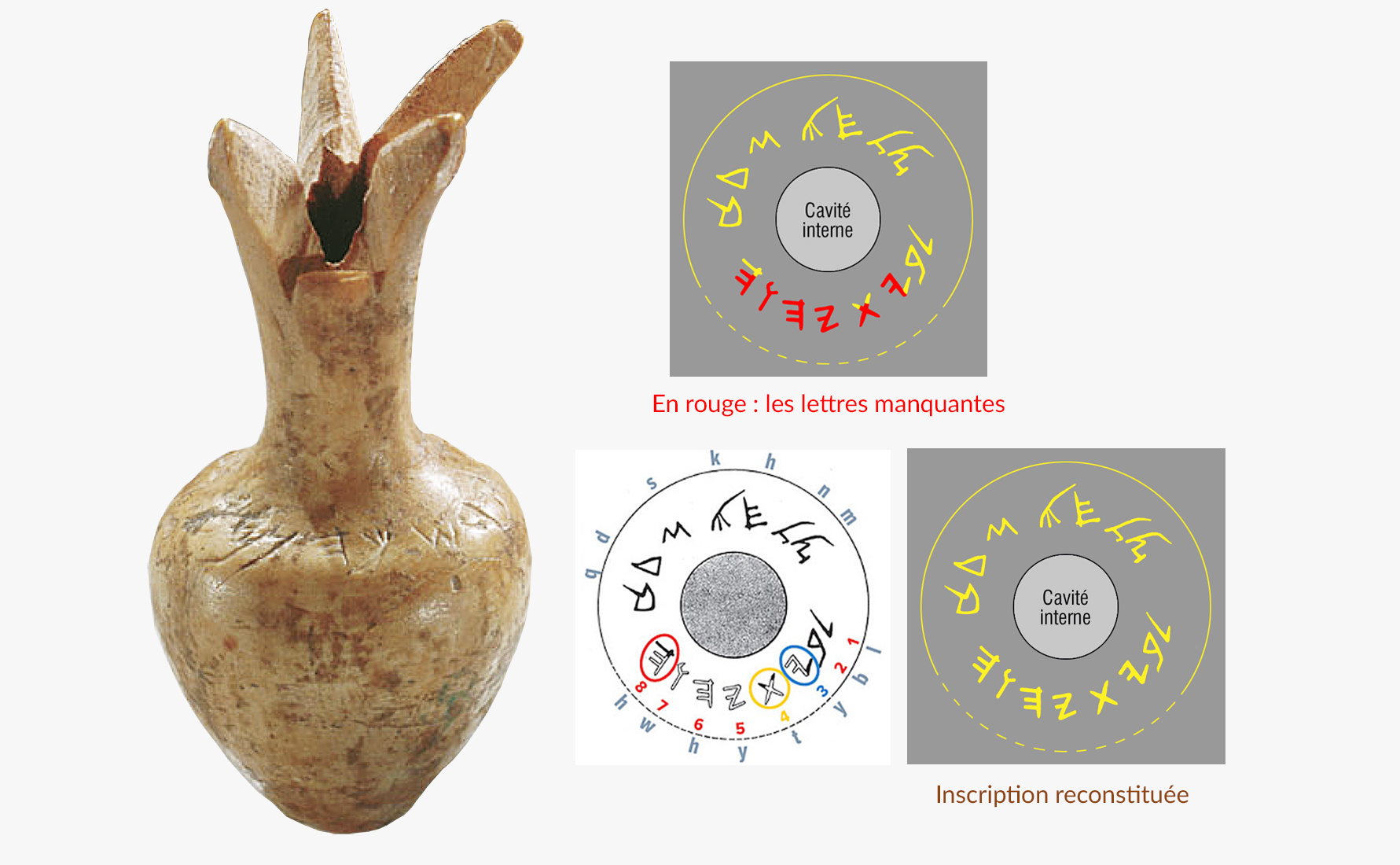

This hippopotamus ivory object, 43 mm high and 21 mm in diameter, has the shape of an elongated grenade, topped by six petals, two of which are broken. The body of the grenade has also been partially fractured.

The base features a hole measuring 6 mm in diameter and approximately 10 mm deep. On the top of the curved part of the pomegranate, around the elongated neck that produces the petals, is an incised inscription that is partly incomplete.

Image opposite: the pomegranate has a hole at its base, probably to be fitted onto some kind of rod (ivory or wood?) and used as a scepter. From left to right, the broken part and, on the right, the partially unscathed part. Israel Antiquities Authority. Montage Théo Truschel.

How old is this object?

The shape of the letters refers to a famous inscription engraved on the wall of the Siloam tunnel dug in Jerusalem by King Hezekiah of Judah, around 705 BC (2) Kings 20,20). Here again, the epigraphist works by comparison. Frank Cross of Harvard University confirms the dating, to within fifty years.

An image of the pomegranate with its inscription: © Israel Museum, Jerusalem. Biblical Archaeology Review.

What is its function?

Image opposite: the pomegranate is a red fruit with numerous seeds, themselves ruby-colored, linked to blood, life and fertility. Public domain.

The pomegranate is also an important element in the biblical tradition that describes certain elements of the first Temple. We read that garlands of 400 pomegranates adorned the capitals of the two bronze columns that sat at the entrance to the sanctuary (1 Kings 7,20), and also, concerning the ceremonial tunic of the high priest: «a golden bell, a pomegranate, a golden bell, a pomegranate, on the sides of the robe all around». (Exodus 28,34).

At the end of the 8th century B.C., the Judeans apparently had just one temple, the one built by Solomon in Jerusalem.

This small engraved ivory pomegranate could perhaps be the final decoration on a «sceptre» used by priests in a "holy age". Yahvist temple or, at least, kept as a precious object in its «treasury», probably that of Jerusalem, towards the end of the 8th century BC.

But what does the inscription say?

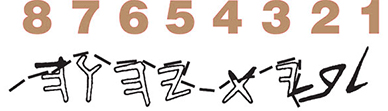

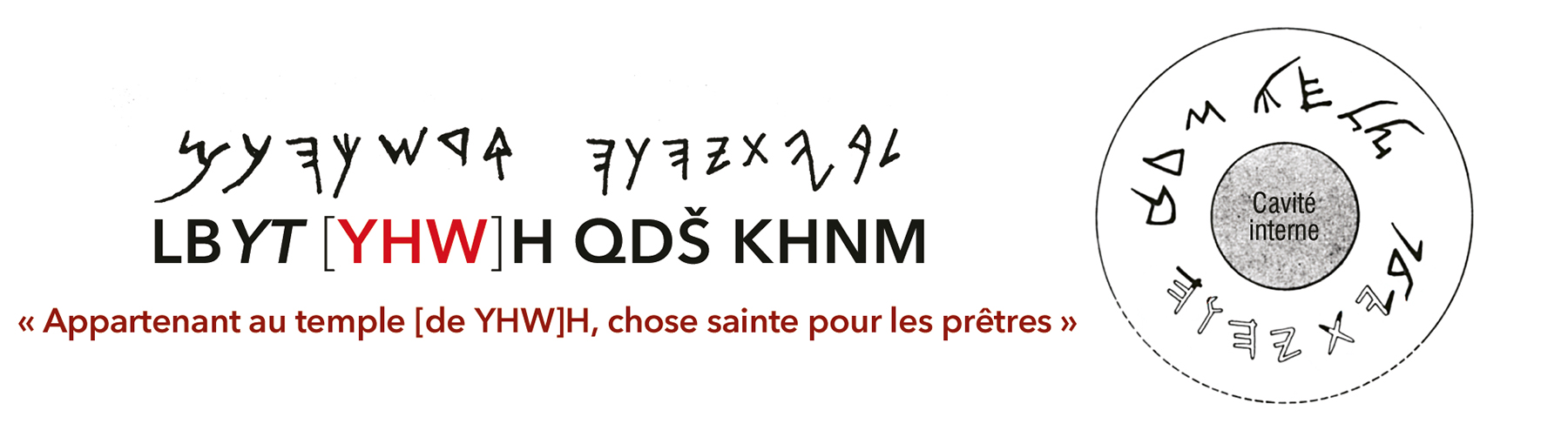

Professor André Lemaire reconstructs the incised text letter by letter. LBYT - a missing part - an H, then QDŠ, then KHNM. The missing part could correspond to a three-letter space. The inscription reads as follows:

LBYT- - -HQDŠKHNM

André Lemaire then recalls an inscription found on a shard of pottery unearthed at Arad (Negev desert) in the ruins of a fortress. It bears the letters BYT YHWH - meaning «temple of Yahweh». It's tempting to replace the three missing letters on the pomegranate with the same ones as on the ostracon, i.e.: YHW, especially as there may be a tiny trace of the top of the W.

The inscription now reads:

LBYT [YHW]H QDŠ KHNM

And can be translated as :

«belonging to the Temple [of YHW]H, a holy thing for the priests» or according to the interpretation proposed by Nahman Avigad: «sacred gift for the priests of the house of Yahweh». This interpretation was not adopted by J. Renz and has been criticized until recently.

Publication and reactions

André Lemaire's study was published in 1981 in a scientific journal. There was no echo outside specialist circles. The case would have remained in the shadows of libraries, had it not been for a famous American magazine. Biblical Archeology Review (BAR) did not publish André Lemaire's article in 1984. The subject of the article aroused great emotion in the United States and Israel. Thus, it would remain an object, a single and unique object of the Solomon's Temple, a sacred landmark in the history and religion of the Jewish people?

For, despite hundreds of excavations, no direct archaeological evidence of the existence of the First Temple has never been exhumed.

Then the panic sets in: where is this priceless treasure?

In Israel, the best investigators set out to find him. The dealer who had contacted A. Lemaire claims to have dealt only with intermediaries and not to know the identity of the owner.

As André Lemaire had already anticipated, the grenade was probably unearthed by a worker at an archaeological site near Jerusalem, or removed from a tomb by bulldozers or looters. Investigators are trying to trace the trafficking of ancient objects. In vain: the grenade has indeed disappeared.

André Lemaire found it quite by chance at the Salon du Livre in Paris in 1985. Yes, there it was, on display for thousands of visitors to see.

From then on, specialists from the Israel Museum re-launched the investigation. After many twists and turns, the grenade was once again spotted. One of Israel's leading archaeologists, Nahman Avigad of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who had recognized the grenade's authenticity, arrived in person in Switzerland to negotiate the purchase. The price demanded by the dealer exceeded the Israel Museum's possibilities, but an anonymous donor sent him a cheque for the requested amount. The grenade finally returned to Israel.

Divergence and questioning

The pomegranate becomes the subject of a controversy that divides the scientific world. Following a number of cases of possible counterfeiting, such as the’Ossuary of James, son of Joseph brother of Jesus or the Tablet of Joas, the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) and the Israel Museum in Jerusalem decided to form a committee of experts to reassess the authenticity of the ivory pomegranate. The conclusion of their report was published in the Israel Exploration Journal in 2004: in fact, they all agreed on the authenticity of the grenade itself, which, according to the Lakish parallels, probably dates from around 1200 BC. Careful examination reveals the presence of a calcite veil, such as can form on objects that have been in a tomb for centuries. However, it is the age of the inscription itself that poses a problem.

On the initiative of Hershel Shanks, editor of the magazine BAR, A new analysis was proposed to the members of the expert commission, who finally accepted it, albeit with some reservations. The date was set for May 3, 2007, at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

Artifact description and analysis

The inscription, engraved around the shoulder of the pomegranate, consists of two parts: on one side, the first text: «(belonging) to the Temple of Yahweh»; on the other side, the second text, «Holy for the priests». While the latter part of the inscription is perfectly legible and poses no particular problem, the first text raises questions. Unfortunately, around a third of the pomegranate's body broke off in antiquity, leaving only traces of the letters of the expression «temple of Yahweh», which scientists are trying to restore.

Image opposite: the stereoscopic microscope used to analyze the partial letters. The pomegranate (circled in red) can be seen under the microscope. Biblical Archaeology Review.

The letters are in Paleo-Hebrew, the script used by the Israelites to write Hebrew before the destruction of the Temple in 586 BC. It is read, as Hebrew is today, from right to left.

The first part of the inscription consists of two words: lbyt [Yhw]h, belonging to the house of Yahweh«. Letters 1 and 2 are complete. Letters 5, 6 and possibly 7 are completely missing. Letters 3, 4 and 8 are partially present.

Can these three partial letters reveal whether the inscription is the work of a modern forger, or is it ancient and therefore authentic?

All committee members agree that the main fracture in the grenade is quite old. But two additional fractures appear to be more recent. Explaining when and how these modern fractures occurred is a puzzle. The panel suggests the following scenario: when the forger cut a letter too close to the edge of the old fracture, he accidentally broke another fragment of the grenade, creating one of the modern fractures. This incident was repeated a second time. Having learned his lesson, the counterfeiter then took care to move away from the edge of the break. This is the main argument put forward by critics who doubt the age of the inscription. If the counterfeiter took care to move away from the edge of one of the breaks, thus preventing the letter from spilling over into the fracture, then this would be clear evidence of forgery.

More importantly, André Lemaire's examination of partial letters has clearly demonstrated that they overflow into the break. If a letter enters the old fracture, it means that the inscription is authentic, because the inscription was present before the old fracture.

With the help of a state-of-the-art stereoscopic microscope, the committee should now be able to determine whether a letter protrudes into the break, by examining it not only from the front, but also from above and from the side. The question is whether we can identify this characteristic shape of the v in the incision of partial letters 3, 4 and 8, or if a forger has deliberately stopped just short of the edge of a break.

Image opposite: a meeting at the Israel Museum in 2015, from left to right: Robert Deutsch, Ada Yardeni and, from behind, André Lemaire. Biblical Archaeology Review.

Given these conditions

Given these conditions

accepted by all, the committee can

now examine

the three partial letters in question :

Image opposite: in the foreground in front of the microscope:

Aaron Demsky. Then, in the background, from right to left: André Lemaire of EPHEP, Kyle McCarter of Johns Hopkins University, Hershel Shanks, editor of Biblical Archeology Review, © Musée d'Israêl / David Darom.

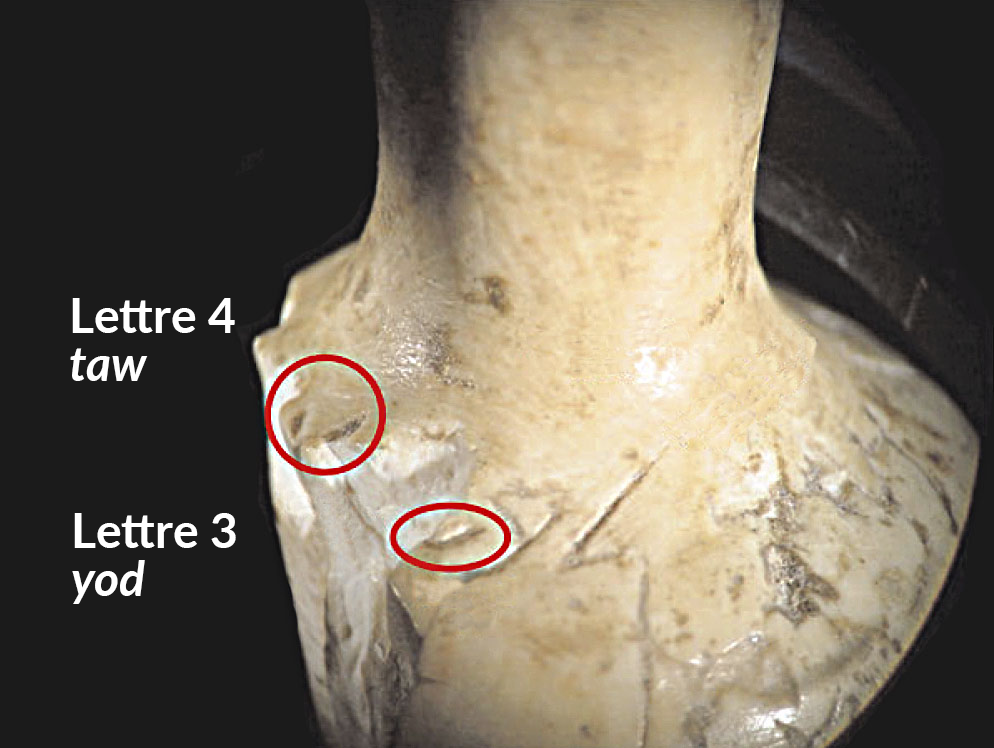

The first letter (letter n°3), a yod or Y

Image opposite: letters 3 and 4.

The microscope is held by Yuval Goren of Tel Aviv University. He is not an epigraphist and will not comment.

The small ivory grenade is then placed under the stereoscopic microscope and analyzed from all angles. The various views are projected onto a screen connected to the microscope, enabling the few other scientists present to analyze them in detail and comment on them together.

It turns out André Lemaire is right. The letter does spill over into the break. Aaron Demsky and Shmuel Ahituv admit their mistake and acknowledge that their previous report was wrong on this point.

View No. 1, taken from the side, clearly shows that the yod overflowed into the fracture.

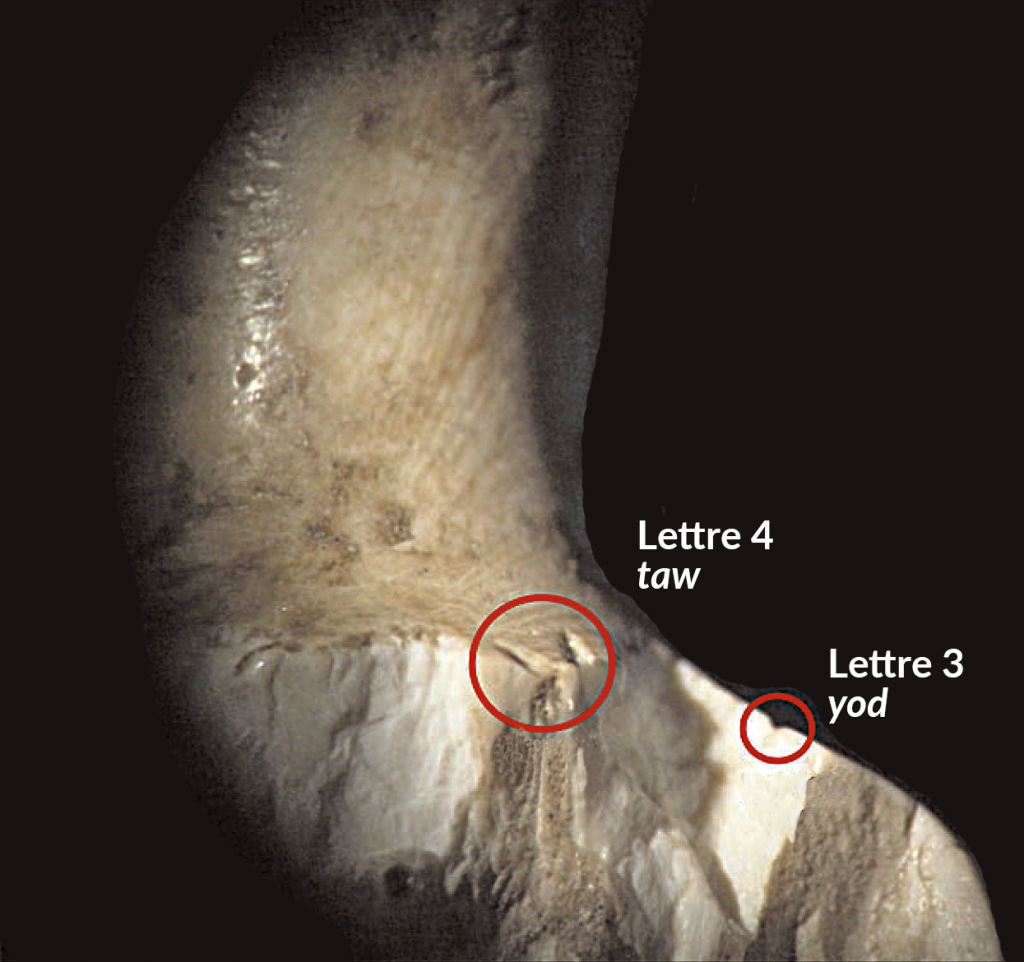

The second letter (letter n°4), a taw which is the letter in the word byt (temple).

Image opposite: letters 4 and 3.

At a new meeting at the Israel Museum in 2015, André Lemaire, Ada Yardeni and Robert Deutsch revisited the inscription, focusing above all on the letter taw. The digital analysis is carried out by digital imaging specialist Bruce Zuckerman, program director of the West Semitic Research Project at the University of Southern California. They agree that this important letter did indeed enter the ancient fracture and conclude that the inscription is authentic.

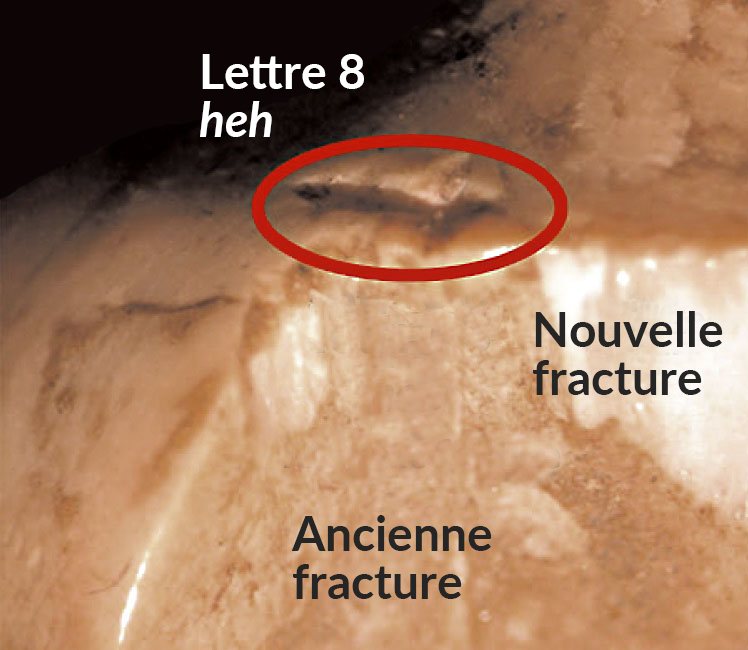

The third and last letter (letter n°8), heh from the name of the Israelite god YHWH

The third and last letter (letter n°8), heh from the name of the Israelite god YHWH

For André Lemaire, the result is obvious. The upper end of the vertical line of the letter goes into the break, forming a « v »in the incision.

A. Demsky and S. Ahituv, however, remain skeptical but do not express their doubts. A vertical line of the heh clearly protrudes into the ancient fracture.

Inexplicably, they did not include the various comments exchanged on this partial letter in their May 3 report.

Image opposite: letter no. 8.

A new hypothesis?

Professor P. Kyle Mc Carter of Johns Hopkins University gave a personal account of view no. 3 at the May 3 expert day. He believes that the projected image may represent the last letter W of the tetragrammaton YHWH. However, he presents his thinking as a hypothesis. He is supported by André Lemaire. Is it possible that a tiny part of the end of this letter, the vov (or wow in school parlance) gone unnoticed? The vertical line of letter no. 8 leads into the fracture and, on the right, the upper end of letter no. 7 seems to be visible.

Text and translation by Professor André Lemaire. Montage Théo Truschel.

Conclusion

The May 3, 2007 meeting, with its new views and the comments of the various scientists present, showed that epigraphers are far from comfortable with the digital images projected by the computer. On the other hand, those using the computer are not epigraphists, although their skills in their respective fields are not in question.

In December 2008, Professor Yitzhak Roman of the Institute for Technology and Forensic Consulting Ltd, following an expert examination of the broken engraving, confirmed the grenade's antiquity, dating it to around 1200 BC, and the authenticity of its inscription.

Later, chemical tests would provide indisputable proof: the hand of a scribe had indeed engraved the pomegranate in the 8th century BC.

Given these conditions

Given these conditions The third and last letter (letter n°8), heh from the name of the Israelite god YHWH

The third and last letter (letter n°8), heh from the name of the Israelite god YHWH