Bible, History, Archaeology

History,

Archaeology

Home >

New Testament manuscripts,

rolls or codices

Image opposite: from papyrus scrolls to the codex, the ancestor of the book. © Grzegorz Zdziarski.

SOME OF THE MAIN MANUSCRIPTS

There are currently around 5674 Greek manuscripts of the New Testament or parts of it, and around 19,300 manuscripts of different versions, making a total of almost 25,000 manuscripts.

Visit papyrii (plural of papyrus)

- The Oxford papyrus (a passage from Matthieu 26 and dated to 50 AD by C. Thiede: date disputed by some specialists).

- Ryland papyrus or P52 (circa 125 AD). This is a double-sided fragment of the Gospel of Jean.

- The papyrii from the Chester Beatty Collection in Dublin. This collection was made public in 1931. It consists of eleven fragments in Hebrew script from nine books of the Old Testament and fragments in Greek from 15 books of the New Testament. The papyrii were written between the 2nd and 4th centuries AD.

- Another important group is the collection of the Fondation Martin Bodmer, made public in Geneva from 1951 to 1962: these 22 papyrii contain passages from Luc, Jean, Epistles of Pierre, Jude, etc. dating from around 200 AD.

On a papyrus fragment discovered in Qumran's Cave 7, verses from the Gospel of Christ are depicted. Marc could have been deciphered (?). This papyrus dates from before 70 A.D. However, this fragment contains only twenty or so letters, of which ten or so we know for sure, hence the controversy...

MANUSCRIPTS IN UNCIAL LETTERS (CAPITALS)

There are around 306 of them, written between the 4th and 9th centuries AD.

The main ones are :

Codex Vaticanus (c. 325 - 350 A.D.)

This is the oldest known Bible, probably written in Egypt in the early 4th century, in the circle of Athanasius, bishop of Alexandria (circa 293-373). This famous manuscript belongs to the Vatican Library founded by Nicholas V in 1448; it was Pius IX who opened it up to scholars. He commissioned the production of excellent facsimiles of the codex Vaticanus, which can be found in major European libraries.

Measuring 27 to 28 cm high and 27 to 28 cm wide, it comprises 759 leaves, 617 of which are for the Old Testament and 142 for the New Testament.

The manuscript is incomplete. The passages from Genesis 1 to 46, the Psalms 105 to 137 and the end of the New Testament from Hebrews 11,14 (where the manuscript stops, in the middle of the word «purify»). All the rest is either missing or of more recent writing. Marc 16,9-20 is omitted. But a blank space is reserved here, showing that the copyist seemed to know the passage. The Sinaiticus also omits it. This is why the passage is enclosed in square brackets in modern editions of the New Testament.

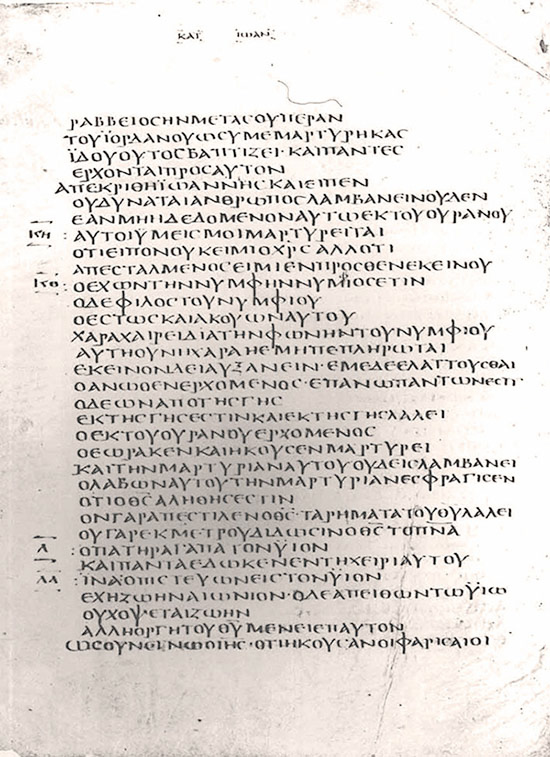

Image opposite: the Codex Vaticanus, the oldest known Bible, probably written in Egypt in the 4th century. Vatican Library. Image montage Théo Truschel.

Unfortunately, a 10th-century copyist, perhaps fearing that the handwriting would fade, crudely ironed it all out with fresh ink. His fear was in vain, for here and there words left as they were, because they were written in duplicate, have remained clear and legible despite the passing of fifteen hundred years.

This manuscript is of prime importance in establishing the Greek text of the Bible. C. Tischendorf suggests that it was copied in the same scriptorium as the codex Sinaiticus. He also believes it to be the work of three different copyists, while the New Testament is entirely the work of a single copyist.

Codex Sinaiticus (circa 350 - 400 AD).

This manuscript is one of the most famous and important of the Greek Bible.

In the spring of 1844, Constantin Tischendorf (a German Protestant theologian) visited the Orthodox monastery of St. Catherine at the foot of Mount Sinai. There he discovered a number of discarded leaflets, acquiring 43 in all. He brought them back and offered them to the Saxon king Frederick Augustus II, who deposited them in the University Library of Leipzig, where they remain to this day. In honor of the sovereign, C. Tischendorf calls these leaves codex Frederico-Augustanus. The term codex Sinaiticus is reserved for the leaves that Tischendorf brought back in 1859.

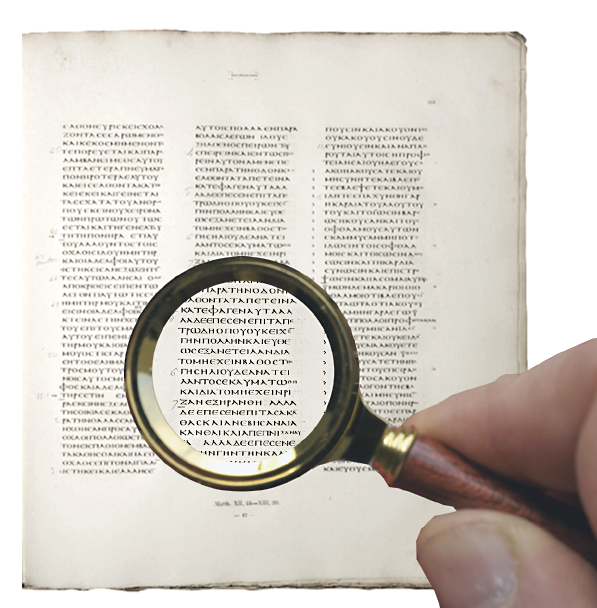

Image opposite: the codex Sinaiticus is a complete manuscript of the New Testament in uncial script.

Today, the Leipzig University Library, the British Library, the Russian National Library in St. Petersburg and the Greek Orthodox monastery of St. Catherine in Sinai each preserve a part of the precious document. Image DR.

On September 28, 1859, the monks of St. Catherine's Monastery authorized him to take the precious manuscript to Europe for study; an edition was immediately undertaken and completed in 1862. But the manuscript never returned to Sinai, a fact that continues to cause problems to this day. On November 10, 1862, C. Tischendorf presented it to Tsar Alexander II of Russia, and seven years later it was deposited in the Imperial Library in St. Petersburg, before being purchased by England through subscription in 1933 and deposited in the British Museum. All 342 precious leaves are now in the British Library in London, with the exception of the 43 leaves recovered by C. Tischendorf during his first visit to St. Catherine's Monastery in 1844. In 1975, a dozen more leaves were discovered at the monastery.

This codex is an extremely fine manuscript, made of antelope skins and written in uncial letters with four columns per page, in a format of 43 x 37 cm. The text contains no accents or spaces between words or phrases. The handwriting is beautiful and easy to read. C. Tischendorf distinguishes four different scribes who may have worked on this manuscript. It contains the New Testament in its entirety, with the exception of the end of chapter 16 of the Gospel of Christ. Marc, from verse 9 to 20. At the end of the New Testament, the Epistle of Barnabas and Hermas' pastor (apocrypha).

The Old Testament, on the other hand, has suffered greatly, with only fragments of chapters 23 to 24 of the Genesis, 5-6-7 of the Numbers, 9 to 19 verse 17 of the first book of the Chronicles, 9 verse 9 at the end of the second book of’Ezra (apocryphal), Nehemiah, Esther, then four apocryphal books: Tobie, Judith, I Maccabees and IV Maccabees, Isaiah, Jérémie, chapters 1 and 2 of the Lamentations, Joël, Abdias, Jonas, Nahum, Habakuk, Sophonie, Haggai, Zacharie, the Psalms, the Proverbs, l’Cleric, the Song of Songs, Job and two apocryphal books: Wisdom, l’Clergyman (or Syracide). Today, according to most specialists, it is the most reliable and oldest New Testament text we possess.

This codex is considered to date from the 4th century. C. Tischendorf has speculated that it may be one of the fifty copies of the Bible that Emperor Constantine asked Eusebius to have executed in 331, but this seems unlikely.

In France, we have a facsimile donated by Alexander II, which is kept at the Société Biblique de Paris.

A view of the Orthodox monastery of Saint Catherine, at the foot of Sinai. C. Tischendorf discovered several leaves of the 4th-century codex Sinaiticus © Marc Truschel.

The Alexandrinus codex (circa 5th century AD)

This is one of the most famous manuscripts of the Greek Bible, and probably the most valuable in Christian biblical history. It belongs to the British Library in London.

This manuscript dates from the 5th century, and there are strong indications that it was copied in Egypt. As early as the end of the 11th century, it belonged to the patriarchal treasury of Alexandria, as we learn from an Arabic inscription at the bottom of the first page of the Livre de la Genesis.

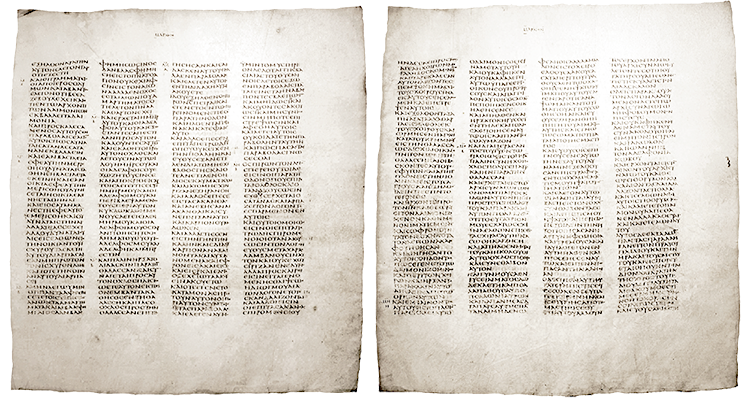

The script is uncial, in a 4th-century hand. The parchment is divided into quires of eight leaves each; each page has two columns of text and each column 49 to 51 lines. Large initials in the margins announce the beginning of each paragraph. No accents, no spaces, just dots for punctuation. Measuring 32 cm high by 26 cm wide, it is divided into four volumes, containing a total of 773 vellum leaves.

Image opposite: two leaves from the Alexandrinus codex. Public domain.

It contains the almost complete text of the Old Testament in Greek, plus the four books of the Maccabees, the Epistle of’Athanase in Marcellin on Psalms and the Apocryphal Psalm 151, the Hypotheses of the Psalms by Eusebius of Caesarea and the canons of the Morning and Evening Psalms.

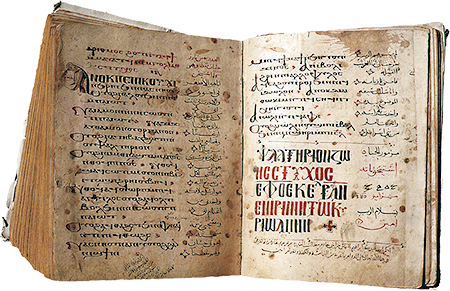

Image opposite: The last two pages of the apocryphal Psalm 151, dedicated to David's fight against Goliath:

[...] I went to confront the Philistine. He cursed me with his idols. But I tore off his sword, beheaded him and washed the children of Israel clean. Twelfth-century manuscript in Coptic and Arabic.

Coptic Patriarchate Library. Theo Truschel.

The New Testament also contains, at the end and in the same handwriting, the text of the First and Second Epistles of the Apostles. Clément (extra-canonical), bishop of Rome. An early table of contents, added to the work, indicates that the Second Epistle of Clément is followed by Psalms of Solomon, which complete the volume. The missing passages are Matthieu 25,6 ; Jean 6,50 ; 8,50 ; 2 Corinthians 4,13 ; 12,2.

The Bezae and Claromontanus codices (6th century AD)

The codex Bezae Cantabrigensis

Along with the four great uncials - the codices Alexandrinus, Vaticanus, Ephraemi rescriptus and Sinaiticus - this codex is an essential scriptural witness to the Greek New Testament.

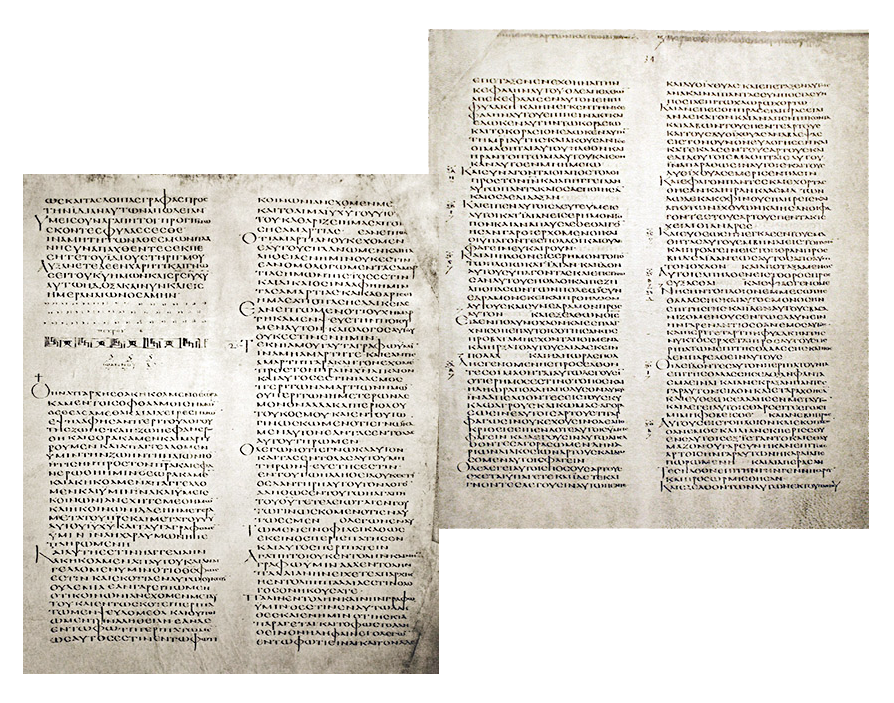

Image opposite: the Bezae codex. This is a bilingual manuscript, Greek and Latin, written in uncial script on vellum, containing the Gospels in their own order, which it shares with the codex Washingtonianus or Freer codex.

It was donated to Cambridge University by Theodore de Bèze (circa 1581), who received it in Lyon, where it was found in the Saint-Irénée monastery in 1562. It is dated to the end of the 5th century. It owes its name to Théodore de Bèze, one of the great Reformers.

It's a bilingual manuscript, Greek and Latin, written in uncial script on vellum, containing the Gospels in an order of their own, which it shares with the codex Washingtonianus or Freer codex: after Matthew comes John, then Luke (the only complete one) and Mark; after a gap of 67 folio, the manuscript resumes with the Third Epistle of John and, finally, the Acts of the Apostles up to chapter 21. It comprises 406 folios (the original may have had 534). Each of the marks of the nine correctors who worked on this manuscript between the 6th and 12th centuries has been identified and catalogued by F. H. A. Scrivener, who edited the text (in cursive) in 1864.

The Claromontanus Codex

Named by Theodore de Bèze, who bought it from a monastery at Clermont-en-Beauvaisis in the Oise region of France, the Epistles of Paul is a 6th-century manuscript in Greek and Latin. It contains the Epistles of Paul and is kept at the Bibliothèque nationale de France. It comprises 533 folios (24.5 x 19.5 cm).

It also includes a stichometric catalog 1 of the Old and New Testaments.

Together with the Codex Augiensis and the Codex Boernerianus, the text of the codex represents the western type of Paul's Epistles. The main feature of this corpus is the absence of the Epistle to the Hebrews, which is appended after the stichometric table. The order of the 13 epistles is: Romans, 1-2 Corinthians, Galatians, Ephesians, Colossians, Philippians, 1-2 Thessalonians, 1-2 Timothy, Titus, Philemon.

1. A stichometric catalog is a table that gives the number of stiques (= lines) for each text in a book. It is a technique used by ancient scribes to check the completeness of a work.

The Ephraemi codex (5th century AD).

It's a palimpsest 1 which was «scraped» in the 12th century to accommodate the writings of Father Ephrem, hence its name.

This is a vellum manuscript of the Old and New Testaments in uncial Greek script. Only part of the original manuscript has survived. It includes portions of all the New Testament books, with the exception of the Second Epistle to the Thessalonians and the Second Epistle of John, amounting to 145 leaves, and 64 leaves for the Old Testament. Written in Asia Minor, it was brought to Florence after the fall of Constantinople, and taken to France by Catherine de Medici.

This text is thought to date from the first half of the 5th century. C. Tischendorf uncovered the primitive text with the help of chemicals. Today, this manuscript can be found in the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

1. Derived from the Greek palin («again») and psestos («scraped»), i.e. a manuscript that has been «scraped» to be used for other purposes; it originally contained the entire Bible.

MANUSCRIPTS IN CURSIVE (LOWER-CASE) LETTERS

There are around 2,856 of them, written between the 9th and 15th centuries AD.

ANCIENT TRANSLATIONS OF THE NEW TESTAMENT

There are over 15,000 of them (including over 8,000 from the Vulgate in Latin, and around 8,000 in Ethiopian, Slavonic and Armenian). In Syriac (Codex Syro-Sinaïticus, Codex Syro-Curetonianus of around 200, ... ), Latin (Codex Bobiensis of around 400, Codex Vercellensis of around 360, ...), Gueze (ancient Ethiopian), Coptic, Arabic, etc., the Vulgate is available in a variety of languages.

- Biblical quotations from the Church Fathers

- Lectionaries

We own around 2403 of them.

These are collections of biblical texts used for religious services. Most date from the 7th to 12th centuries, with a few fragments from the 4th, 5th and 6th centuries.