Bible, History, Archaeology

History,

Archaeology

Home >

Massada, the position From Hasmoneans to Herod I the Great, from 138 to 4 BC.

Contents:

A fortress built in the middle of the desert, Masada has a history that captures the imagination and the conscience. In this first section, we'll look at the site's importance during the period of Hasmonean independence and the long reign of King Herod the Great.

An aerial view of Masada

The cliffs on the east side are around 450 metres high; on the west, around 100 metres high. Here you can see the ramp used by the Romans to gain access to the site after a long siege. Frachtenberg.

Introduction

Massada is already an incredible natural site. A vast rock suspended between heaven and earth, from its heights you can dominate the entire region in a single glance. Rising almost 400 metres above ground level on its eastern flank and more than 100 metres to the west, the plateau, carved out by time like a vast table with a rhomboidal outline, stretches 600 metres from north to south and 300 metres from east to west. This plateau, swept by winds from the Judean desert towards the Dead Sea and the land of Moab, has survived in a particularly hostile environment, as there is no water. It took all the ingenuity and folly of men to bring water to this isolated site, in order to build a fortress and a palace.

The only ancient author to have left us long descriptions of the site through the centuries is Flavius Josephus. In the absence of any real choice, he will be our guide. We'll be supported by archaeology and the resounding work of Yigael Yadin, who pioneered exploration of the site from 1963 to 1965.

Masada and the Hasmoneans, 168-37 B.C.

Masada is also the paradigm of a complex history, witnessing the major stages of the Jewish kingdom during the nearly three centuries that shook the region from the Hasmoneans to the Romans (from 168BC to 73/74BC).

Historians and archaeologists can trace the earliest occupation of the site back to the Hasmonean period, when the Seleucid armies forbidding Jewish worship clashed with those obeying a Jewish family, Matthatias and his sons, firmly resolved to oppose the edict of persecution and religious bans. Religious war? Let's not be anachronistic. War of independence? In a way, at any rate, this struggle saw the rebirth of a Jewish state over several generations, conveniently referred to as the Hasmoneans. This state was organized and supported by a network of forts and fortresses.

The question remains as to who first built a fortress on this desolate plateau. Flavius Josephus mentions a certain Jonathan. Was this Jonathan, the brother of Judas, nicknamed Maccabaeus, who took power in 160 BC, and of whom Flavius Josephus claimed direct descent? But why are the texts silent on the control of this area by his troops? Flavius Josephus situates his military action much further north, in the vicinity of Jerusalem or at Tekoa, south of Bethlehem. It should be noted, however, that Jonathan Maccabaeus, in the midst of his war with the Seleucids, heirs to Alexander the Great, renewed his treaty of alliance and friendship with Rome, the rising power in the East at the time, in 143 BC. In the eyes of the historian, it opened the door to further Roman action in the region, which would see the annexation of Judea to their Empire.

Other researchers identify the Jonathan cited by Flavius Josephus as Alexander Jannaeus, a distant descendant of the Maccabean family, whose Hebrew name was Jonathan. Coins minted in his time and found on the Masada plateau or a document unearthed at Qumran explicitly refer to him by his Jewish name. His long warrior reign (103-73 BC) enabled him to significantly expand the Jewish kingdom and take control of the region south of Masada. In this way, the citadel probably functioned as one of the locks of the southern Jewish frontier. To the south, in the Negev, the Nabataeans disappeared. The roads linking Petra to Gaza seem to have been cut off from them by Alexander Jannaeus. They would not be able to return until Herod's reign, probably with his agreement, in return for taxes on the spice market trade from Arabia, a source of immense revenue.

Masada and Herod I the Great, 37-4 B.C.

The second phase of site occupation corresponds to the Herod's reign (- 37 à - 4). A brief historical parenthesis is necessary to understand Herod's visit to this site.

On the death of Alexander Jannaeus in 73BC, the vast Hasmonean kingdom, entrusted to his young widow Salome, broke out in 67BC under the pressure of the rivalry between the two sons, Hyrcanus and Aristobulus. It was precisely at this time that Pompey, the Roman general-in-chief, who was in the East to hunt pirates, was approached by the protagonists and intervened as arbitrator in the fraternal conflict. He took Jerusalem in autumn 63 and entrusted power to Hyrcanus, who was advised in this choice by Antipater the Idumean, Herod's father. Judea falls under Rome's control.

From the murder of Antipater (in 43BC), a victim of the bloody conspiracies that plagued both branches of the the Hasmonean family, Six long and terrible years passed between the birth of the kingdom of Judea and its takeover by the unknown Herod, marked by the seal of death. Herod, in those indecisive years, passed Massada several times. Once, to avenge his father's murder, he laid siege to the citadel and finally took it, even though it was already considered the best defended in Judea. Another time, when he fled from Antigone, son of Aristobulus, who had sworn his death. In his desperate flight, he thought he'd lost his mother at the future site of the Herodium, tried to kill himself, but finally overcame the pursuing enemy army and took refuge in Masada with all his troops. It was there that he left some of his family, his mother, his sister and his fiancée, while he went to Rome and obtained the legitimacy of the Roman Senate. He would not forget this effective refuge.

In 37BC, Herod became king at the cost of immense losses and deep traumas that haunted him. He built an incredibly ingenious site in the hills southeast of Jerusalem to commemorate his victory over Antigone, it was the Herodium where he was buried. As for Masada, which had been a safe place for him and his family, he modernized it to make it not only a better-guarded fortress, but also a luxurious palace with baths.... in the middle of the desert!

It's this miracle of the already highly sophisticated technique of ancient engineers that we're now going to examine.

Masada, the desert fortress

The appearance of ancient Masada was that of a fortress built on a rocky outcrop with vertiginous slopes. Surrounded by a double wall, six meters high according to Flavius Josephus, and protected by 37 towers, 25 meters high, Masada was pierced by four gates. Two of these led to the network of water cisterns built into the hillside. Two others led outside the site. The Serpent track to the east, which zigzagged over the 300/400-meter-high cliff, and the western track, largely covered by Roman earthworks in +73/74, designed to capture the Jewish city. The western flank, with its gentler gradient, was the site's weakest point. It was on this side, of course, that Rome's troops would attack a century after the construction work was completed. And it wasn't the tower built by Herod on the west side, 500 metres from the summit, that was able to stop their momentum for long.

The cliffs on the east side, overlooking the Dead Sea, are some 450 meters high; on the west, they dominate the valley by around 100 meters. Pedestrian access to the site is difficult. It is a mesa, a virtually flat plateau extending over some 15 hectares, flanked by steep cliffs. It is shaped like a triangle, approximately 600 by 300 meters. © Boris Diakovsky. 68509717.

Masada and water

But this desert fortress would have been an empty shell of little military interest were it not for an extensive water supply and storage system. We had to rely on much more than the rare winter rains to keep Masada alive. And even if Herod, not yet king when he fled from Antigone, had witnessed the miracle of an unexpected thunderstorm that filled the fort's water reservoirs, he apparently hadn't forgotten that the site could only really be defended if the rainwater conveyance system was rethought.

He had several series of rock-cut cisterns built on the side of the plateau, 80 and 130 meters from the summit, with a total capacity of 36,000 cubic meters. They were fed by an ingenious system of dams, canals and aqueducts, allowing the reservoirs to be filled by the sudden winter rises of water from the nearby nahals (ravines or canyons). There were then two paths leading from the cisterns to the summit. Donkeys must certainly have used these paths, climbing the steep slope to pour their precious cargo into a clever network of canals leading to the various reservoirs scattered across the vast plateau. From time to time, during the winter, as in Herod's memorable episode, these reservoirs must have benefited directly from the gift of heaven. Thus, after careful calculations, between 10 and 15,000 cubic meters of water could be stored on the plateau and accessed directly. That made a total of over 30 million liters available on the plateau!

Massada and its virtuous villa

Herod wanted to turn this fortified site into a place for vacation and relaxation. He built sumptuous monuments. Was he inspired by the writings of his contemporary Vitruvius? In any case, the buildings that are still standing despite the ravages of time bear witness to a luxury and technique that archaeologists are finding in Pompeii. What a benchmark! In the space of almost 20 years, from 30 BC to 10 BC, the face of the plateau changed.

Herod and his team of architects, clearly influenced by the Roman and Greek schools, designed a villa built on the edge of the void. Taking advantage of the uneven terrain to the north of the site, the engineers boldly embarked on a disproportionate project, building a monument on three levels corresponding to each fracture in the plateau and linked by a staircase running along the wall. As the only part of the plateau less exposed to the scorching sun and spared from the violent southerly winds, it took all the ingenuity and skill of the architects of the day to build a haven of peace overlooking the sea and desert. Neither time, war nor earthquakes have dented the foundations of this sumptuous villa, which can still be visited today.

Image opposite: magnificent mosaics, among the oldest in Israel. danah79.

On the intermediate floor, 20 meters below, a vast circular building was designed, the foundations and a few capitals of which have survived. Again, this must have been a Hellenistic-style tholos building with colonnades, open to the north. On the other side of the floor, on the south side, based on clues left in the wall, some researchers have proposed the reconstruction of a library.

The top floor, 15 metres below, was accessed via a staircase invisible from the outside. The most tapered part of the promontory, this level corresponded to a vast artificial platform resting on retaining walls up to 25 metres high! In the center, a courtyard richly decorated with panels imitating the various marbles. To the east, Herod built private baths overlooking a 300-metre drop in elevation.

The whole edifice demonstrates King Herod's delusions of grandeur. But that's not all!

Masada and the baths

In the middle of the desert, in a fortress built at the top of an eagle's nest, can we imagine a thermal bath whose construction technique is as advanced as that of Italy? The decoration, the construction technique, the proximity of the building and its location on the same axis as the northern villa make it a very important building at Masada. Organized around the traditional five rooms - palaestra (peristyle), apodyterium (checkroom), tepidarium (warm room), frigidarium (cold room), caldarium (warm room) - water was supplied by an ingenious network of pipes connected to cisterns. Herod was so fond of this type of construction that he installed it in his various palaces in Jericho, Cypros and Herodium. Archaeologists have even been able to observe that their construction technique is still Roman, following to the letter the instructions of Vitruvius, who recommended for the caldarium a slightly sloping floor towards the boiler, with tiles for the walls and pillars for the double floor of the hypocaust in strictly predefined formats.

It was precisely during this period that the construction of public baths was at its height in Italy, and in Rome in particular. As the Roman day ended around midday, he went to the baths to wash, shave, sweat and get a massage to relax and look more beautiful. It was also an eminently social place for chatting, doing business and networking. Herod picked up on the fashion of the moment in Rome and realized that time spent in the baths could prolong his health. Covered in perfumed oil, after passing through the tepidarium, the ancient man could perspire and eliminate filth by going to the caldarium, where the temperature rose to 40° degrees. Here, he could accelerate the sweating process by drinking. Then, once he'd worn himself out from the heat, he'd head back to the tepidarium to be massaged by a slave and smeared with ointment, before taking refuge in the frigidarium, where his skin would firm up under the effect of the cold. More than a moment of relaxation and leisure, the thermal baths were part of a way of life.

Herod's grandiose constructions in Judea demonstrated the importance he attached to living the Roman way of life, having spent many years in the Urbs. This lifestyle also applied to the arts of the table.

Masada and the pleasures of the table

It's hard to believe that this fortress housed vast warehouses filled with precious commodities. Archaeologists were amazed to discover old amphorae of ancient wine in these stores, each weighing between 200 and 250 kg and rising to heights of over three metres. But not just any wine! Famous wine from Spain, Greece and Italy! Vintage wines from the Brindisi region and Campania, Anineum, praised as far back as the time of Cato the Elder (late 3rd, early 2nd century BC) and Tarantinuum, but also Massicum excellens. These amphorae are dated and some bear the royal title Regi Herodi Judaico. Just over half a century after Herod placed this order, the first list known to historians of classified crus is found in the work of Pliny. Many of those found on Masada are among the most sought-after. Clearly, there was no question of drinking anything just because you were in the middle of the desert.

But it wasn't all wine at the kings' table. Apples from Cumae and Spanish garum (a fish sauce, a staple of Roman cuisine) were found in the warehouses. Also discovered were jars bearing descriptions in Hebrew of a wide variety of contents: fish, meat, dried figs, almonds, apricots and even the now extinct balsam that was found along the Dead Sea, particularly at Ein Gedi, a few kilometers away.

In short, these warehouses once again testified to the extreme attention to detail and quality of life that could be achieved over 300 meters above ground in the middle of the desert. Nothing was to be overlooked and everything had to be done to forget the constraints of the place, even though this luxury had always been skilfully guarded by all manner of defensive edifices. A tower dominated the southern end of the shopping complex. A wall separated the three-storey villa from the rest of the neighboring buildings, i.e. the public baths and warehouses. For even if Herod wanted to forget the site's primary function with this profusion of resources, it was first and foremost a citadel that had to be ready to withstand a siege or worse, an assault.

Masada and the palace

If you step away from the building-rich northern part of the site for a moment, you'll be drawn to an architectural complex that dominates the plateau to the west, and which archaeologists have conveniently dubbed the «Western Palace». Built on the highest part of the plateau, it offers a view of almost the entire site. For Herod, at Masada, as at many other sites, when he built a solid fortress, did not intend to sacrifice places of relaxation and pleasure, but naturally also created a space reserved for the exercise of his power. This building is precisely that place of power, surrounded by five other, smaller edifices built along the same lines as the previous one. These were probably intended to house members of the court.

Left: remains of a colombarium at Masada. Niches for «pigeons» where, according to some historians, funerary ashes were stored. David Shankbone.

Left: remains of a colombarium at Masada. Niches for «pigeons» where, according to some historians, funerary ashes were stored. David Shankbone.

The West-East Palace is the largest and most sumptuous building at Masada. It covers an area of almost 4,000 square meters. Its decoration and spatial organization correspond to the best that the architects and craftsmen of the time could offer. Without going into details that would take us too far (see bibliography at the end of the third article), let's simply note that the succession of spaces, organized around landscaped courtyards, is typically Hellenistic and corresponds to what could be found in other palaces of Herod and the great houses of the period in Greece and the Orient. In this immense building were found warehouses, a whole wing reserved for the running of the palace - a service wing - again baths, superb mosaics, among the oldest in Israel, and of course, a room where power must have been exercised, called the throne room. The palace had at least one other floor, since staircases have been found that would have given onto a rather striking view of the Judean desert.

Herod's huge building site at Masada was clearly part of a vast architectural policy on the part of the royalty, who wanted the very best for themselves. These gigantic construction sites, described by Flavius Josephus and rediscovered by modern archaeologists, shed new light on ancient architectural techniques and their distribution in the East. They also speak volumes about the man who initiated these projects, and his ambitions).

Conclusion

Herod's rapid inventory of the buildings on the Masada plateau does little to conceal the historian's unease when it comes to explaining what King Herod wanted to do there.

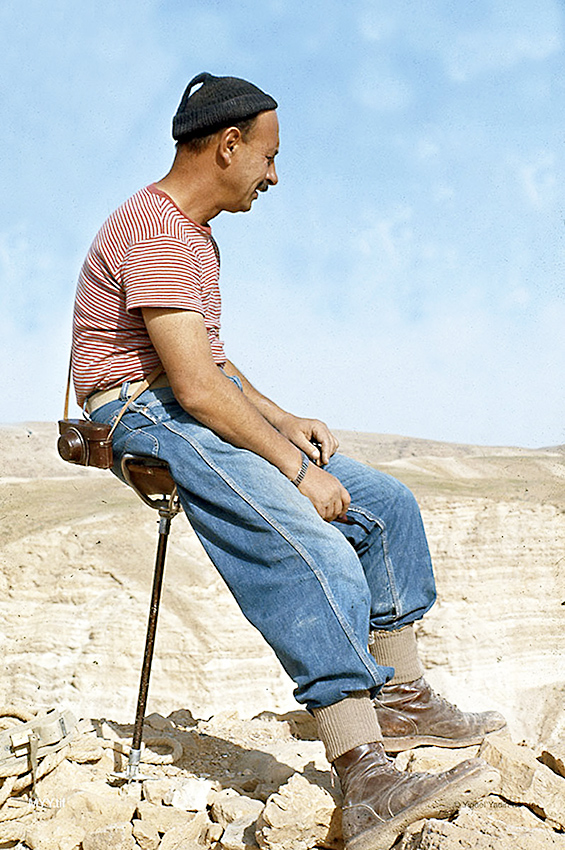

Image opposite: Yigaël Yadin (1917-1984), archaeologist, politician and high-ranking military officer in Israel. He was the son of the great researcher Eleazar Sukenik © Image Archaelogical Photographs Yadin's Productions.

But why do we get the feeling, from reading Flavius Josephus or excavation reports, that Herod's aim was less to build strong points as part of a strategic defensive line against external enemies than to construct enclosed spaces to protect himself from internal enemies? Flavius Josephus, echoing the work of Nicholas of Damascus, Herod's historian and biographer, states that the reason for building Masada was primarily to protect himself from his own people (Jewish Antiques XIV, 354), but perhaps also from the cruel Egyptian Cleopatra, protected for a time by Mark Antony, who never stopped trying to kill him in order to take over his kingdom. As we know from Flavius Josephus and other ancient authors, Herod's life was tormented, his enemies were legion and suspicion seems to have dominated his reign. It's not easy to overthrow a dynasty - the Hasmoneans - that had been in power for over a century, even with Roman support. These palace-fortresses, of which Masada is the most emblematic, bear witness to an era of tension, when architectural genius was at the service of the whims of the powerful of the moment. It is this antagonism between the political turmoil and power of the time that attracted so many historians to revive a history of Herod based on the writings of Flavius Josephus. And in the recent writing of this story, Masada plays an eminently paradigmatic role, even if Herod seems to have spent little time on this desolate but well-appointed plateau.

Find out more

Mireille Hadas-Lebel, Rome, Judea and the Jews

Collection Antiquité/Synthèses.

Éditions Picard, 2009.

Left: remains of a colombarium at Masada. Niches for «pigeons» where, according to some historians, funerary ashes were stored. David Shankbone.

Left: remains of a colombarium at Masada. Niches for «pigeons» where, according to some historians, funerary ashes were stored. David Shankbone.