Bible, History, Archaeology

Bible,

History,

Archaeology

Marine archaeology in Israel

Underwater excavations reveal a past preserved by the sea

Underwater excavations in northern Israel reveal a past preserved by the sea.

While much of Israel's soil has already been the subject of major archaeological excavations, the seabed is just beginning to be explored.

barely to reveal their treasures.

A view of one of Israel's most beautiful Mediterranean coasts (detail): Dor Beach, south of Haifa, which is the focus of major marine excavations. DR.

Introduction

The hum of the powerful underwater vacuum breaks the silence of one of Israel's most picturesque spots, the peaceful Dor Beach lagoon, in the middle of which small islands of sand emerge from the clear waters of the Mediterranean.

Just two meters below the surface, a dozen archaeologists, students and volunteers in diving suits are working like ants, scrupulously combing the sandy expanses with an underwater dredger. This sort of giant vacuum cleaner enables them to delicately unearth fragments of pottery and wood from a ship that sank here over 3,000 years ago.

«After 120-130 years of scientific archaeology on land, we know a lot about what happened on land, but very little about what's on the seabed», explains Professor Assaf Yasur-Landau, Director of the Leon Recanati Institute of Maritime Studies at the University of Haifa.

Image opposite: Students and members of the University of Haifa use sand dredgers to remove up to two meters of sand or dig around treasures buried in the sand of Dor Beach, in May 2023. © Department of Maritime Civilization/University of Haifa.

The School of Archaeology and Maritime Cultures at the University of Haifa is Israel's only qualification program in underwater archaeology. Since 2012, an English version has been offered to foreign students, some 20 of whom will graduate this summer.

«Everything we dig up gives us an enormous amount of information, enthuses Yasur-Landau. «Each ship is a kind of time capsule, giving us an insight into the goods that were traded, the trading relationships that existed and what the environment was like at the time.»

In May, Yasur-Landau supervised the first excavations of two shipwrecks stranded in the Dor Beach lagoon: one from the Persian period, approximately 550 BC, and the other from the Iron Age, 1,000 BC. During the three-week dig, the team discovered ceramic fragments dating back some 3,000 years and tried to determine whether the site had once been a port," explains Yasur-Landau. In autumn, they will resume the excavation campaign for a further three weeks, to explore the seabed even further.

Israel has always been a strategic location for maritime activities, from the first Mediterranean fishing villages (in 10,000 BC) to Roman ports such as Caesarea, to ships loaded with Jewish refugees attempting to circumvent the British blockade after the Second World War.

Excavating objects or ships that sank at sea thousands of years ago is much more complex than excavating on land. It's also much more expensive, requiring boats, sand dredgers, diving equipment and a highly qualified team with specific skills.

Basically, the archaeological procedure is the same - meticulous documentation and excavation, layer by layer - but it's all done underwater, wearing a cumbersome wetsuit, battling currents, waves and tides, not to mention curious fish and tiny jellyfish.

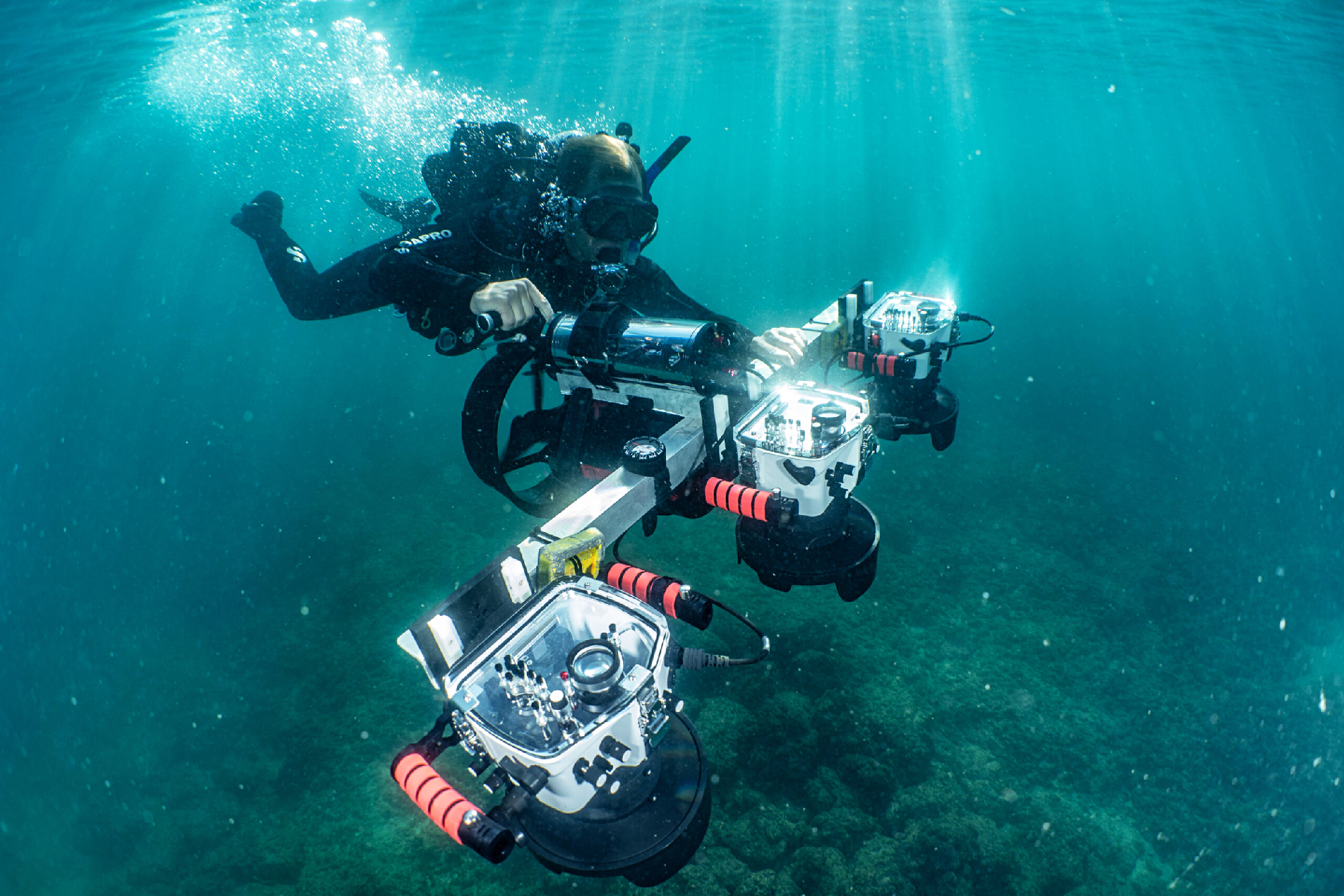

Recent technological advances - such as underwater photography, which can model the seabed in 3D for study on land - have made underwater excavations much easier.

Three-camera photogrammetry platform used to document underwater archaeology in Haifa Bay, Israel. © Amir Yurman, RIMS, University of Haifa.

Under the sea, a doormat is eternal

«Our main objective is to understand the lives of people who have gone before us, how they evolved and adapted, economically, socially or culturally, to a changing environment. »explains Yasur-Landau. «Why are we interested? Because we see processes that began a long time ago, but are still going on today.»

The damage inflicted by human activities on coastal ecosystems, rising sea levels, overpopulation, political difficulties that generate economic problems are all issues that the inhabitants of Israel's coastal region have been facing for thousands of years, and are still facing today, he adds. Maritime trade still accounts for over 90 % of Israel's imports.

«In these seabeds, we have a glimpse of the last 11,000 years, from the time humans began to settle in villages until yesterday», he explains. «We're able to tell what those 11,000 years were like, just by the way people lived by the sea and interacted with it.»

The University of Haifa's program alternates between underwater and coastal land excavations, as coastal villages and ports are very closely linked to the sea. What's more, due to fluctuations in sea level over time, some areas are now submerged, whereas they were once dry land, sometimes the cradle of coastal villages.

The underwater environment is tough, but it's unrivalled in preserving things that would have disappeared on dry land, such as organic materials like wood, rope and straw mats.

Sand creates an anaerobic environment: what is covered by sand is almost completely - if not totally - deprived of oxygen. Yet it is exposure to oxygen that causes organic matter to break down and decompose. Placed in an anaerobic environment, they remain intact much longer.

Yasur-Landau found pieces of straw mats dating from Byzantine times, as well as basketry and twin strings dating from around 300-600 CE. Such objects are rarely found on land, yet they provide invaluable information on what daily life might have been like for our ancestors.

The other advantage of underwater archaeological digs - usually buried under a meter of sand or more - is that they have rarely been visited by the hand of man, unlike Israel's thousands of land-based archaeological sites, which are often looted.

An underwater view, taken by photographer Antonio Busiello, of the ancient city of Baiae (today Baïes, detail) submerged during a volcanic eruption, off the Gulf of Naples. Antonio Busiello.

Praying to Poseidon

Students interested in studying underwater archaeology should ideally have basic scuba diving skills, but Yasur-Landau assures us that it is not looking for highly qualified frogmen profiles. Most underwater excavation sites are shallow, like Dor Beach, which lies between 2 and 4 meters below the surface. It's much more important to be able to work carefully and patiently in difficult underwater conditions," he adds. To start with, you have to like the water.

Underwater excavations can be tedious, involving hours of conscientious sand-sucking to unearth small fragments of wood or ceramics, but for Runjajić they are the most interesting digs of the year.

[…] «We end up having very little time for field work during the year - due to research work, grants or finances - and these are always very special moments.», Runjajić assures us. «The best moment is when we take to the water, because we've been waiting for it for a long time, it's been planned for a long time. All we can do now is pray to Poseidon that everything goes well.

Super vacuum cleaners

Dor Beach has the air of a Caribbean resort, even though it's located on Israel's Mediterranean coast. Three small islands adorn this shallow lagoon, whose bright blue waters reflect a cerulean sky. You couldn't be farther from the rougher parts of the Israeli coast or the grimy port of Haifa, yet only 30 kilometers to the north. These calm, welcoming waters make it easy to understand why sailors of ancient times made this a port thousands of years ago.

Since the 1980s, archaeologists have identified some 26 shipwrecks or cargo remains. Until very recently, it was difficult to excavate the lagoon, as most archaeological remains lie under two metres of sand. In other places on the Carmel coast, archaeological remains have been found under just one metre of sand.

To remove these two meters of sand underwater, teams of ten divers each use two sand dredgers, which suck up sand from one area and spit it out in another. The natural movement of water means that any excavated area tends to refill with sand, so the dredges are constantly active. Archaeologists also use sandbags to prop up the sides of an excavated area, which must extend to at least 10 square meters in order to sufficiently empty the area under investigation of sand.

During the night, the carefully excavated area is once again covered with sand, and in the morning, the archaeologists start all over again.

Yasur-Landau explains that the sandy areas of Dor Beach are not home to a rich underwater fauna, so the excavations have little negative impact on the environment.

Image opposite: an archaeologist explores the cargo of a Phoenician ship wrecked between 1000 and 500 BC, at Dor Beach, during the May 2023 excavation campaign. © Department of Maritime Civilization/University of Haifa.

During a three-week dig campaign in May, the team excavated two sites to explore Persian and Iron Age cargo and shipwreck remains. This was the first time these remains had been excavated since they were identified in the 1990s by Israeli and American divers.

The divers are also on the lookout for pre-Iron Age remains. Yasur-Landau explains that, once they have reached the seabed sediments beneath the sand, they will be looking for traces of human activity dating back to the Neolithic (9,5000 to 4,500 years BC) or even the Paleolithic (more than 9,500 years BC).

In this case, divers will have to use more traditional archaeological tools, such as trowels, to carefully dig into the clay sediments beneath the sand.

Confident, Yasur-Landau is convinced that they will come across remains from this period. In fact, he has invited a number of Neolithic experts to come and snorkel over the excavated area to identify patterns, evidence of some form of human activity.

Remains of coastal Neolithic villages have been found at Atlit Yam, dating from around 8,000 BC: sea levels were much lower then than today, so the village was closer to the water. Underwater archaeology in Australia has also yielded evidence of human settlement along the continent's coastline and underwater, 60,000 years ago.

Silver drachma with the Aramaic-stamped word «Yehud» (Judea).

She « would be the first Jewish play and the first play in the province of Judea. »

Israel Museum, Jerusalem.