Bible, History, Archaeology

History,

Archaeology

Home >

The Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem

The Dome of the Rock, sometimes erroneously called the Mosque of Omar, is a shrine erected by order of the Caliph Abd al-Malik ben Marwan in Jerusalem, on the esplanade of King Herod's former Temple.

Completed around 691 or in the second half of 692 CE, it is one of Islam's oldest monuments.

It is also Islam's third holiest site after Mecca and Medina.

Introduction

As noted on one of the Arabic inscriptions throughout the building, the Dome of the Rock or Dome of the Rock (Arabic: قبة الصخرة, Qubbat Aṣ-Ṣakhrah) was built in the year 72 of the hegira (Arabic: هجرة, hijra, «emigration», «exile», «rupture», «separation»), i.e. around 691, or rather 692 CE, under Umayyad rule by Caliph Abd al-Malik.

Image opposite: a view of the Dome of the Rock on the Esplanade of the Mosques. Public domain.

The latter, at odds with Medina, was well aware that Jerusalem was a pilgrimage destination for both Jews and Christians, and wanted to assert the importance of this site alongside Mecca and Medina, to which Muslims flocked to obey the prescriptions of the Koran. To attract pilgrims to Jerusalem, a territory he tightly controlled from Damascus, Abd al-Malik wanted to turn Islam's third holiest site into a powerful economic and religious magnet, bringing together the three great religions of the Book (the Bible and the Koran).

To achieve this, he needed a center of considerable influence. Abd al-Malik's decision was therefore to erect a monument of representative and exceptional brilliance on the very site that, according to the Bible, the Jews call Mount Moriah in commemoration of Abraham's sacrifice of Isaac (the Binding of Isaac), a patriarch regarded as the common ancestor of Jews and Arabs, and as a sign of supremacy over Christians and Jews.

The Dome of the Rock stands at the center of the Temple Mount - once the site of Solomon's Temple, but destroyed and looted during the siege of Jerusalem in 586 BC. A second Temple was rebuilt between 538 and 417 BC. - which was then considerably enlarged under the reign of Herod the Great, King of Judea, in the 1st century B.C. © Kanuman 789501574.

Mosque Esplanade or Temple Mount?

This site, the immense temenos (sacred space in ancient cultures) of the Haram al-Sharif, is also the esplanade of Jerusalem's ancient Temple - known to the Jews as the Temple Mount - whose the first version was erected by King Solomon in the 10th century BC. and destroyed by the Neobabylonians under Nebuchadnezzar II (the Nebuchadnezzar of the Bible) in 586 BC. A second Temple was rebuilt in the 6th century B.C. on the return of the Judean people from the Babylonian exile, and finally a third version, benefiting from a major renovation, by the Judean king Herod the Great, around 19 B.C. and completed a few years before its final destruction by Titus' Roman legions in 70 A.D.

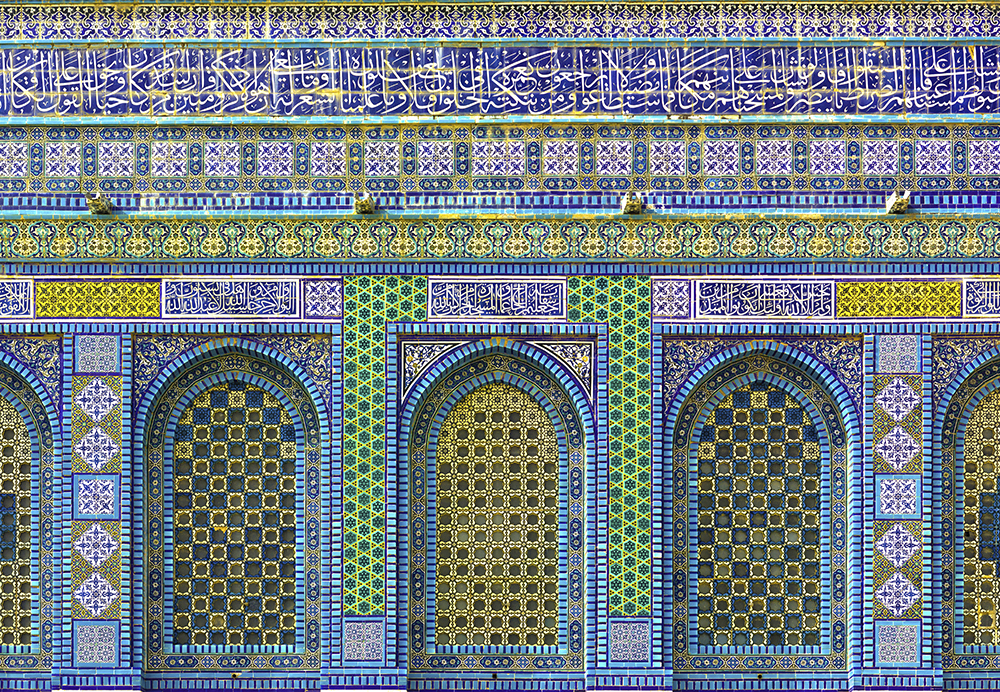

Image opposite: detail of the magnificent colored marble decoration on the exterior façade of the Duomo.

It was on the orders of Suleyman I the Magnificent that the original façade was completely replaced by this Ottoman-influenced ceramic tile cladding. Image and editing by Théo Truschel.

The site had been abandoned after the victory of Christianity under the Roman emperor Constantine.

General view of the Kotel (Wailing Wall), one of the few remaining vestiges of the retaining wall of Herod's Temple, surmounted by the Temple Mount (or Esplanade of the Mosques in Islam) with the Dome of the Rock (left) and Al-Aqsa Mosque (right).. © Sheepdog85.

The story of its construction

The location is all the more appropriate as it would be the setting for the famous miraj or Night Journey, in which the prophet Mohammed, riding his horse Bourak is said to have ascended to the heavens. Islamic tradition has it that the archangel Gabriel led the Prophet, as recorded in the Koran (Sura XVII, chapter on «written text» in the Koran), the Sacred Mosque from Mecca to Mosque far away of Jerusalem. And it is from the sacred rock that Mohammed is said to have ascended into heaven (the footprint of his mare inscribed in the stone is also shown).

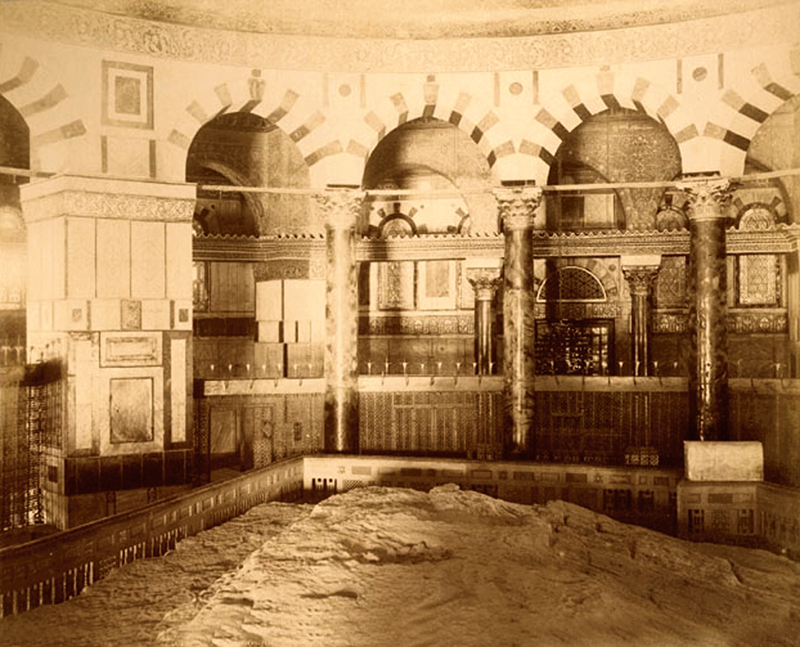

Image opposite: the interior of the Dome of the Rock with the location of the footprint of the Prophet's mare inscribed in stone © The Blatchford Collection of Photographs.

Arabic legends and Islamic theological writings add considerable development to the Qur'an's succinct narrative. The terms in the Koranic text relating to the Remote mosque may come as a surprise at first, given that at the time of the Prophet, there was no mosque in Jerusalem whose name does not appear in the Koran as an Islamic holy place. This interpretation stems from a tradition dating from after the writing of the sura (XVII). The original meaning of «the place where one prostrates oneself before God».» or « sacred place »This text is to be understood as.

The construction of the Dome marked the beginning of a building program that would later include, around 705-709, with Abd al-Malik's successor, Al-Walid I, one of Islam's greatest builders, a real mosque: Al-Aqsa.

The Dome of the Rock, a magnificent monument, is representative of Islamic art; ancient and modern authors alike praise the harmony, balance and perfection of its plan and volumetry. In fact, its layout is based on a whole series of precise geometric properties, making it a veritable receptacle of ancient mathematical esotericism.

The authorship of Syro-Byzantine architects for these two Islamic works is underlined by both technology and decoration. Indeed, the rich mosaics of the al-Aqsa crossing, like those of the Dome, are of Constantinopolitan manufacture. They depict foliage, garlands, vases or canthars of immortality, symbolizing the gardens of Paradise described in the Koran.

Arab authors have commented at length on the ensemble formed by the Dome of the Rock and Al-Aqsa: Ibn Batuta, for his part, considers the entire esplanade, the Haram as-Sharif, which forms the place of prayer. The two constructions would therefore only constitute the martyrium on the one hand, and the «winter hall» on the other, of a vast open-air mosque.

As early as 1900, Swiss archaeologist Max Van Berchem noted the inscriptions, but it was scientist Oleg Grabar who published the first and most in-depth hypotheses on their significance in 1959.

The central, majestic element of an architectural ensemble, the Dome has been restored many times over the course of history. The dome was rebuilt in 1022 and renovated in 1089, 1318, 1448, 1830, 1874, 1962 and then completely in 1994. During the latter restoration, copper plates coated with a thin layer of nickel and gold were installed.

Image opposite: a portrait of Suleiman I the Magnificent (1494- 1566). He is known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the West and the Lawgiver in the East (Turkish: Kanuni; Arabic: القانوني, al-Qānūnī) because of his complete reconstruction of the Ottoman legal system.

Soliman became one of the most eminent monarchs of the 16th century, presiding over the apogee of the Ottoman Empire's economic, military, political and cultural power. He led his armies to conquer the Christian strongholds of Belgrade, Rhodes and Hungary, before being forced to stop short of Vienna in 1529. Public domain.

In the early 9th century, the Abbasid caliph al-Mamun had Abd al-Malik's name erased and replaced by his own.

Subsequently, each reigning dynasty, from the Fatimids to the Ottomans, sought to leave its mark on the building, while undoubtedly preserving its original layout and proportions. Nevertheless, many elements have been replaced in the interior mosaics, including clumsy Mamluk restorations in the cupola, which has been rebuilt many times, and in the painted ceilings, whose motifs can be dated back to the 13th century.

However, it's undoubtedly the exterior decoration that has been most marked by these restorations: in the 16th century, on the orders of Suleiman I the Magnificent, it was completely replaced by this famous Ottoman-influenced ceramic tile cladding.

Map of the Dôme du Rocher

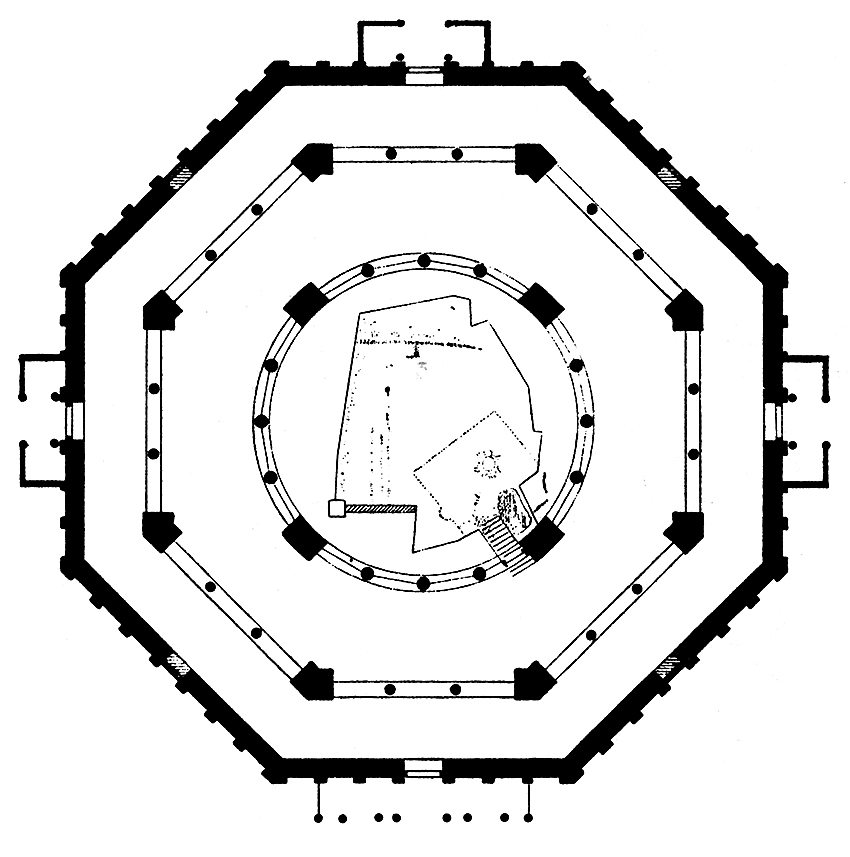

The Dome of the Rock is situated on an artificial rectangular platform opened by eight staircases. Located just off the center of this platform, it follows a plan centered around the focal point that is the Rock, in reality an outcrop of Mount Moriah.

This plan is divided into a first ring in the center, consisting of a first colonnade around the Rock, supporting the dome, and a second octagonal colonnade. These two arcades define a first ambulatory, while a second is located between the second colonnade and the outer walls, also eight-sided. The building is opened by four doors facing the four cardinal points, one of which - the one facing the Al-Aqsa Mosque, and thus the qibla (the direction towards which the Muslim faithful must turn to perform prayer) - being magnified by a larger portico.

Image opposite: plan of the Dome with its four doors. Public domain.

This plan is not new: it is clearly inspired by the Christian models of martyrium, Like the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem and the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, which follow the same octagonal and circular configuration and were built by Emperor Constantine in the 4th century. Disturbing analogies have also been demonstrated with the central octagon of Saint-Simeon-le-Stylite in Qalat Seman (Syria) and the cathedral of Bosra or Saint-Vital in Ravenna (dating from 530).

In the Dome of the Rock, the symbolism lies in the passage from square to circle, from earth to sky, through octagons and polygons.

Computer-generated view of the Dome du Rocher, in profile, perspective and from above. Montage Théo Truschel, with 3 DS Max software.

Outside view of the Dome

Two types of support are used: colored marble columns (blue marble in particular) and masonry pillars. In the octagonal colonnade, two columns are linked by raised arches between each of the eight pillars; in the circular colonnade, three columns punctuate the space between four pillars, supporting semicircular arches with alternating-colored keystones. Each column is surmounted by a capital with acanthus leaves, and wooden tie-beams connect them. This continuous band of beams runs between the capitals and arches for the columns, and between the pillars and spandrels for the piers.

Image opposite: a detail of the façade, with its Ottoman-influenced ceramic tile cladding, Dome of the Rock. Public domain.

The outer wall features numerous clerestory windows. Three of the doorways are marked by two columns, while the one facing the west has an arcade of eight columns. qibla. Sixteen clerestory windows are also found on the drum of the central dome. The double grilles that furnish all these openings, both on the outer wall and on the drum facade, date from the Ottoman period. Originally, the windows were thought to be made of marble lace on the inside and wrought iron on the outside.

Conclusion

In Jerusalem, on the very esplanade of Solomon's ancient Temple, stands one of the oldest Islamic monuments: the Dome of the Rock. Its location at the heart of the high place revered by the three great revealed religions of the Book - Judaism, Christianity and Islam - makes it an eminent symbol.

Image opposite: an aerial view of the Temple Mount with the Dome of the Rock and the Kotel or Western Wall. M. Truschel.

At stake in the Arab-Israeli war on the one hand, and in the ongoing peace negotiations on the other, Jerusalem, along with the West Bank, is at the center of preoccupations throughout the Middle East and among the major powers.

Image below: a general view (detail) of Jerusalem. The Dome of the Rock can be seen in the center of the image, with the Al-Aqsa Mosque on the left. © Patrice Bouton.