Bible, History, Archaeology

History,

Archaeology

Home >

Ezekiel and the «lament over Tyre»,

chapter 27

In the Old Testament, the prophet Ézechiel proclaims a series of prophecies about the pagan nations surrounding Israel. Among them is the «lament over Tyre» (Ézechiel, chapter 27); what does it tell us about this Phoenician city so famous in antiquity and in the Bible?

A favorable geographical location

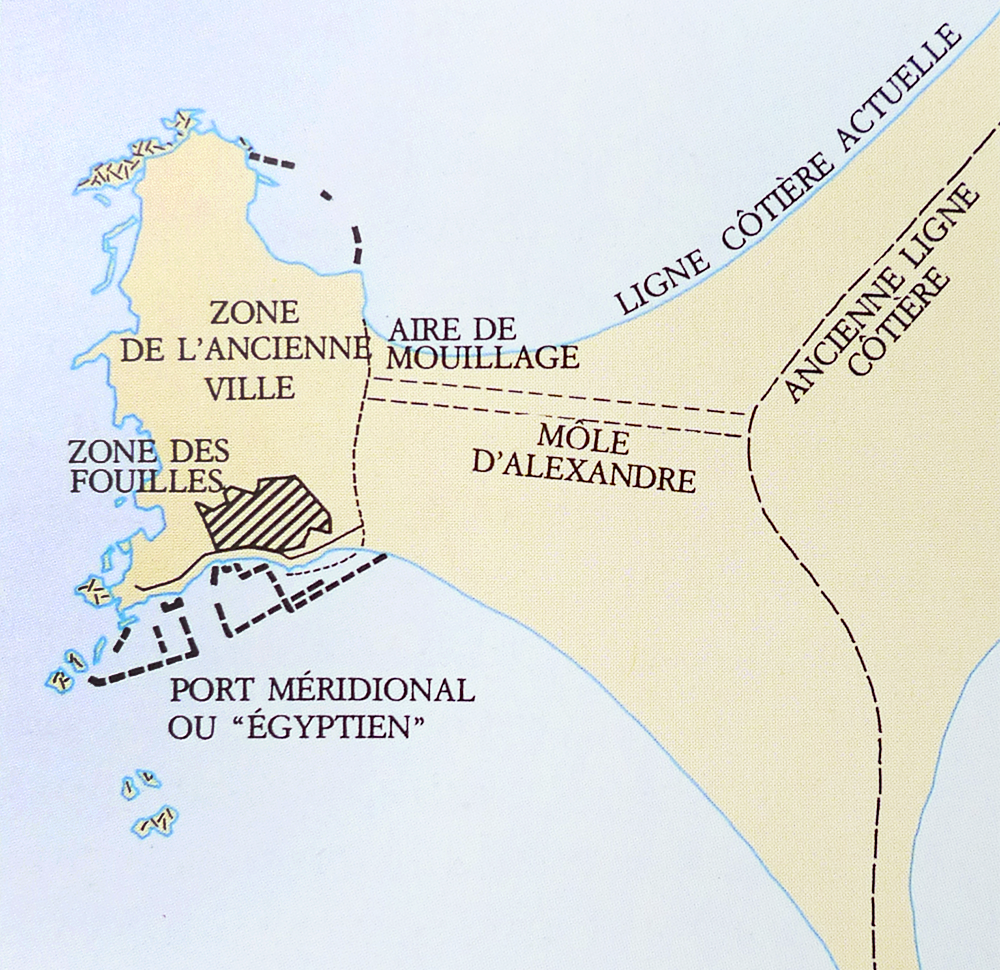

Image opposite: Map of the ancient city of Tyre © Les Phéniciens, Sabastino Moscati. Éditions Bompiani, 1989.

The coast of present-day Lebanon is made up of bays, promontories and islands at the mouths of small, isolated valleys, forming a narrow coastal strip wedged between the Mediterranean and the mountains. Numerous watercourses give access to the sea, some of them leading into the interior, opening up important trade routes, such as the Homs Gap in the north, the main communication route into the hinterland, and the Akko Depression in the south, leading to the Jordan Valley. Numerous ports have been established here since ancient times, including Arwad, Byblos, Sidon and above all Tyre. However, these cities never managed to form a single political entity and remained fragmented.

Phoenicia and its influence, with its home ports and trading posts all around the Mediterranean Sea. Public domain.

An eventful history

Image opposite: statue of Salmanazar III. Incription: ... Salmanazar, the great king, the mighty king, king of all the four regions, ... the mighty rival of the princes of the whole earth (the universe) the great ones, the kings, son of Assur-Nasirapli, king of the universe, king of Assyria, grandson of Tukulti-Ninura, ... Istanbul Museum, Turkey. © Gryffindor.

Image opposite: statue of Salmanazar III. Incription: ... Salmanazar, the great king, the mighty king, king of all the four regions, ... the mighty rival of the princes of the whole earth (the universe) the great ones, the kings, son of Assur-Nasirapli, king of the universe, king of Assyria, grandson of Tukulti-Ninura, ... Istanbul Museum, Turkey. © Gryffindor.

The Phoenician name for Tyre, «Sur», the «rock», comes from the fact that the city was established on an island, virtually impregnable. Its foundation dates back to the Canaanite world of the 3rd millennium (around 2750 BC according to tradition). Its role seems to have been of little importance at the time, as it is not mentioned in the Mari or Ebla archives, and in the second millennium, the Egyptians mention it as a port of call on the way to Byblos. It was not destroyed by the invasions of the «Sea Peoples» around 1200 B.C. and continued to develop.

What made Tyre and the other cities so rich was their role as essential intermediaries between the regions bordering the Mediterranean and Egypt, the Orient and Arabia; their mastery of navigation and their fleets made them indispensable trading partners. However, like the rest of the Southern Levant region, it was confronted by the great empires of Neo-Assyrian, Neo-Babylonian, Persian, Greek and finally Roman times.

During the Neo-Assyrian Empire, from Salmanazar III (858-820) to Assurbanipal (668-631), the Phoenician cities, and in particular the city of Tyre, underwent assaults, subjugations and revolts that were constantly renewed. One of the high points of these revolts occurred in 701, under Tyre's king Luli, who was forced to take refuge in his Cypriot colony of Kition, from where he continued to lead the revolt against Sennacherib, who laid siege to the island for 5 years without being able to take it; Deprived of its resources, the city went through an extremely difficult period; however, the Assyrian king took advantage of the submission of the other Phoenician cities, and Sidon in particular, to hand over to Ittobaal, installed on the throne of Sidon by his care, the territory taken from Tyre which extended from Sidon to Akko. However, in 677, the king of Sidon, Abdimilkot, rebelled against Assyrian fiscal pressure. Assarhaddon reacted relentlessly: he razed the city to the ground, dismantled its ramparts and threw them into the sea; he had a bas-relief depicting his king on a leash; he seized all Sidonian towns and made them Assyrian provinces. In the end, he also imposed a treaty on Tyre, in return for the cession of the two cities of Marubbu and Sarepta. The two Phoenician cities were thus neutralized.

Under Nebuchadnezzar II, Following a revolt, a siege was laid on the city, lasting 13 years (around 585/573 B.C.), and the entire mainland region was devastated, without the Neo-Babylonians succeeding in taking the island, although the king of Tyre had to surrender and pay tribute. This episode is recounted in the lament of the prophet Ezekiel, a contemporary of the events..

Integrated into the Persian Empire after 539, Tyre supplied fleets to the Achaemenid rulers, notably against Greece.

Later (332 BC), under Alexander the Great, the city that refused to open its doors to the conqueror was subjected to a new siege, a jetty was built, the city was taken, pillaged and part of the population massacred.

Image opposite: a silver coin bearing the effigy of Alexander the Great.

Tyre's trade resumed, but never regained its former importance. In 64 BC, Tyre came under Roman rule and became a simple provincial town of little importance.

On the reconstruction of the Balawat Gate in Assyria, details of an assault by Assyrian soldiers on the besieged city of Tyre © British Museum.

Unprecedented sales expansion

«When the produce of your markets came forth from the sea, you satisfied a great number of peoples» (Ezekiel 27, 33). «All the ships of the sea and their sailors were with you to negotiate their wares;» (27:9).

Image opposite: statuette of a Phoenician divinity unearthed at Homs, mid-2nd millennium BC.

The snake coiled around the divinity represents her power over the forces of nature. © Musée du Louvre, Paris.

In the early 10th century BC, Tyre became the most important city in Phoenicia. Its location on a rock and its boat-like shape led Ezekiel to compare it to a ship at the beginning of his lament. Its heyday coincided with the rise to power of Hiram I (circa 950/936), who built the northern port (known as the «Sidonian port» because it was oriented towards Sidon) and laid the foundations for international trade in the Aegean, the southwest coast of Cyprus, southern Crete and the Red Sea. (joint expedition with the Hebrews in search of gold and precious stones). He established a privileged relationship with King David, supplying him with cedar wood for the construction of his palace (2 Samuel 5:11); this alliance continued with Solomon, to whom he also supplied cedar wood for the building of the Temple in Jerusalem but also craftsmen capable of working bronze, gold, ivory inlays in ebony wood, weaving hangings; in exchange, Solomon sent Tyre six thousand tons of wheat, nine thousand liters of olive oil and as much wine every year (180-liter amphorae for transport have been found in a shipwreck off Ashkelon). (1 Kings 5,22 and 2 Chronicles 2,8). It was he who built Tyre's three main sanctuaries, those of Astarte, Baal Shamin and the most famous, that of Melkart with its two steles (or betyls?), one in gold, the other in emerald, which Herodotus was still able to see in his day (c. 484-425 BC); he also had a palace built on the south-western corner of the island and laid out the central market square.

But it was Itho-Baal, former priest of the goddess Astarte (c. 887/856 BC), who consolidated Tyre's hegemony.C.) who consolidated Tyre's hegemony; he built the island's southern port (called «Egyptian» because it faced Egypt) and the walls that protected the city; these fortifications seem to be confirmed by the reliefs on the bronze gates of the city of Balawat, in Assyria, on which Tyre is depicted with a crenellated enclosure featuring towers and two gates. He maintained close relations with the Omri dynasty in Israel (marriage of his daughter Jezebel to King Ahab and introduction of Baal worship in Israel). ; In search of raw materials, he founded the first known Tyrian colony at Kition (Cyprus) for the copper trade.

Image opposite: a bas-relief depicting Sargon II, King of Assyria. Egyptian Museum, Turin.

Subsequently, Tyre underwent incredible commercial expansion throughout the Mediterranean, with the foundation of numerous trading posts and colonies in Cyprus, Sicily, Sardinia, Spain (Tarshish), on the African coast and, of course, the best-known, Carthage (founded in the 9th century BC); all these trading posts were located in regions offering access to mineral resources (copper, tin, iron, gold, silver).

Ezekiel (6th century B.C.) can rightly place Tyre at the center of a trade network that included the Near East, Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula, Egypt, the Mediterranean islands and Spain. Its fleet, sailors and mastery of navigation made it an essential partner for many countries: for example Assyrian king Sargon II, who wanted to invade Egypt, had to call on the Phoenician fleet.

What does Ezekiel tell us about Tyre's wealth?

Image opposite: a mollusc shell (murex) from which indigo and purple were extracted, a rare and precious color worth its weight in gold in Antiquity. Size 7.5 cm x 4 cm. Public domain.

Among the products most mentioned by Ezekiel are dyed and embroidered fabrics: fine linen (byssus) from Egypt, white wool from Damascus, hangings, garments. They were often dyed indigo (blue-violet) or purple (various shades of red); this color was a Phoenician specialty derived from a shellfish, the murex. ounce of this precious dye was worth more than its weight in gold, and its fame spread throughout Antiquity, as it was reserved for the highest state officials; its decline occurred after the 4th century CE.

Cedars from Lebanon were sought after by the Egyptians from the 4th millennium onwards, and we have numerous archaeological traces of this trade, first with Byblos, then with Tyre.

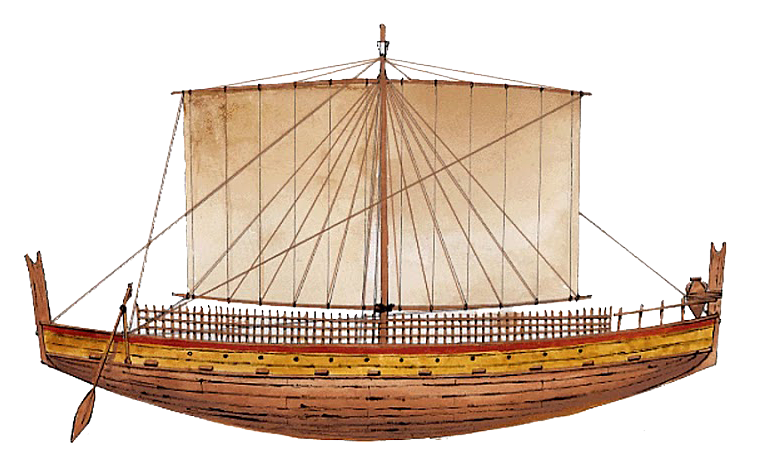

Image opposite: an illustration of an ancient Phoenician ship. Public domain.

The Phoenicians also bought and sold slaves, and the prophet Joel reproaches them for selling Hebrews to the Greeks ; In addition to supplying the city with horses, probably taken from Armenia, the Phoenicians also supplied the city with perfumes, incense and aromatic resins, luxury products that were as valuable as precious metals. Finally, thanks to the availability of fine sands rich in silica, the Phoenicians developed a glass industry as early as the 8th century B.C., not only for luxury tableware but also for earthenware glass paste, producing glassware that they traded all around the Mediterranean.

Thus, the text of Ezekiel provides us with a rich inventory of Tyre's trade, confirmed by numerous archaeological finds of extremely varied goods. It is clear that Tyre was, at the time, the richest trading city in the Mediterranean.

Image above: Small glass pendant masks. These are symbolic images of the Phoenician-Punic material culture, 4th and 3rd century BC ©. Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Image below: Ancient site of Tyre. Of the mighty Phoenician city and, according to the Scriptures, its influence on the Royal Period of Israel, all that remains today are imposing ruins from the Roman and Byzantine eras. © Kareen Truschel.

Image opposite:

Image opposite: