Bible, History, Archaeology

Bible,

History,

Archaeology

Herod I the Great,

the discovery of his tomb

Contents:

Introduction – The discovery – A view of the tomb entrance – The reconstruction

The discovery of King Herod's tomb on Mount Herodion in the West Bank, a dozen kilometers south of Jerusalem, is not only a major archaeological event, but also the culmination of more than half a century of relentless fieldwork.

The discovery of King Herod's tomb on Mount Herodion in the West Bank, a dozen kilometers south of Jerusalem, is not only a major archaeological event, but also the culmination of more than half a century of relentless fieldwork.

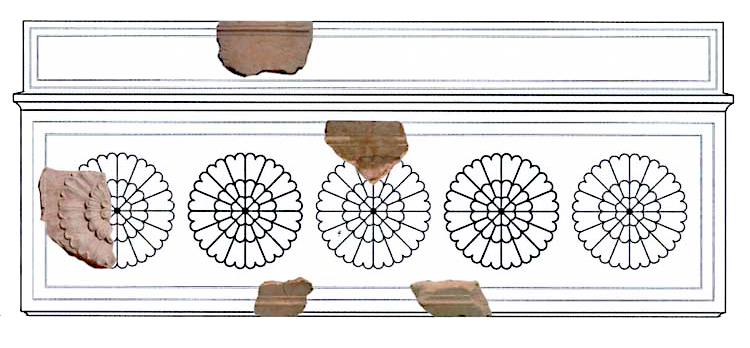

Image opposite: finely sculpted floral decoration. Doron Nissim.

The discovery

The discovery

Image opposite: Professor Ehud Netzer (1934-2010) of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem at the Herodium site. © Doron Nissim.

On May 7, 2007, Professor Ehud Netzer (1934 - 2010) of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and his team announced the discovery of the presumed tomb of the last great Judean king, Herod I the Great. In so doing, they put an end to the enigma of 35 years of archaeological excavations on the site of Herodium, an artificial hill built by Herod around 20 BC to support a palace-fortress. He used it as one of his winter residences, communicating by light signals with other nearby fortresses (Masada, Cypros, Alexandreion). Herodium, today in the West Bank, is located 12 km south of Jerusalem, not far from Bethlehem.

Image opposite: a northeast view of the palace-fortress of Herodion built by Herod the Great. Zondervan Atlas of the Bible / HolyLand images.

Image opposite: a northeast view of the palace-fortress of Herodion built by Herod the Great. Zondervan Atlas of the Bible / HolyLand images.

Excavations had already been carried out in the 1950s by Franciscan monks, then by an Italian archaeological team from 1962 to 1967, and again in 1972 by Professor Ehud Netzer. As the excavations proved unsuccessful, the archaeologists turned their attention to the hill's north-eastern mid-slope. It was known from the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus that Herod was probably buried at the foot of the hill, which dominates the entire region from Bethlehem to the edge of the Judah desert on the shores of the Dead Sea.

Fragments of an ochre stone sarcophagus from Jerusalem have been unearthed from the ruins. Originally, it would have been 2.50 m long. It was closed by a triangular-section lid, decorated with rosette-shaped motifs.

Image opposite: excavations on the slope of Herodion Hill have uncovered the remains of a 10 x 10-meter molded podium © Doron Nissim.

All that remains of the burial site, a two-storey, 25 m-high building erected above a 700-capacity theater, is a monumental 6.5-meter-wide access staircase built especially for the funeral procession, and a 100 m2 cut-stone pavement.

The entrance to the presumed tomb of King Herod at the time of its discovery. © Doron Nissim.

The reconstruction

Professor Ehud Netzer asserts that the dimensions and quality of this tomb could only have been suitable for a ruler of Herod I's stature.

Image opposite: the reconstruction of the sovereign's sarcophagus using elements uncovered at the site. DR.

Image opposite: detail of the molded staircase with a few scattered, finely sculpted remains. Doron Nissim.

According to Ehud Netzer, the mortal remains of the sovereign, and probably those of his relatives, disappeared when the tombs were ransacked during the first Jewish revolt between 66 and 73 AD. The insurgents of the time had turned Herodion into a fortress of refuge for their cause. During the Second Jewish War, 132-135, the fortress once again became a center of resistance led by Simon Bar Kokhba. It is mentioned as such in the papyrii published by J. T. Milik.

Image opposite: a northeast view of the palace-fortress of Herodion built by Herod the Great. Zondervan Atlas of the Bible / HolyLand images.

Image opposite: a northeast view of the palace-fortress of Herodion built by Herod the Great. Zondervan Atlas of the Bible / HolyLand images.