Bible, History, Archaeology

Bible,

History,

Archaeology

Sheshonq I,

the treasures of Solomon's Temple

Introduction

Introduction

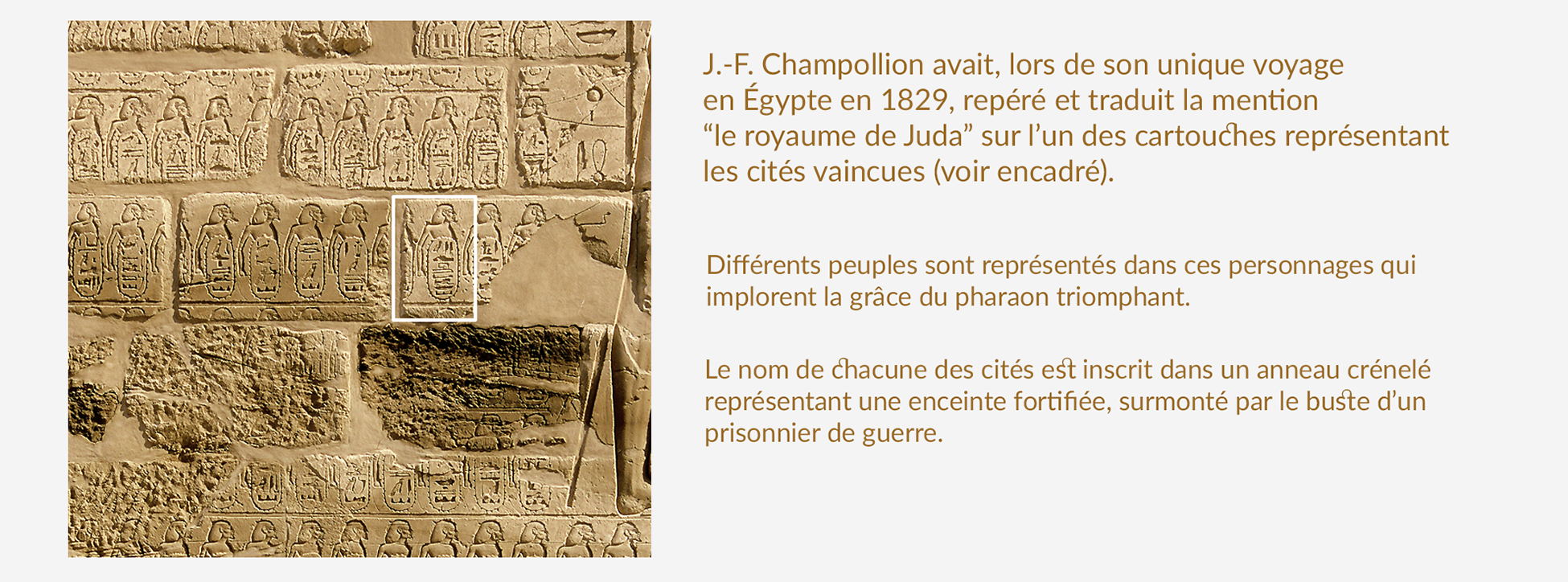

Prince of the Berber Meshouesh tribe of Libyan origin, Sheshonq I ascended the Egyptian throne around 945 BC. Shortly after his accession to power, he embarked on a military expedition unprecedented since Ramses III (20th dynasty), which took him to the two kingdoms of the South (Judah) and the North (Israel). His campaign is recorded on the southern wall of the Temple of Amun-Ra at Karnak.

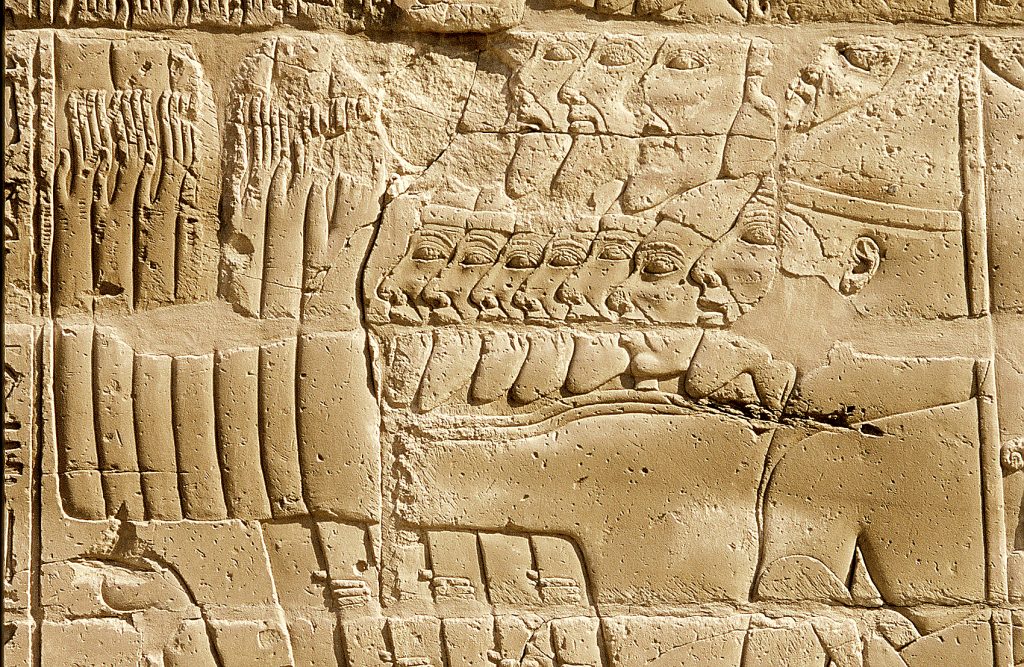

Opposite image: relief from the Karnak temple, Amun-Ra is accompanied by numerous prisoners, including captives from the triumphant Pharaoh's campaign, begging for mercy (detail). © Théo Truschel.

Sheshonq I (945-924 BC) and the XXIInd Libyan dynasty

Sheshonq I, Libyan prince of the Meshouesh tribe, was the founder of the 22nd Libyan or Boubastid dynasty. The Meshouesh tribe had been known to the Egyptians for a very long time: its name appears on the list of Sea Peoples defeated by Merenptah (circa 1213-1202 BC) and Ramses III (1184-1153 BC), in his funerary inscriptions at Medinet Habou, recounts the defeat of Mesher, king of the Meshouesh. The defeated Libyan fighters were incorporated into the Egyptian army, where they quickly assumed commanding positions as a sign of their military valor. Over the next two centuries, they continued to gradually rise to power.

Image opposite: This gold bracelet, 4.7 cm wide and 6.5 cm in diameter, bears the cartouches of

Sheshonq I, was found at Tanis, on the mummy of Sheshonq II. It is decorated with a large eye oujda surmounting a basket of polychrome wickerwork. Egyptian Museum, Cairo. Theo Truschel.

The origins of Sheshonq are partially known to us, notably through a stela that a certain Pasenhor, priest of Ptah at Memphis and a distant descendant of his lineage, left at the Serapeum of Saqqarah during the reign of Sheshonq IV (or V according to specialists); we thus know his ancestors, confirming that they were already occupying positions of responsibility at the end of the previous dynasty. Around 984 BC, Osorkon (known as «the Elder») acceded to the throne during the 21st dynasty, and although we have very few documents concerning him, historians have been able to establish that he was Sheshonq's paternal uncle. All these facts undermine the idea that populations of Libyan culture took advantage of the weakening of the Pharaonic monarchy to seize power. The pharaohs of Dynasties XXII and XXIII bore names of Libyan origin, but they were not «foreigners»; they were perfectly Egyptianized.

Image opposite: among the treasures of Tanis is this gold funerary mask of the pharaoh Psusennes I. Egyptian Museum, Cairo. Theo Truschel.

Like many other pharaohs, he legitimized his power by conferring sacred titles on himself. He succeeded in reunifying the country, despite the reluctance of the Theban clergy, by appointing his sons to high religious and administrative posts and entrusting important positions to members of his family. He was then able to turn his attention to Egypt's former possessions in the Near East and embark on a major military campaign. Shortly after his return from the Levant, and well before the completion of work at Karnak, Sheshonq died and joined his ancestors, probably in the royal necropolis of Tanis (the Tsoan of the Bible), leaving the throne to his son Osorkon I (c. 924-889 BC).

To date, no major tomb has been unearthed in the name of Sheshonq I, and the anonymous burials in the Tanis necropolis, modest in size and anepigraphic, do not seem appropriate for such an important pharaoh, founder of the 22nd dynasty.

Background to intervention in the Levant

Background to intervention in the Levant

Whereas gold had been the dominant metal in Egypt in the 3rd and 2nd millennia, the first millennium saw silver take its place in the economy. With the collapse of the Nubian Empire, African gold became scarce and was replaced by silver (abundant silver was found in funerary furnishings at Tanis). Silver came from mines in Asia Minor, the Balkans, Sardinia and even Spain, and Phoenician merchants dominated trade from their trading posts all around the Mediterranean. This shift in economic geography explains the choice of the eastern Nile delta as the center of power on the Mediterranean, first at Tanis and then at Boubastis (which gave its name to the 22nd dynasty: Boubastide). Securing the flow of money from the Levant certainly explains Sheshonq I's desire to regain a foothold in this region, which Egypt had lost while a powerful kingdom of Judea was emerging and Phoenician cities were gaining strength.

Image opposite: a bust of Pharaoh Osorkon I, son and successor of Sheshonq I. Its hieroglyphic cartouche, bearing the pharaoh's name, is surrounded by a Phoenician inscriptionne in the name of Elibaal, king of Byblos. He maintained the order established by his father, dealing with the clergy of Amun in Thebes, who had difficulty recognizing this dynasty of foreigners. He created a residence near El-Lahoun, and adorned the temples of Heliopolis with gold. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Théo Truschel.

The political situation in Judah and the Levant had evolved and offered ideal conditions for military intervention. The Bible tells us that, always ready to support dissidents and opponents of the Hebrews, Sheshonq I welcomed Jeroboam, King Solomon's overseer of the chores, to his court, in rebellion and flight; as had already happened with the Edomite Hadad, driven from his kingdom by King David (I Kings 11, 14-22).

After Solomon's death, Jeroboam became the first king of the secessionist northern kingdom (Israel), weakening the kingdom of Rehoboam (Solomon's son) in the south (Kingdom of Judah).

The military campaign

In year 5 of Rehoboam's reign (c. 926 BC), on the pretext of nomadic incursions into the Bitter Lakes region, Sheshonq I led a military expedition unprecedented since the 20th dynasty.

This campaign is described in the Bible: «...he had a thousand and two hundred chariots and sixty thousand horsemen; and there came with him out of Egypt an innumerable people, Libyans, Sukkians, Ethiopians...» (II Chronicles 12, 3). The violence of military operations in the Levant is corroborated by archaeology. In Iron Age II levels (c. 980/700 BC), numerous sites show traces of destruction by fire. Biblical and archaeological data converge, but Egyptian sources concerning this campaign must be treated with caution.

To view the movements of the military campaign of Sheshonq I →

Image opposite: Temple of Thutmosis III at Deir el-Bahari. Portrait of the sovereign wearing the khepresh on a polychromed limestone bas-relief. Originally part of a scene presenting four calves as offerings to the god Amun-Ra-Kamutef. Egyptian Museum, Luxor. © DR.

The military campaign continues northwards into the kingdom of Israel, where Jeroboam, Sheshonq's former protégé, flees across the Jordan. Pharaoh's armies halted their advance at Megiddo, on the edge of Phoenicia, where Thutmosis III had been victorious five centuries earlier. There, he erected a stele (of which a fragment remains) and, like his predecessor, proclaimed the victory of his expedition.

The Bubastis Gate in the Temple of Amun at Karnak. Bubastis lies in the Delta, on the eastern bank of the Nile, southwest of Tanis, some 80 km northeast of Cairo. Bubastis is sometimes identified with the Phibeseth of the Bible (Ezekiel, 30, 17). © Théo Truschel.

The effects of the campaign

The effects of the campaign

Sheshonq's military success is immortalized in a text and relief on the outer southern wall of the Temple of Amun at Karnak, at the Boubastis Gate, between the First and Second Pylons. It shows the names of the subjugated cities and Pharaoh's massacre of «Asiatic» prisoners before Amun.

Opposite image: one of the most beautiful pieces in the treasure trove in solid gold, probably from Tanis: the Triad of Osorkon II (circa 872 to 837 B.C.). H: 9 cm; W: 6.6 cm.

This set represents the Osirian family. Around Osiris, who appears crouching, wearing a white crown with two feathers, on a lapis lazuli column, stand Isis, his wife, wearing cow horns, and his son, Horus, wearing the pschent. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Théo Truschel.

It was one of his sons, Ioupout, High Priest of Amon and Governor of Upper Egypt, who reopened the pink sandstone quarries to build a new courtyard that would create a new and impressive front on the Nile, all to the glory of the victorious Pharaoh (image at bottom of page).

However, more than just regaining control of the Levant, these military successes enabled the sovereign to consolidate his position at home, particularly with regard to the Theban clergy who had long been reluctant to recognize his authority. Egyptian inscriptions tell us that his successors donated enormous quantities of gold to the various temples, so much so that a link has been established between this mass of gold and the treasury of the Palace and Temple of Solomon.

Image opposite: the fragment of the stele bearing the cartouches of Sheshonq I, unearthed at Megiddo. © DR.

On the other hand, the presence of a stele at Megiddo does not prove that the Egyptian presence was long-lasting; indeed, all traces of politico-military activity in the region ceased from the end of the 9th century; ; The successors of Sheshonq I seem to have given up all military ambitions in the Levant after a last attempt reported in the Bible (II Chronicles 14, 8-15): a Nubian general named Zerah is said to have led an expedition against the kingdom of Judah, which was crushed by King Asa. We don't know the name of the pharaoh who commanded this campaign, but chronologically, Asa's reign may point to King Osorkon I (924-889 BC).

Introduction

Introduction

Background to intervention in the Levant

Background to intervention in the Levant

The effects of the campaign

The effects of the campaign