Bible, History, Archaeology

Bible,

History,

Archaeology

The Nabataeans and Petra

Image opposite: Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt (1784-1817) in an illustration from his time. Public domain.

The discovery

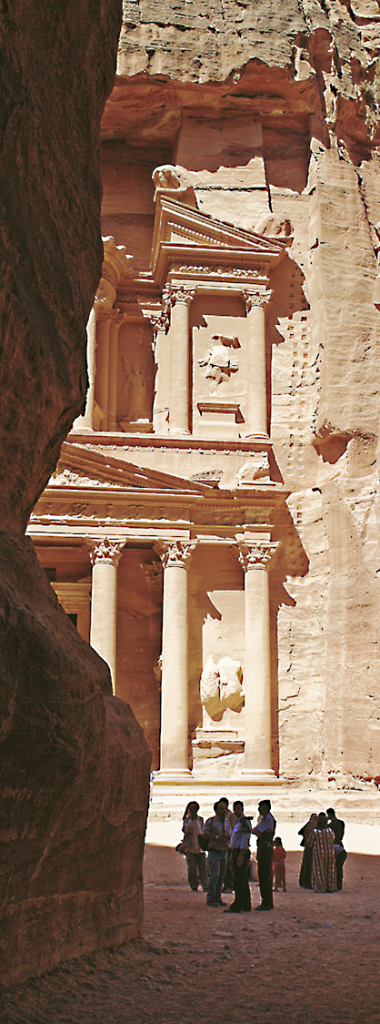

Image opposite: the El Khazneh Fir'awn at the mouth of the Sîq. Marc Truschel

At the foot of the massif, Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, accompanied by his guide, enters the narrow gorge before them, the Sîq. The Sîq is a natural, winding fault about 2 km long. It winds its way between walls of stratified silica, shades of pink, salmon and saffron, in some places almost 120 metres high. Sometimes the walls are so close (3 m) that they hide the sky. Our explorer notices the numerous stelae and niches containing betyls and the strange inscriptions that adorn the corridor in places, as well as the astonishing gutter-like channels dug into the rock to collect run-off water.

After half an hour's walk, turning sharply to the left, the majestic façade of an unparalleled rock monument comes into view: El Khazneh Fir'awn, also known as the «Pharaoh's Treasure», carved out of pink sandstone, 43 m high and richly decorated with pilasters, statues and sculptures.

At this point, Burckhardt was unaware of the name of the forgotten city, and it wasn't until he arrived in Cairo, consulting a few texts by ancient authors, that he identified the ancient Petra (from πέτρα petra, «rock» in ancient Greek; البتراء Al-Butrāʾ in Arabic). This is the capital of the Nabataeans, a people of ill-defined origins who rose from the sands of Arabia, whose civilization reached its apogee in the 1st century BC, before disappearing from human memory.

The first inhabitants of Petra

It is estimated that the Edomites, also called Idumeans in Greco-Roman texts, came to occupy the site of Petra towards the end of the 14th century BC, after expelling the Horian aborigines (Genesis 14:6; 36:20-30). The site's oldest monument appears to be an ancient circular Edomite temple dating from this period: an imposing megalith on which the Nabataeans rebuilt one of their edifices.

Little is known about the occupation of Petra by the Edomites, but they have left a mark on history and archaeology as a people known for the quality of their textiles, ceramics and mastery of metalworking. Egyptian documents dating from the late 13th and early 12th centuries B.C. mention their existence. Genesis cites them as a confederation of Edomite princes, each ruling over their own city (Genesis 36:31-39). Unlike the Hebrews, the Edomites left no literature similar to the Bible, which tells us that their founding ancestor was Esau, Jacob's brother and grandson of Abraham (Genesis 36:1-19).

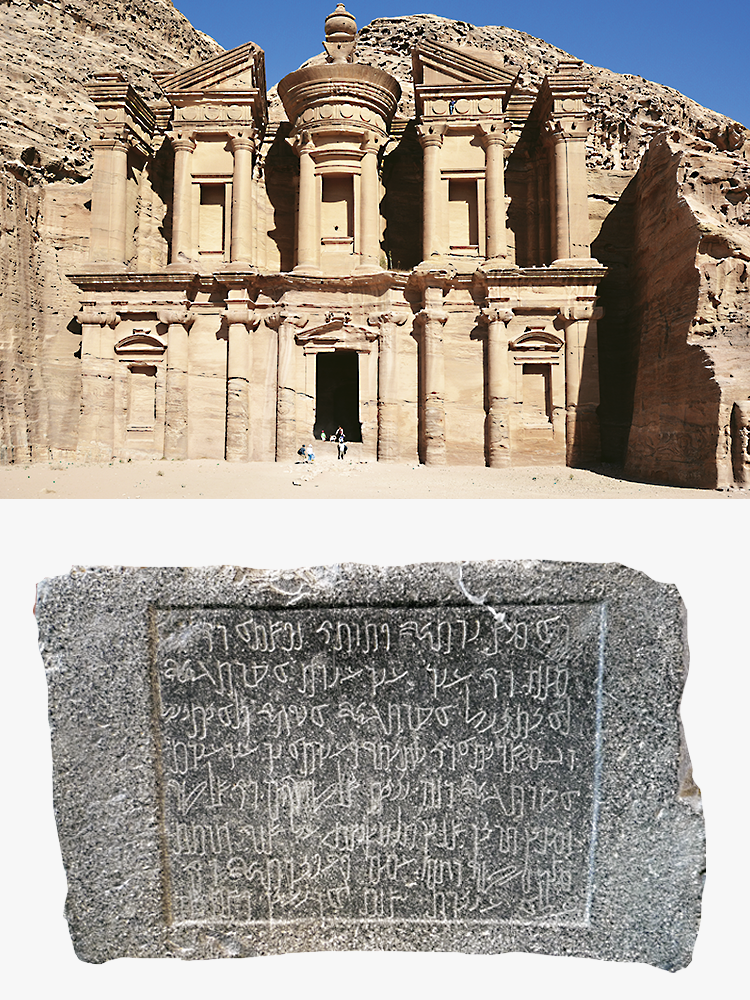

Images opposite: top image: the temple of Ed Deir is the best-preserved and largest monument in Petra © Marc Truschel. Bottom image: Nabataean funerary inscription, Musée du Louvre. Theo Truschel.

Several passages in the Old Testament report an ongoing conflict between the Edomites and the Israelites.

Around 845 B.C., in alliance with other Arab tribes, the Edomites sacked the palace of Jerusalem. 50 or 60 years later, the king of Judah, Amaziah, seized their fortress called Sela. In Hebrew, Sela means «the rock» and refers in the Bible (2 Kings 14:7; Isaiah 16:1) to the Edomite fortress that historians have long identified with Petra or the biblical Bozra. Today, it is generally agreed that Sela lies further north, some 10 kilometers south of Tafila.

Around 735 BC, the Edomites freed themselves from the control of the kingdom of Judea, but became vassals of Assyria, the dominant power in the region in the 8th and 7th centuries.

In 568 B.C., rallying to the neo-Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II, victor over Assyria, they took part in the siege of Jerusalem and the destruction of Solomon's Temple. As a number of Judeans were taken into exile in Babylon, the Edomites settled in southern Judea, gradually abandoning the site of Petra in favor of the Nabataeans. Troubles, wars and deportations marked the end of the Edomite kingdom.

Finally, after the capture of Jerusalem by Titus's Roman legions in 70 CE, history hardly mentions the Edomites.

The Nabataeans

There are two main hypotheses concerning the origins of the Nabataeans: on the one hand, an origin in north-western or central Arabia, and on the other, an origin in north-eastern Arabia, near the Persian Gulf. Other historians place the region of origin even further south.

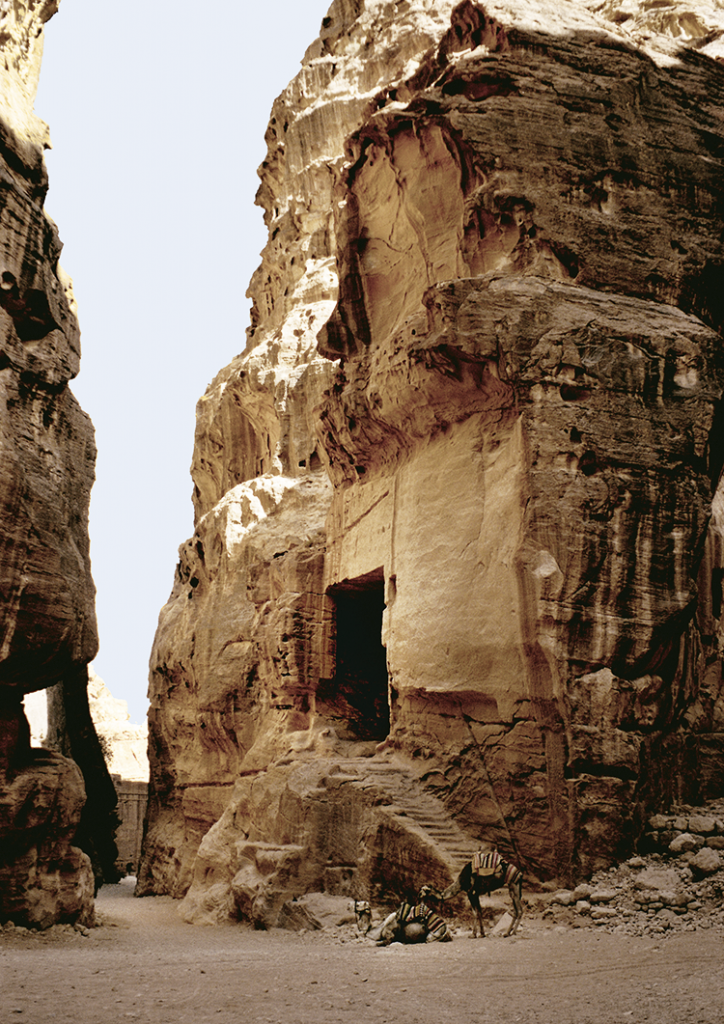

Image opposite: an anonymous rock tomb in the city of Petra © Marc Truschel.

At the time of Assyrian domination of the region, notably during the reign of Teglath-Phalasar (c. 745-727 B.C.), the Hebrews gave the name Nabata to the Arameans, and later the same term was used to designate the nomadic Arab tribes who paid tribute to Assurbanipal (c. 669-626 B.C.). After the fall of the Assyrian Empire, replaced by that of the Neo-Babylonians, followed by the fall of the kingdom of Judah and the deportation of some of its inhabitants in 586 B.C., a politico-cultural vacuum was felt in the region.

The Nabataeans then occupied this territory and developed their trade by settling in the Petra region. Indeed, it's only from this period onwards that Nabataean inscriptions are found in the former territory of the Edomites. There is no precise date for this migration, which surely took place over several decades, but the Nabataeans took control of the coasts of the Gulf of Aqaba and the important Red Sea port of Eilat.

The Arab kingdom of the Nabataeans emerged on the bangs of Syria-Palestine. It benefited from ongoing conflicts between the Lagid kingdom in Egypt and the Seleucid kingdom in Syria. These left the way clear for indigenous principalities such as the Nabataean and Judean Hasmoneans. But the arrival of Rome in the region in the middle of the 1st century B.C. led the Nabataean kingdom to become a client state.

The Great Temple of Petra. One of the few Nabataean monuments in Petra built in stone, and not

carved in rock. Marc Truschel.

Petra's geographical location

The network of caravan routes controlled by the Nabataeans crossed the Arabian desert to transport frankincense, myrrh, spices and aromatics from «happy Arabia» (today's Yemen) to the ports of Gaza and Alexandria. A prosperous trade enabled them to grow rich and found a kingdom which, at its peak, encompassed present-day northern Saudi Arabia and Jordan, southern Syria and the Negev before being annexed by the Romans in 106 CE. It was at the crossroads of this caravan route linking Arabia, Egypt and the Mediterranean ports that the Nabataeans built their capital, Petra, in the 1st century BC. Although most of the monuments found there today are tombs, Petra was not simply a necropolis, but a real city, with public buildings, theaters, temples, markets (see Petra map) and a remarkable hydraulic system.

Image opposite: the Silk Tomb, so named for the moiré colors of the rock. Marc Truschel.

By the time of the Nabataean king Obodas III (30-9 BC), their commercial activities were highly diversified, and the wealth they had accumulated enabled them to import luxury goods to Petra. To protect this wealth, they needed a secure, naturally fortified site. The site, surrounded by high rock walls and out of sight, seemed impregnable.

However, the city's prosperity began to decline in the 3rd century AD, when trade between Arabia and the West took the Euphrates route, to Palmyra's great benefit.

The current situation

Image opposite: a betyl niche (gods usually represented in abstract form by sacred stones) in the narrow Sîq gorge © Marc Truschel.

Today, Petra is considered one of the wonders of the world, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Since 1993, the area surrounding the site has been an archaeological national park.

It fascinates as much for its monuments as for the magical moments when, at dusk, the sun floods the city with light and it is adorned with golden filaments, earning it the name «rose of the sands». But the stone city proves to be quite fragile. Under the action of rain, salt, sun and wind, the rock crumbles inexorably, threatening to return to dust.

New technologies

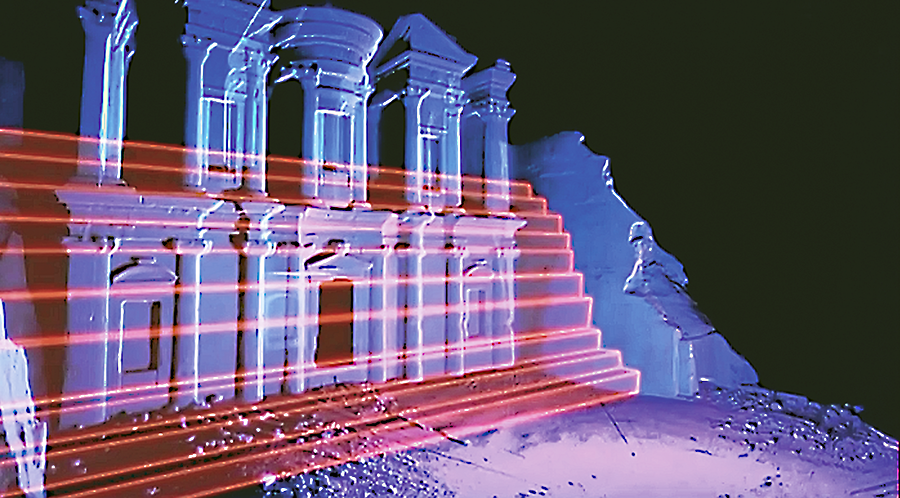

New technologies

Thanks to new technologies, experts led by architect Steve Burrows and equipped with a three-dimensional scanning and 3D acquisition device, have been able to confirm that the Ed Déir was carved out of the rock from top to bottom. Lines are clearly visible on either side of the monument, forming staircases that were erased as the work progressed downwards. Image opposite: © DR.

25 m wide and 40 m high, El Khazneh is certainly Petra's most emblematic monument © Marc Truschel

At 25 m wide and 40 m high, El Khazneh is certainly Petra's most emblematic monument.

New technologies

New technologies