Bible, History, Archaeology

Bible,

History,

Archaeology

The Tell el-Amarna tablets

Introduction

The third discovery was the chance find by a peasant woman in 1887 of over 350 clay tablets in cuneiform script at Tell El-Amarna in Egypt, the former capital of Pharaoh Amenophis IV, also known as Akhenaton.

After translation, it was discovered that they contained the diplomatic archives of the Egyptian court during the reigns of Amenophis III and Amenophis IV, the correspondence of the Canaanite «kinglets» of the 14th century BC who were vassals of the Egyptian Empire, and correspondence with the rulers of Babylon, Mitanni and Syria.

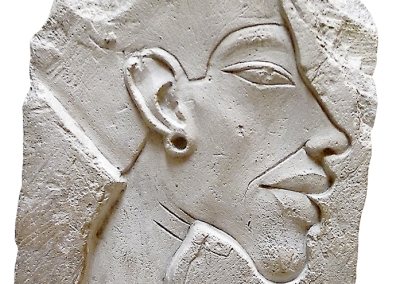

Image opposite: the head of a statue representing Amenophis III © Théo Truschel.

These various letters (tablets) addressed to the Pharaohs set out the social and political context of the Near East, helping us to understand the period that some historians believe corresponds to the «settlement» of the Hebrews in Canaan.

Its presentation

The Arabic name Tell el-Amarna is probably a contraction of the names of the present-day village, el-Till, and of a nomadic tribe, the Beni Amran, who left the desert in the 18th century to settle on the banks of the Nile. Akhetaton means «The Horizon of Aten» in ancient Egyptian.

Image opposite: bust of Nefertiti, Akhenaten's famous wife. © Théo Truschel.

At this point, between Thebes and Memphis, the high cliffs of the Arabian chain on the right bank of the Nile diverge from the river to form a hemicycle twelve kilometers long. It was here, in year 4 of his reign (circa 1360 BC), that Akhenaten laid the foundations of the city that was to be the capital of the Egyptian empire for a quarter of a century. Dedicated to the cult of the single god Aten, the city was quickly built in mud bricks and talatates; four years after its foundation, it was already inhabited by a large population, estimated to number at least twenty thousand. Boundary stelae demarcated the city's territory. On one of them, the king proclaims that Aten himself had chosen this location because it was untouched by the presence of any other divinity. When Tutankhamun left Akhetaten to return to Thebes, the city was abandoned, dismantled by Akhenaten's successors and covered by sand.

Akhetaton is the only city in ancient Egypt of which we have detailed knowledge, not least because it was deserted shortly after Akhenaten's death, never to be occupied again. However, because of its exceptional character and the conditions under which the city was created and then abandoned, it is difficult to know to what extent «Aton's Horizon» was representative of Egyptian town planning.

Discovering tablets

The tablets found at Amarna are kept in museums in Cairo, Europe and the USA; over two hundred are in the Vorderasiatischen Museum in Berlin; fifty are in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo; seven in the Louvre Museum; three in the Moscow Museum; one in the collection of the Oriental Institute in Chicago.

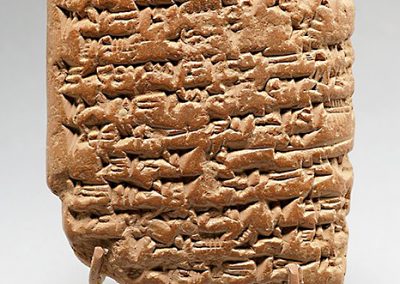

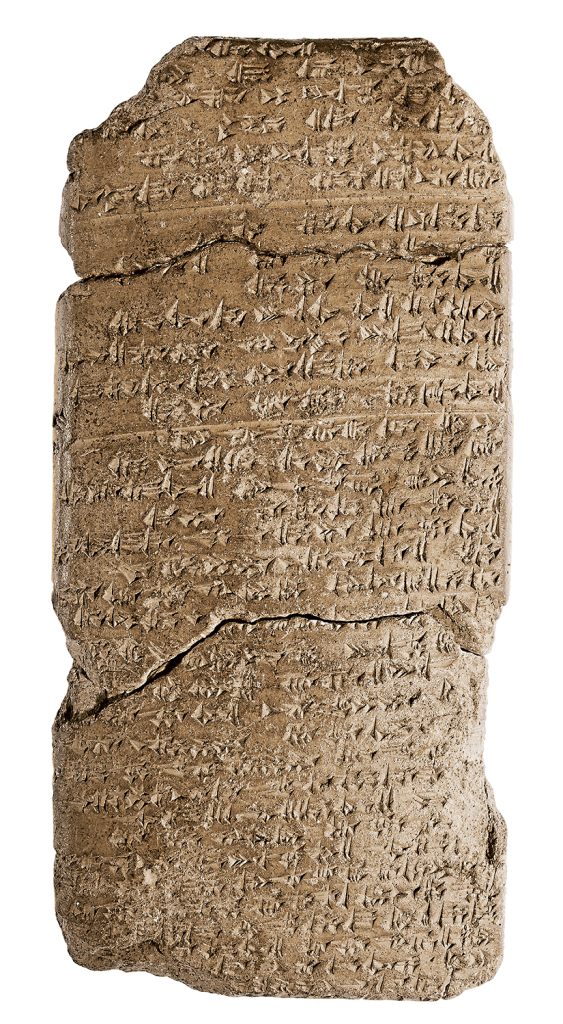

Image opposite: one of the «Letters» unearthed at Tell el-Amarna, written in Akkadian cuneiform, is on display at Berlin's Neues Museum. On this tablet, the king of Jerusalem, Abdi-Hepa, appeals for help against the foreign invaders ‘Apiru. Neues Museum Berlin.

Correspondence between great kings

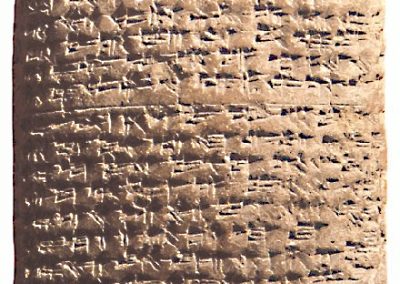

A first set of el Amarna correspondence tablets concerns letters exchanged by the kings of Egypt with the great foreign courts of the time: Babylon (14 letters received), Assyria (two letters), Mittani (fifteen letters), the Hittites (four letters), Arzawa (two letters) and Alashiya (Cyprus, eight letters).

a bas-relief depicting Amenophis IV (Akhenaton). © Théo Truschel.

a bas-relief depicting Amenophis IV (Akhenaton).

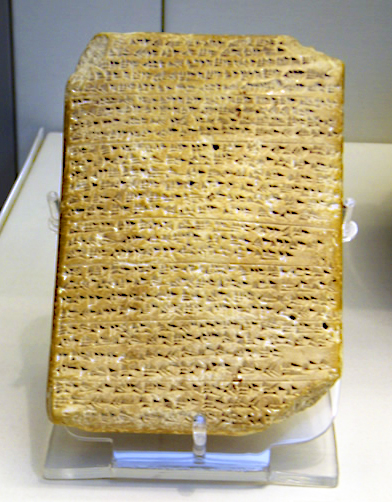

Amarna letter from Ashur-uballit, king of Assyria to the king of Egypt

Amarna letter from Ashur-uballit, king of Assyria, to the king of Egypt © Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A view of the few remaining vestiges of Amarna; the small temple of Aten © Einsamer Schütze.

The first discovery

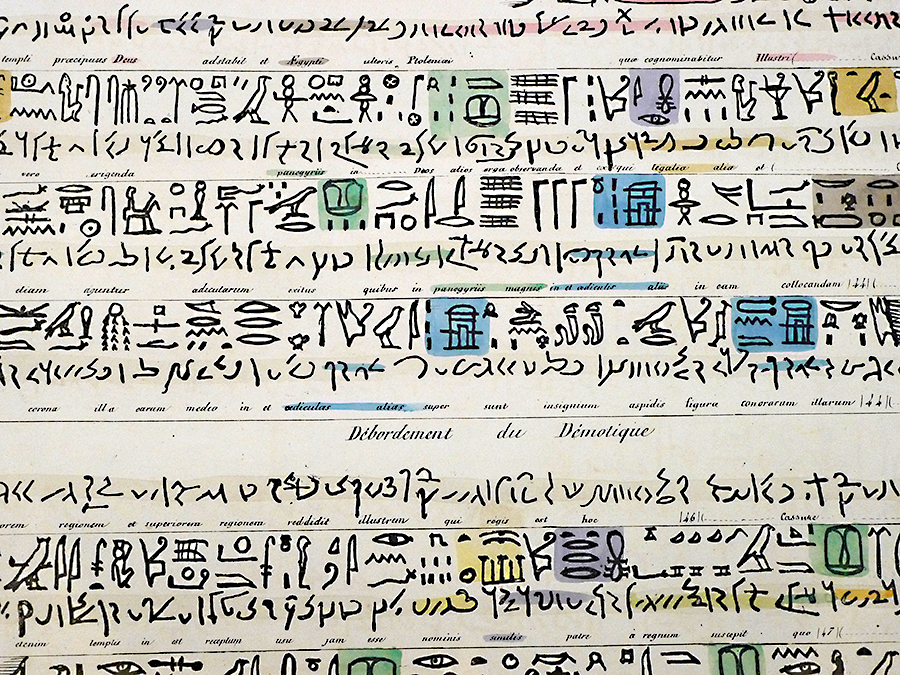

The first discovery was the deciphering of hieroglyphics in 1822 by Jean-François Champollion (1790-1841).

This is the decree of Ptolemy V, 196 BC.

This decipherment was mainly based on a drawing taken from a stele known as the Rosetta Stone, discovered at Rosetta in Egypt's Nile Delta by a French army officer and handed over to the British as a surrender tribute during Bonaparte's military campaign in Egypt (1798-1801).

The second discovery

The second discovery was the deciphering of cuneiform script, the writing of Sumerian, Assyrian, Babylonian and Medo-Persian civilizations. The first approach was made in the early 19th century by G. F. Grotenfed, who began the first decipherments of the three cuneiform languages: Old Persian, Elamite and Akkadian (Babylonian).