Bible, History, Archaeology

Bible,

History,

Archaeology

Joseph,

son of the patriarch Jacob

Contents:

Introduction – Who is Joseph? – A view of the Nile today – Joseph in Egypt – Joseph elevated to dignity – Welcome to the Court – Joseph's tomb – Archaeological and cultural data – A few examples – The tomb of Beni Hassan – An image of the «Asiatids» – Dating from the Egyptian period concerned – An image of Pharaoh on a chariot – Dating Joseph's story – Aper-El's tomb

Introduction

No part of the Old Testament has a richer Egyptian coloration than the story of Joseph. Egyptian names, titles, places and customs appear in the Book of Genesis chapters 37 to 50. Over the last hundred years, historical and archaeological research has made the study of the Egyptian elements of Joseph's story more fruitful than ever. Joseph emerges as an important figure linking the chronicle of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob in Canaan to the later story of the Hebrews' liberation from slavery in Egypt.

Who is Joseph?

The story of Joseph, told in the book of Genesis, is that of one of Jacob's twelve sons and the first of Rachel's two sons (along with Benjamin). He was born in Paddan-Aram (Mesopotamia), six years before Jacob's return to Canaan. He was the son of his old age and his favorite. He made him wear a ceremonial garment (37,3), a tunic of many colors (cf. the paintings in the tomb of Beni Hassan). This paternal preference aroused the jealousy of his brothers, especially when he revealed to them in two dreams that his father, mother and brothers would one day bow before him.

Image opposite: general view of the city of Nablus today (biblical Shechem), with Mount Ebal on the right and Mount Gerizim in the background on the left © Alefbet.

He must have been about 17 years old (37.2) when his father sent him to check on his brothers, who were herding cattle in Shechem (now Nablus). Joseph met his brothers in Dothan. As he approached, his brothers decided to seize him and throw him into a cistern. They then decided to sell him to the Midianites, part of an Ishmaelite caravan on its way to Egypt. Dipping Joseph's tunic in the blood of a goat, they led Jacob to believe that a wild beast had torn the young man to pieces (Genesis 37:1-35).

A view of the Nile with a felucca (originally from Greek epholkion meaning small boat) whose design has hardly changed since Antiquity. givaga 1901779558.

Joseph in Egypt

Joseph in Egypt

Image opposite: a general view of a body of water in the Nile delta © Théo Truschel.

Joseph was sold to Potiphar, Pharaoh's chief of guards, who, having recognized Joseph's skills, entrusted him with the administration of all his possessions. Potiphar's wife tried to seduce Joseph, but when he refused, she accused him of the crime. Joseph was then imprisoned for several years. However, he won the confidence of the jailer, who entrusted him with the supervision of all the inmates.

He had the opportunity to interpret the dreams of two other prisoners, Pharaoh's great cupbearer and great basket-maker (people whose function is the equivalent of ministers), and these dreams came true, just as Joseph had said. The great basket-maker was executed and the great cupbearer reinstated. The latter forgot all about Joseph.

Joseph elevated to dignity

Joseph elevated to dignity

Later, Pharaoh had dreams that no one could explain. Then the chief cupbearer remembered Joseph, who was able to reveal their meaning. The explanation for both dreams was the announcement of a terrible famine that was about to strike the whole country. Seven years of bountiful harvests would be followed by seven years of drought and food shortages.

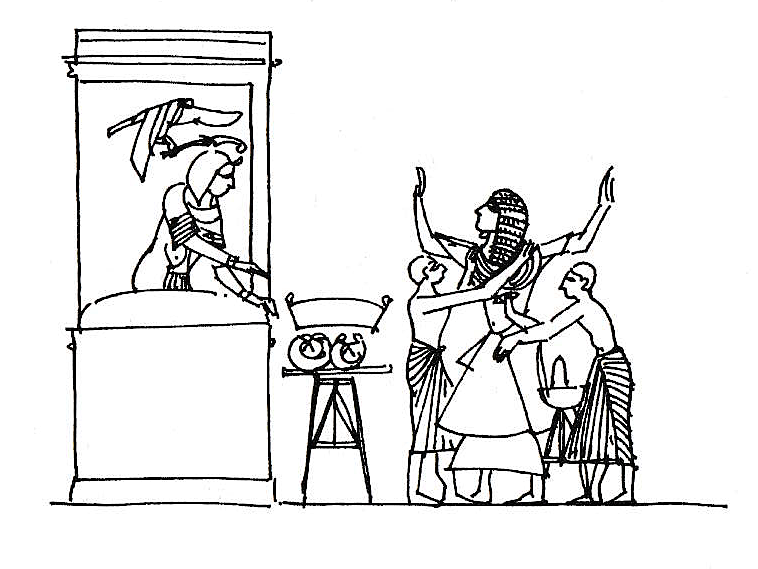

Image opposite: papyrus drawing of a notable receiving a reward for services rendered. Public domain.

Impressed by Joseph's wisdom (41, 9-13, 25-36), the king appointed him superintendent of the royal granaries and minister of state in charge of managing the predicted economic crisis. This placed him among the official figures closest to the sovereign (41, 39-44). Joseph fulfilled this task by stockpiling large reserves of food.

Pharaoh gave him Asnath, a young girl from a priestly family, in marriage. Before the famine began, she had two sons: Manasseh and Ephraim (41:50-52).

Joseph is released from prison. He appears before Pharaoh to explain the two dreams. 3d image. Esteban De Armas 140698225.

During the famine years, his warehouses supplied wheat to Egypt and neighboring countries. Joseph found his brothers, who had come from Canaan to buy provisions; instead of seeking revenge, he forgave them and said:

« ... God has sent me before you to make you subsist in the land, and to make you live by a great deliverance. So it was not you who sent me here, but God; he made me Pharaoh's father, master of all his house, and governor of all the land of’Egypt. »(Genesis 45:7-8).

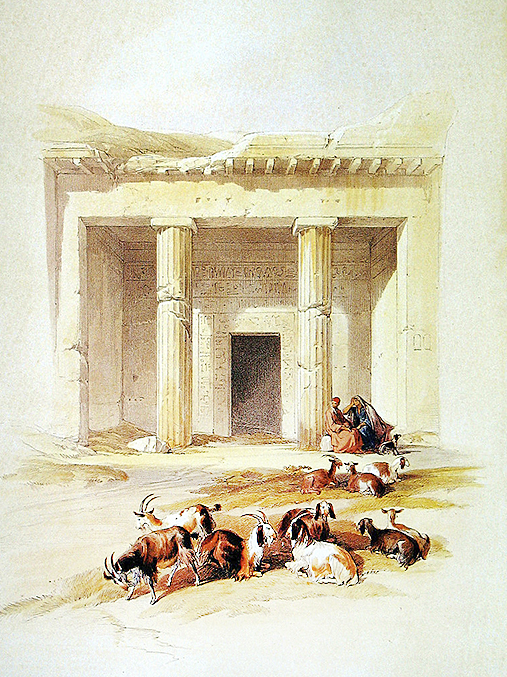

Image opposite: Joseph's presumed tomb at Shechem, painted by David Roberts in 1839 © Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, DC 20540 USA.

He invited them to settle permanently on the fertile land of Goshen, in the eastern part of the Nile Delta. This land was well suited to the livestock farming practiced by the Levantines, whereas the Egyptians «abhorred it».

Joseph's family and their descendants remained on the banks of the Nile for almost four centuries (Genesis 37-50).

The Egyptians mourned Jacob, father of Joseph, seventy days after a forty-day embalming, a figure reflecting Egyptian customs.

Image opposite: an Egyptian embalmer's knife. Mummification instrument with two hooks, bronze or copper?

Image opposite: an Egyptian embalmer's knife. Mummification instrument with two hooks, bronze or copper?

Date approx. 1500 B.C. Length 9.6 cm.

Amitié Sans Frontières« (ASF) endowment fund. Kauffmann Collection. With their kind permission.

This artifact is currently on display at the Toulouse Natural History Museum, as part of the exhibition «Mummies, preserved bodies, eternal bodies» until July 2, 2023.

Joseph died at the age of 110. This notation is highly significant: it refers to a specifically Egyptian fact, that of the ideal age. His body was embalmed and placed in a sarcophagus according to Egyptian custom (Genesis 42 to 50). Later, following Joseph's instructions, the Israelites brought his bones back to Canaan and buried him near Shechem, today's Nablus (Exodus 13:19; Joshua 24:32).

The Hebrews refused to practice mummification (thanatopraxy) even in biblical times, but they did adopt certain Egyptian customs, such as the use of strips into which they inserted aromatics and perfumes, as was the case with Lazarus (John 11:44; Luke 23:56). One exception is the patriarchs Jacob and Joseph, both of whom were in Egypt at the time of their death. Jacob was mummified because he had asked to be buried in the land of Canaan (Genesis 48:27-31), and Joseph because he was Pharaoh's prime minister. Jacob's mummy was, according to his wish, translated by his son from Egypt to the Promised Land, to be buried with his ancestors in Hebron, in the cave that had once been acquired by Abraham (Genesis 50:1-13), and Joseph's was first buried momentarily in Egypt (Genesis 50:14-25), then transported throughout the Exodus (Exodus 13:19 ; Joshua 24, 32), and it was not until many years after his death that he was buried in the land of Israel.

Article by Françoise Biotti-Mache. Doctor of State and Senior Lecturer in Legal History.

Source du site : Cairn.info

For further information: BIOTTI-MACHE Françoise. «La thanatopraxie historique», Études sur la mort, vol. 143, no. 1, 2013, pp. 13-59.

The presumed tomb of Joseph, son of Jacob, today in Shechem (Nablus). The burial site is located at the eastern entrance to the valley between Mount Gerizim and Mount Ebal, northwest of Jacob's Well, on the outskirts of the West Bank city of Nablus. © Robert Hoetink 241427752.

Archaeological and cultural data

The marvellous story that concludes the book of Genesis has prompted archaeological and cultural research aimed at finding traces of it in the field. Far from proving the reality of the story, the results of this work are limited to a few interesting points of comparison between the biblical passages and ancient Egyptian society. Faced with the lack of evidence, some current scholars consider the text to be a fine late literary fable. However, the comparisons ring true, and indicate that the story's backdrop is indeed steeped in this culture.

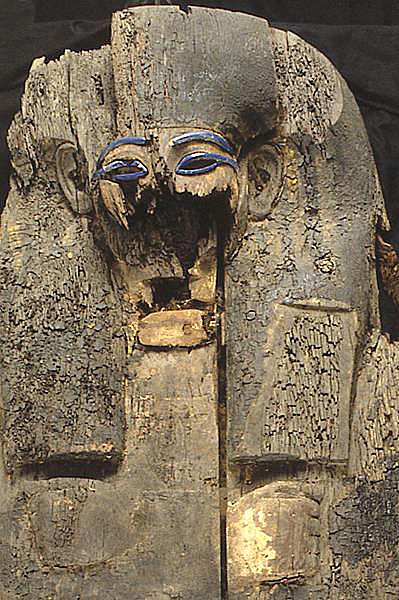

Here we have the coffin of Khnumnakht (1850-1750 BC). This character is totally unknown to us. This coffin shows the multiplicity of texts and decorative panels characteristic of coffin decoration from the end of the 12th to the middle of the 13th Dynasty. The figures and hieroglyphs were drawn by the hand of a skilled artist, and each hieroglyph was carefully painted in the manner prescribed for the time and place in which the coffin was made: Middle Egypt, probably Meir, Khashaba excavations, 1910-15. The Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET).

A few examples

– One economic argument put forward is the sum paid for Joseph's sale by his brothers: one hundred talents of gold (Genesis 37:28), an amount that actually corresponds to the average price of slaves in the first half of the second millennium BC, rising to two hundred talents at the end of the second millennium, then to five hundred in the first;

- The Egyptian mores mentioned in the Book of Genesis are corroborated by certain monuments and some of papyri. Local color abounds in these pages, concerning for example the Egyptian names Potiphar, Zaphnath-paneah, Asenath, Poti-Féra (Genesis 39:18; 41:45, etc.).

The name Potiphar is undoubtedly a transcription of the Egyptian name Pa-di-pa-Ré which means «He-who-gave-Phry».

Asnath, Joseph's wife, most likely an echo of an Egyptian name like Nes-Neith, The one that belongs to Neith«, or rather a name like Iouesenneith, Elle-sera-vouée-à-Neith«.

- The honorific title given to Joseph by Pharaoh, Zaphnath-paneah (translated in Jewish tradition as «the« He who explains hidden things »and in Egyptian Djed-panotcher-ioufânkh which means «the god-said-he-would-live». This last expression contains a remarkable subtlety: its reference to an anonymous divinity («the god», in the singular) omits any Egyptian and therefore pagan deity, in line with biblical monotheism (Genesis 41, 45).

According to Egyptologist Alan Gardiner, the name means «God has spoken». A name rich in plural meanings, as all bring a complementary understanding to the name of this new Egyptian high dignitary;

- Titles of officials (39,1; 40,2-3); ;

- When Joseph became governor of Egypt, he was publicly honored, wearing linen garments and a gold necklace. He wears the pharaoh's ring and travels around Egypt in a ceremonial chariot alongside the king, typical symbols of pharaonic power (Genesis 41, 42-43); ;

«The ceremony of his appointment uses Egyptian elements; Joseph receives the ring and a golden necklace. The ceremonial is well attested in the New Kingdom, but also later. We know of an Ionian, a high dignitary under Psammetichus I in Dynasty XXVI, who boasts, on a statue brought back to Ionia, of having received the gold reward».» (Pascal Vernus).

Image opposite: a pharaoh on his chariot. Public domain.

- Mention of the famines of Egypt (ch. 41)

An inscription dating from a century BC mentions a seven-year famine under Pharaoh Djoser of the 3rd Dynasty; an astonishing, if anachronistic, hieroglyphic text engraved on a granite boulder on the small island of Sehel, south of Aswan. This boulder, known as the «Famine Stele», bears a decree issued by Pharaoh Djoser, one of Egypt's earliest kings. In reality, the inscription is much later, dating only from the Greek (or Ptolemaic, 3rd century BC) period. The text speaks of a disastrous famine lasting seven years, during which the Pharaoh is said to have seen the god Khnum in a dream, announcing the imminent end of the plague. The similarities with Joseph's story (seven-year famine, divinely-inspired royal dream, tax levy) suggest that these phenomena were not so exceptional.

The tomb of Beni Hassan

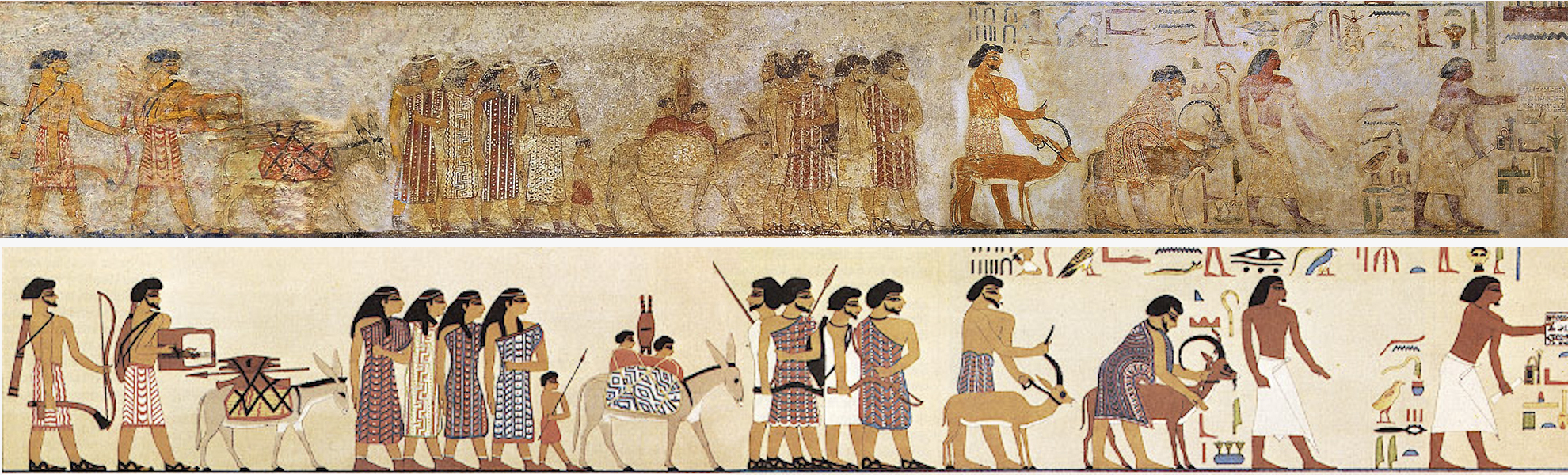

Another clue is a famous mural depicting the lifestyle of desert nomads in Pharaonic times.

Image opposite: a depiction of Khnumhotep II hunting birds in the marshes. © Kurohito.

Near the village of Beni Hassan, a site that owes its name to an Arab tribe that settled there at the end of the 18th century, in Middle Egypt, 18 kilometers south of Al-Minya, brings together on the right bank of the Nile a group of princely tombs dating back to the Middle Kingdom.

Among these thirty-nine hypogea Of the two huge necropolises cut into the cliff, twelve feature wall decorations of great interest, evoking themes borrowed from agricultural life and craftsmanship. These decorations, typical of the Middle Kingdom, are particularly remarkable in tomb 3 of Khnumhotep II (BH3), nomarch of the 12th dynasty. The rock tomb (hypogeum) of Egyptian official Khnumhotep II bears on its walls the image of a Bedouin caravan, whose physical appearance contrasts with that of the Egyptian figures surrounding it. The visitors are dressed in striped tunics, equipped with weapons and accompanied by donkeys and goats, laden with luggage (see full-page image below).

Image opposite: The entrance to the tomb of Khnumhotep II. Painting by David Roberts, circa 1840. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, DC 20540 USA.

The hieroglyphic inscription that completes the image refers to these nomads by the word Aamou, an Egyptian term for the «Asian peoples» of the Levant. By «Asiatic», we don't mean Oriental - but people from eastern Egypt (Canaan territory, hence Semitic). It specifies that this group of thirty-seven nomads brought khôl (eye shadow) and that he was on his way to Khnumhotep II's son. The name or title of their leader, heka khase Abish, can be translated as «prince of a foreign country, Abish».

This fresco is self-dated to year 6 of the reign of Sesostris II, i.e. around 1890 B.C., a date probably earlier than the presumed time of the biblical patriarchs. It is tempting to make a contextual link between these Bedouins and the characters of Joseph and his brothers, or rather Abraham, who spent a brief period in Egypt (Genesis 12:10). The exact provenance of the figures in Khnumhotep II's tomb has long been debated. In any case, this document illustrates the nomadic way of life at the time of the patriarchs, which appears to have remained unchanged for millennia.

«The arrival of «Asian» foreigners in Egypt.

This mural depicts a group of Semitic-looking people entering Egypt. It was discovered at the Beni Hassan burial site in the princely tomb 3 of Khnum-hotep II.

Hieroglyphic commentaries tell us that in the 6th year of the reign of Sesostris II (circa 1876 BC), the nomarch Knoum-hotep set out on a mission for Pharaoh in the Eastern Desert. The aim was to bring back khôl (eye shadow). On their way back, Khnoum-hotep's men escorted a convoy of «Asiatic» nomads (Âamou) coming to Egypt with their families. They brought with them livestock and copper ingots as currency. The leader of the Bedouin caravan is presented as the «heka khase Abish»: the prince of the land of the Abish mountains (above the Petra site in Jordan). Public domain for the upper image, the fresco as it stands today. For the lower image, reconstructed fresco © Morphart Creation.

Dating from the Egyptian period concerned

In the absence of the name of the pharaoh concerned in the biblical text, it would be plausible to place Joseph's arrival in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period (circa 1700/1550 BC), a period when numerous small kingdoms shared Egyptian territory.

From the 20th century BC onwards, sources record the arrival of foreigners from the Levant, who settled as traders, craftsmen, sailors... particularly in the region of the eastern Nile delta. These immigrants acquired increasing authority and began, at a steady pace, to extend their power beyond Avaris (modern Tell el-Daba) even before the end of the 18th century BC.

It was Manetho (3rd century Egyptian historian) who referred to the kings of Avaris as Hyksôs (derived from two Egyptian words Héqaou-Khasout which means «princes of foreign lands»), echoing the term used by the Thebans to disqualify their opponents.

In the 17th century, two centers of power emerged, one in the south, around Thebes (today Louqsor), the other in the Delta, with Avaris as its capital.. The importance of Avaris' trade with the Levant, East Africa and the eastern Mediterranean gave rise to a multicultural local society, where Egyptian culture and Levantine aspects (tombs, weapons, worship of Baal...) coexisted. This northern kingdom extended as far as the other side of Sinai, at Charouen (south of present-day Gaza), at the mouth of the roads linking the land of Canaan with the regions east of the Jordan. In this context, the appointment of a Levantine to the post of vizier seems entirely plausible.

A material clue can be found in two verses of Genesis, which state on the one hand that Joseph was honored « on the second of the state tanks »(Genesis 41, 43), and that the king of Egypt allowed Joseph to bury his father Jacob in Canaan«.« with chariots and riders »(Genesis 50:9). The introduction of the chariot into Egypt goes back precisely to the time of the Hyksos: this element makes the Second Intermediate Period a possible indication for the entry into Egypt of Jacob's family.

The absence of Egyptian archives mentioning a vizier named Joseph, or rather Tsaphnath-Panéach, can be explained by the desire of the Theban dynasty, which defeated Avaris in the mid-16th century, to erase all traces of this period.

Through propaganda, Theban scribes developed the idea that the king of Avaris was a foreigner, an «Asiatic», whom true Egyptians had to get rid of. In reality, seizing Avaris was a vital necessity for Thebes to gain free access to the eastern Mediterranean and the Levant.

Another passage in Genesis also contains names and titles of unmistakably Egyptian origin: «Pharaoh called Joseph Zaphnath-paneah, and gave him Aseneth, daughter of Potiphar, priest of On, to wife.» (Genesis 41, 45). The name of the dignitary Potiphar can be likened to the expression Pa-di-pa-Râ meaning «he who gives Ra». Potiphar is also presented as «priest of On», a probable reference to the Egyptian city of Onou, better known as Heliopolis and dedicated to the worship of the sun (Ra). Similarly, Joseph's wife is called Aseneth, a name that can be translated as «next of the goddess Neith».

An illustrated 3d battle scene of an Egyptian chariot with the pharaoh shooting an arrow and his driver. © Oliver Denker 1872907897.

Dating Joseph's story

The Hyksos were finally driven out of Egypt by the native Theban princes, who restored the country's independence.

Substantial traces of the Hyksos kingdom have been found within the walls of its ancient capital, the city of Avaris, today identified with the present-day archaeological site of Tell el-Daba. Situated on a branch of the Nile in the eastern delta, the city was strongly protected by a thick wall. Excavations have revealed a layer of typically Syro-Palestinian culture between several levels of occupation, containing traces of fighting and a destructive fire: no doubt signalling the capture of the city by the southern Egyptians. Numerous small scarabs found on site bear the names of several Hyksos kings, including those of Yakub-Her and Yakob-Aam. The obvious similarity between these names and the Jacob anthroponym suggests cultural or ethnic proximity, and confirms the Semitic origin of these occupants.

Image opposite: a seal of the Semitic king of Avaris, Apophis of Dynasty XV. MET.

It would be risky to attempt to be more precise, yet we must cite a little-known testimony found in a text from late antiquity and attributed to the Egyptian priest Manetho (3rd century BC). This author, who composed the first history of Egypt, puts forward a name for the sovereign who is said to have known Joseph: this would be Apopi I, or Apophis, a Hyksos king of the XVth dynasty who reigned from 1580 to around 1540. The document, known indirectly through the Byzantine historian George the Syncelle, reads as follows:

Image opposite: a battle, illustrated in 3d, of Egyptian soldiers. © Oliver Denker 2002509602.

What little information we have about this king comes from a literary document, a kind of poem inscribed on the Sallier papyrus in the British Museum. In it, we read that it was Apopi who triggered the fatal war against the southern Egyptians, in a strange and clumsy provocation: he reproached the Theban princes for letting their hippopotamuses make noise at night and prevent him from sleeping! The war was lost by his successor, Khamudi, and ended with the Hyksos being expelled from Egyptian territory.

Image opposite: a hippopotamus cast in earthenware, a ceramic material made from ground quartz. Under the blue glaze, the body was painted with lotuses. These river plants represent the marshes in which the animal lived, but at the same time their flowers also symbolize regeneration and rebirth, as they close each night and reopen in the morning. Around 1961-1878 B.C.

Image opposite: a hippopotamus cast in earthenware, a ceramic material made from ground quartz. Under the blue glaze, the body was painted with lotuses. These river plants represent the marshes in which the animal lived, but at the same time their flowers also symbolize regeneration and rebirth, as they close each night and reopen in the morning. Around 1961-1878 B.C.

For the ancient Egyptians, the hippopotamus was one of the most dangerous animals in their world. The huge creatures were a danger to small fishing boats and other river craft. MET.

The problem is that Manetho then confuses the Egyptian war of independence against the Hyksos with the liberation of the Hebrews led by Moses, two very different events that make the information highly uncertain and questionable.

The possibility that the patriarch Joseph entered Egypt during the Hyksos period is still debated. Other solutions have been considered, including a higher chronology placing Joseph's life during the Middle Kingdom, perhaps during the 12th dynasty (circa 1991-1786 BC). But the Hyksos hypothesis remains the least unclear for conservative biblical scholars. On the other hand, a majority of historians today consider the story to be no more than an imaginary tale or a text for religious edification.

The tomb of Aper-El, the vizier with the forgotten Semitic name

A Semite at the highest level of the’Éstate

Based on an article by Alain Zivie, Biblical Archaeology Review 44:4, July/August 2018.

Thanks to the discovery of its hypogeum, This man appears in archaeology and history as a prominent figure in New Kingdom Egypt. He held high office in the last decades of the 18th dynasty, under the reigns of Amenhotep III and Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten), corresponding to the famous Amarna period (c. 1391-1353 BC).

Image opposite: fragments of planks from the funerary material unearthed in the tomb of Aper-EL. Biblical Archaeology Review (BAR). Alain Zivie.

Generally known by the Egyptian spelling of its name, ‘Aper-El or ‘Aperel (but certainly not ‘Aper-el, as is sometimes found, because El is the name of a deity and as such requires a capital letter), his fame extends beyond the circle of Egyptologists. This important notable is also of interest to Near Eastern and Late Bronze Age specialists, as well as biblical scholars and historians of religion, for two reasons:

- Firstly, because of its Semitic name containing the name of the god El, also known from the Bible;

- Secondly, because of its link with Pharaoh Akhenaten, too often wrongly presented as the «creator» of monotheism.

The name ‘Aper-El is written in Egyptian ‘Aperiar (‘pri3r), iar (i3r) being an Egyptian spelling for ial (i3l). Note also that the name can sometimes be shortened to ‘Aperia (pri3). We recognize in the second element, i3r / l, the Egyptian way of writing «El», the name of a prominent Syro-Canaanite god, which later became a designation of God in the Bible (also appearing in its plural form), Elohim). But in its singular form, the name was used in other biblical names, many of which are still in use today, such as Daniel, Raphael, etc.

Image opposite: one of the funerary masks from the sarcophagus of ‘Abdiel-El © Revue Biblical Archaeology Review (BAR). Alain Zivie.

Image opposite: one of the funerary masks from the sarcophagus of ‘Abdiel-El © Revue Biblical Archaeology Review (BAR). Alain Zivie.

As for the first element, ‘aper (‘pr), even though it recalls an Egyptian verb meaning «to equip», it is an attested way of writing a non-Egyptian word: the Semitic ‘abed (‘abd, ‘abdou), or «servant». Consequently, the name ‘Aper-El (or ‘Aperel) was actually pronounced something like ‘Abdiel (‘Abdi-El), and it meant «the servant of the god El» (not «the servant of God»).

His grave

With its exceptional contents, his tomb at Saqqara is not only the main source of our knowledge of ‘Abdiel (‘Aper-El), but above all the only one known to date.

Abdiel was buried with his wife and one of his sons, probably the eldest, at Saqqarah, the main necropolis of Memphis. His rock-cut tomb is located almost at the southeast corner of the cliff, in the area known as the Bubasteion.

The tomb had already been probed by British archaeologist William Flinders Petrie in 1881, who copied some of the panels visible in the accessible parts of the chapel (level 0).

The «resurrection» of the vizier began in 1976 with the work of Alain Zivie. ‘Aperia (‘Aper-El).

As Alain Zivie has discovered from the inscriptions on his tomb and his funerary material, ‘Abdiel (‘Aper-El) had several titles, corresponding to very important functions and the highest rank at court and in the state. The most commonly used was «chief of the city, vizier» (mr niwt tj3ty), which is usually rendered as «vizier». But he also bore the title, often mentioned just before his name, of «father of the god» (it ntjr), with «god» designating the Egyptian king. This title implies a real closeness to the sovereign, for whom the bearer was a sort of principal advisor, and refers to a king whom the bearer had known as a child and helped to educate. Two other prominent men, formerly «generals of the chariot», bore the title of «father of the god»: Yuya, Amenhotep III's father-in-law, and Ay, who became king after Tutankhamun, but neither had been a vizier.

Image opposite: one of the funerary masks from one of the sarcophagi uncovered in the tomb of ‘Aper-El © Revue Biblical Archaeology Review (BAR). Alain Zivie.

It should be noted that ‘Abdiel (‘Aper-El) is often presented in scholarly literature as a «foreigner». Of course, this assertion is based solely on his name. But a non-Egyptian name does not imply that the individual is a «non-Egyptian». Rather, it denotes a foreign origin, or the foreign origin of the individual's father and/or mother, which is not the same thing. In the case of our vizier, we can say that everything in his tomb (the names of his family members, the funerary apparatus, the gods mentioned, etc.) is Egyptian and only Egyptian.

But at this final stage in the presentation of’Abdiel (‘Aper-El), we must mention a question that cannot be avoided, even if it is highly speculative. We feel obliged to mention it, especially in this article. Although probably of foreign origin, ‘Abdiel reached a high social position and was particularly close to the king or kings of Egypt. Consequently, the story of Joseph, son of Jacob, in the book of Genesis comes to the mind of every Egyptologist, Ancient Near East specialist, biblical scholar and so on. This beautiful tale shows the rise of a young «Oriental» to the rank of second to the king of Egypt. Previously, we knew of a few (rare) examples of such historical ascents to illustrate Joseph's story, but none that placed the hero on the level of vizier, «father of the god» and other lofty titles. There can be no doubt that the discovery of ‘Abdiel changes the situation. But analogy has its limits. We're talking about’to illustrate, and not confirm or’invalidate Joseph's story. There is a fundamental difference between the nature of archaeological and historical research on the one hand, and a literary narrative with national and religious implications on the other. As an Egyptologist and discoverer of’Abdiel, Alain Zivie reminds non-specialists, and even some specialists, to be extremely cautious and avoid confusing these completely different fields.

Joseph in Egypt

Joseph in Egypt Joseph elevated to dignity

Joseph elevated to dignity

Image opposite: an Egyptian embalmer's knife. Mummification instrument with two hooks, bronze or copper?

Image opposite: an Egyptian embalmer's knife. Mummification instrument with two hooks, bronze or copper?

Image opposite: a hippopotamus cast in earthenware, a ceramic material made from ground quartz. Under the blue glaze, the body was painted with lotuses. These river plants represent the marshes in which the animal lived, but at the same time their flowers also symbolize regeneration and rebirth, as they close each night and reopen in the morning. Around 1961-1878 B.C.

Image opposite: a hippopotamus cast in earthenware, a ceramic material made from ground quartz. Under the blue glaze, the body was painted with lotuses. These river plants represent the marshes in which the animal lived, but at the same time their flowers also symbolize regeneration and rebirth, as they close each night and reopen in the morning. Around 1961-1878 B.C.