Bible, History, Archaeology

History,

Archaeology

The different names of the Bible

The different names

As early as the first decades of the 2nd century B.C., various names were used to designate the first set of Holy Books. The first of these was the «Law» or «Books of the Law», or «Book of Moses». In Hebrew, we say ha-séfèr «The Book». After the Pentateuch was translated into Greek in Alexandria, the Law or nomos, then becomes hey biblos, the Book (Septuagint version).

The Greek translators of the ancient Hebrew scrolls used the expression ta biblia. In Greekhis expression is a masculine plural meaning «the Books». While many ancient Greek expressions include biblos or biblion («the books» or «sacred book», etc.), the New Testament authors rather speak of hai graphai, Scripture:

Image opposite A reconstructed scene of a Massoret copying a page from a scroll of the Law. © « the revealed secrets of the Bible« . Arte TV.

But it was only in the 2nd century that the term biblia, the singular feminine term that gave rise to the French word bible, used by the Church Fathers (Clement of Alexandria, Origen, etc.) to designate all the writings of the Old and New Testaments.

In front of the Western Wall in Jerusalem, an Orthodox Jew teaches his grandson «the chema», Listen to Israel ! the central prayer of morning and evening services in Judaism (Deuteronomy 6:4). Damon Lynch.

The composition of the Bible

The Bible comprises a collection of texts considered sacred by both Jews and Christians. Different religious groups may include different books in their canon and in different order.

See the table of Old Testament books →

Since the 8th century, the Hebrew version of the Bible has been spoken in Hebrew. TaNaKh, an acronym derived from the titles of its three constituent parts: the Torah (the Law), the Nevi'im (the Prophets) and the Ketuvim (other writings).

Image above Procession of several sifrei Torah during a Jewish festival. Felix Lipov 248715673.

The various Christian denominations refer to the Tanakh as the Old Testament (or First Covenant). Other ancient texts (Apocrypha) are added in Catholic versions. The Christian version of the Bible also contains the New Testament, a collection of writings about Jesus Christ and his disciples. These are the four Gospels, the Acts of the Apostles, the Epistles of Paul, the Hebrews, James, Peter, John, Jude and Revelation.

The Bible is thus a collection of highly varied writings (accounts of origins, legislative texts, historical accounts, sapiential, prophetic and poetic texts, hagiographies, epistles) written between the 8th century BC (according to some scientists, even earlier) and the 2nd century BC for the Old Testament, and the second half of the 1st century, or even the beginning of the 2nd century, for the New Testament.

Image opposite Discoveries in the Near East shed light on biblical history. Some tools for studying the Bible. © oneblink1.

Ptolemy and the Septuagint

Image opposite: Ptolemy II, Cabinet des médailles, Bibliothèque nationale de France. Cameo representing Ptolemy II as Alexander the Great. Enameled gold mounting by Josias Belle, Paris, late 18th century.

The 72 Jewish scholars (six from each of the twelve tribes of Israel) were responsible for this translation, which, in their honor, is known as the Septuagint Version. Tradition has it that the high priest of Jerusalem, Eleazar, agreed to Ptolemy II's request on one condition: the liberation of the Jews of Judea, taken prisoner and enslaved in Egypt by the Pharaoh's father, Ptolemy I.

Gold coins :

Octadrachme in effigy of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (c. 285-246 BC), Greek ruler, accompanied by his wife and sister Arsinoe II.

He is said to have been responsible for the development of the Septuagint. © Bonhams.

Image of a Sefer Torah with its reading pointer (yad). The Sefer Torah, or Torah scroll, is a handwritten copy of the Torah (or Pentateuch), Judaism's holiest and most revered book. © Merlin.

Image of a Sefer Torah with its reading pointer (yad).

The Samaritan Passover. Only their version of the Pentateuch is considered authentic, to the exclusion of all other books. Danny Yanai.

The Samaritan Passover. Only their version of the Pentateuch is considered authentic.

The reading of the Torah follows a rite defined over two millennia ago, and still scrupulously followed by Orthodox Jews. © DR.

The reading of the Torah follows a rite that has been defined for over two millennia, and is still scrupulously followed by Orthodox Jews.

Find out more

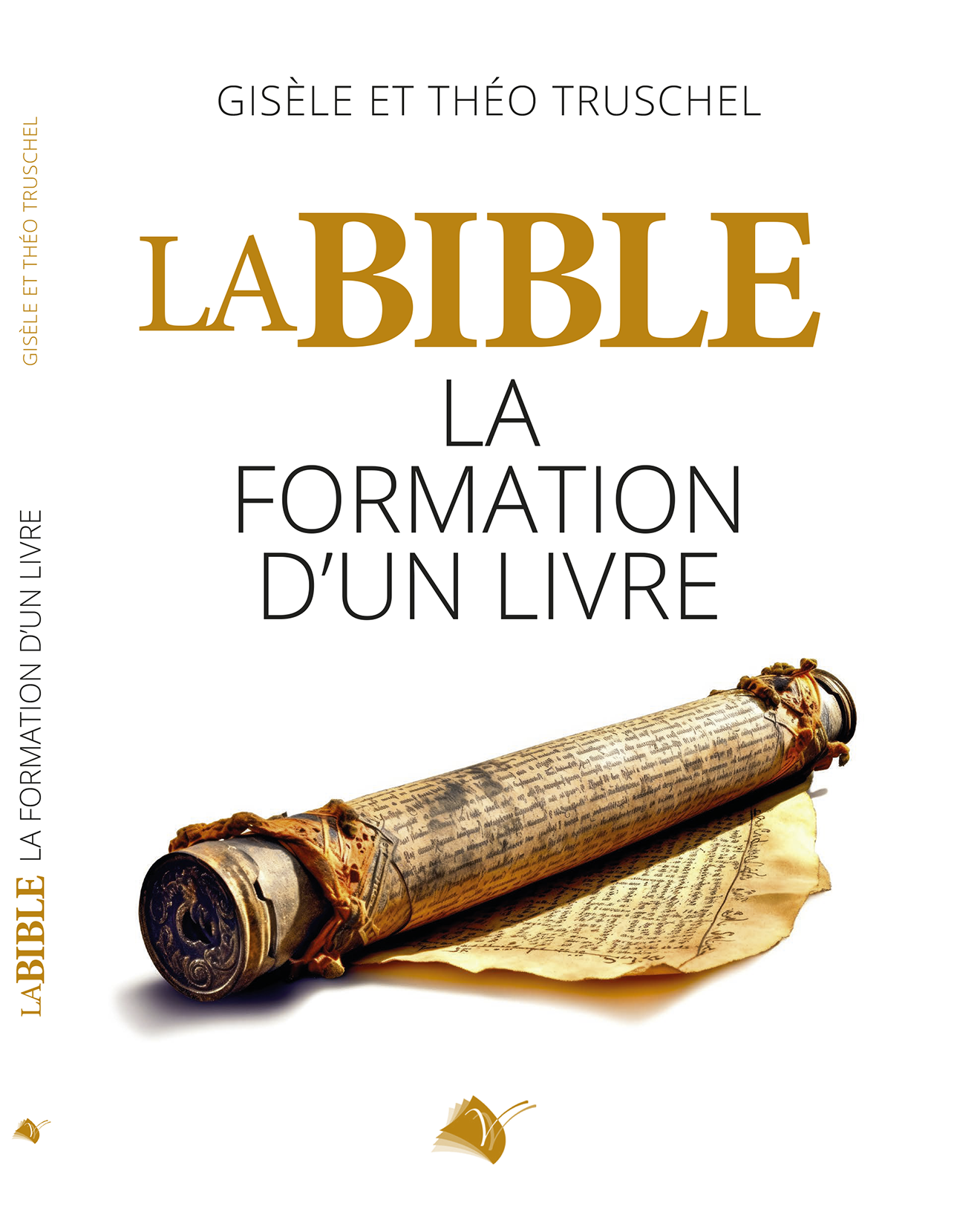

TRUSCHEL Gisèle and Théo and , The Bible, the making of a book.

History and archaeology collection.

Éditions Viens et Vois, December 2023, Lyon.

“The Bible, the making of a book” includes information as close as possible to the most recent discoveries. The historical and archaeological knowledge, the prior writing of the reference work “The Bible and archaeology”(Éditions Louis Faton), and Théo Truschel's many contributions to magazines, leave no doubt as to the quality of the work that emanates from his research. His wife Gisèle, a history teacher, is a more than legitimate co-author in this editorial work. Gisèle and Théo Truschel have succeeded in making this book attractive, accessible and useful for all those who have questions about the origins of the Bible, a worldwide bestseller and a source of faith for humanity.

Fabio Morin