Bible, History, Archaeology

History,

Archaeology

Home > Historical figures > Figures of the TA > Egypt >

Psousannes I, pharaoh

The treasures of Tanis

In 1939-1940, the spectacular discovery by French archaeologist and Egyptologist Pierre Montet and his team of the tombs of the pharaohs of the 21st and 22nd dynasties at Tanis, with their splendid treasures, did not have the worldwide impact it deserved, as the Second World War was breaking out in Europe.

Tanis

Tanis

Until the accession to the throne of Smendès I (c. 1069-1043 BC), first pharaoh of the XXIst dynasty, Djanet (Tanis, in Greek), is just a small fishing village on the eastern delta, which in the 19th century was annexed to the town. name of Lower Egypt; to transform it into a capital befitting their rank, the first rulers of the 21st dynasty dismantled Pi-Ramses, the city built on the nearby branch of the Nile by Ramses II near the ancient Hyksos capital of Avaris. Entire blocks of Middle Kingdom and New Kingdom monuments were transferred there.

Fooled by the number of re-uses, the first excavators at Tanis believed themselves to be at Pi-Ramsès, a site where they thought the Hebrews had been slaves to the Egyptians. Pierre Montet thus hoped to find evidence of the Exodus, of the presence of the Hebrews in the land of Goshen. (Genesis 47, 6, etc.).

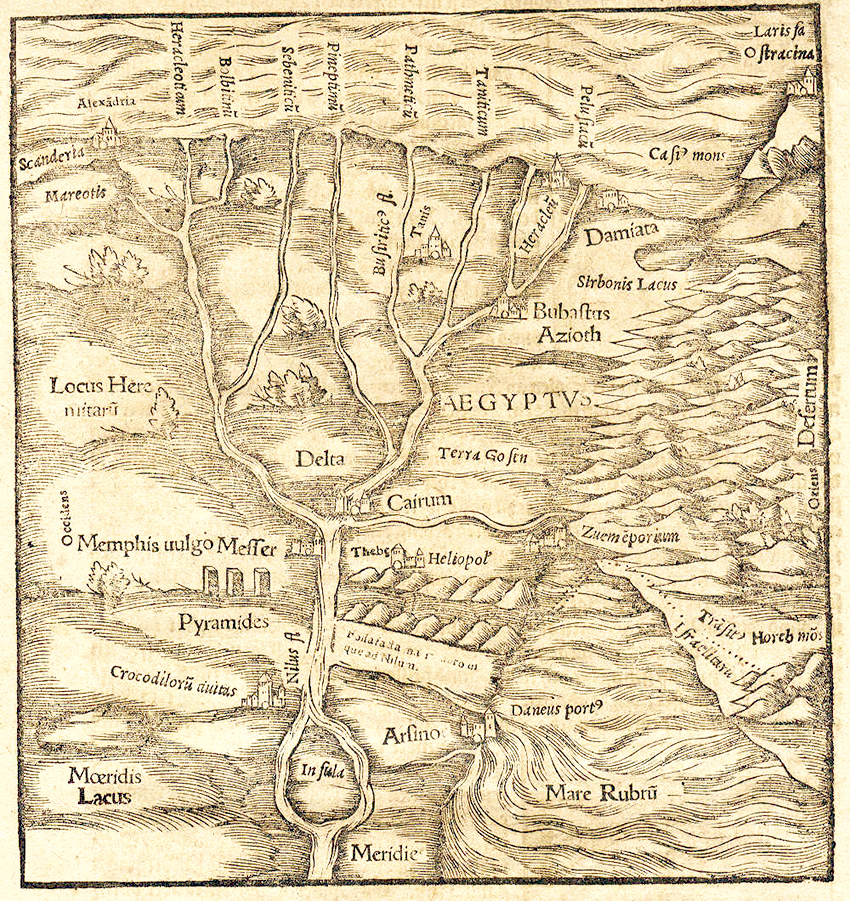

Image opposite: the oldest printed map of the Tanis site is by Sebastian Münster (1488-1552), a famous humanist scholar from Germany.

Courtesy of Jean-Jacques Desreux.

Tanis is also mentioned several times in the Bible under the name of Tsoan. (Numbers 13, 22 ; Psalms 18, 12 ; Isaiah 19, 11, etc.).

The links between Thebes, where Smendès I had left his mark in the temple of Karnak, and Tanis appear in the temple of Tanis dedicated to the triad formed by the deities Amon, Mut and Khonsu.

Excavations and discoveries

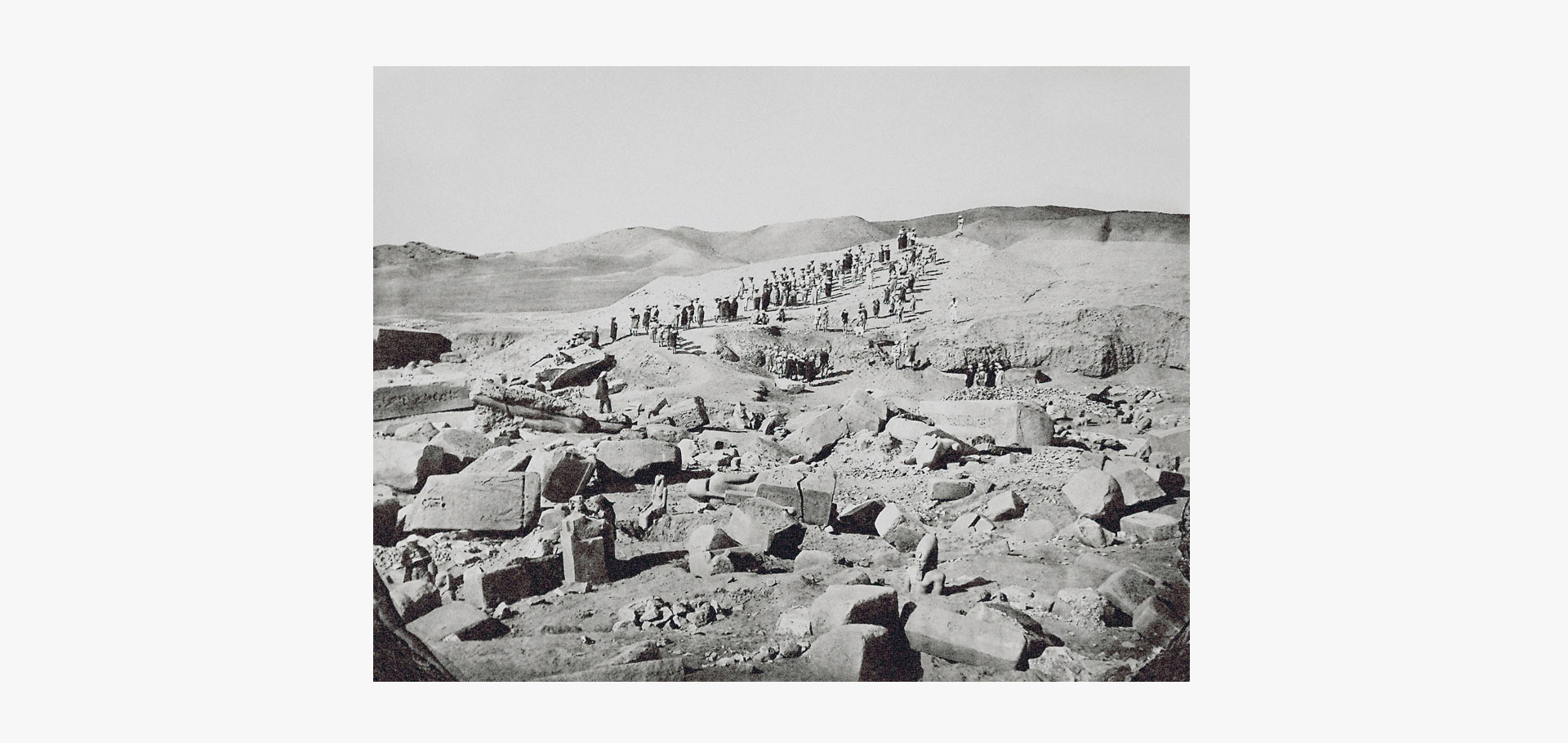

Image opposite: general view of the royal tombs at Tanis. Jon Bodsworth.

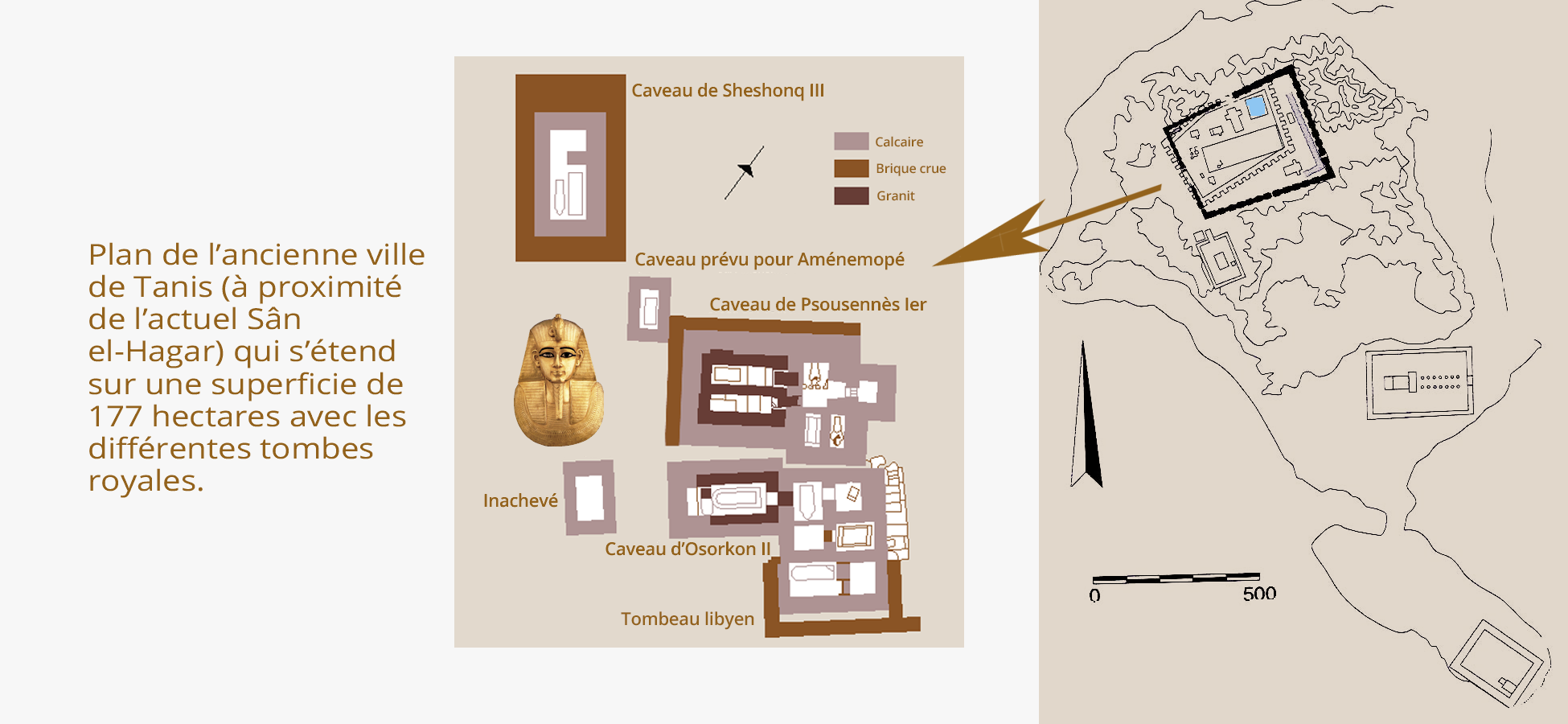

The central monument in the tell's northern zone is a large brick enclosure dating from the Ptolemaic period, measuring approximately 430 by 370 m. This wall was 15 m thick and probably at least 15 m high. Within this perimeter is another mud-brick enclosure dating from the reign of Psusennes I. All these enclosure walls include a temple dedicated to Amun. Outside the temple enclosure, near the south-west corner (see map), Pierre Montet discovered four funerary chambers, three of which are adorned with magnificent bas-reliefs painted in the name of Osorkon II.

The tombs had been looted, but the names mentioned on various documents are those of Pharaohs Osorkon I and II, Takélot II, Sheshonq III and Prince Hornakht, son of Osorkon II (Dynasty XXII). Continuing his excavations, P. Montet then entered another small funerary chamber decorated and inscribed with the name of Psousennes I, in which he discovered a silver coffin with a falcon's head. After opening the coffin, the deceased was revealed to be an unknown pharaoh of Dynasty XXII, Heqakherrè Sheshonq.

On January 23rd 1940, after dismantling the west wall of Osorkon II's tomb, P. Montet exhumed the vessel of Prince Hornakht, who had died aged 8 or 9, and his treasures, which had been partially spared by thieves.

Image opposite: a gold bracelet inlaid with hieroglyphic signs in colored stones, unearthed from the coffin of Psusennes I. ©

Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

King Farouk, faced with the urgency of the international situation, recommended to P. Montet the immediate opening of the chamber located to the south of that of Psousennès Ier. On April 16, the entrance was cleared, revealing to archaeologists the treasure of Pharaoh Amenemope (c. 993-984 BC), son and successor of Psusannes I.

These burials, some of which are located in underground areas, usually comprise several chambers built of limestone, granite or mudbrick. Access to these chambers is via a well. Some tombs contained several mummies, with granite sarcophagi that were often usurped. Silver coffins, gold mummy masks and jewelry (pectorals, bracelets and necklaces) are among the most remarkable finds in these tombs.

On the subject of exhumations in the years 1939-1940, Pierre Montet writes :

«The most dazzling collection of gold masks known to ancient Egypt [...] the series of vases fashioned in gold, silver and electrum is without equal».

Image opposite: the golden mask of General Oundebaounded. Egyptian Museum, Cairo, Egypt.

Excavations were interrupted by the outbreak of the Second World War in Europe.

Excavations resumed on April 15, 1945, on the ruins of ancient Tanis. P. Montet was once again at work, continuing his examination of the tomb of Psusennes I.

In 1946, architect A. Lézine analyzed the structure of the tomb and concluded that there must be an unknown chamber; indeed, the inviolate tomb of general Oundebaouded contains a treasure of a quality comparable to that of Psousennès Ier, of whom he was the principal dignitary.

This exceptional collection of gold and silver, part of which will be exhibited in the Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais in Paris in 1987, shows that despite the political weakening of Egypt, the court of Tanis perpetuated the splendors of the New Kingdom.

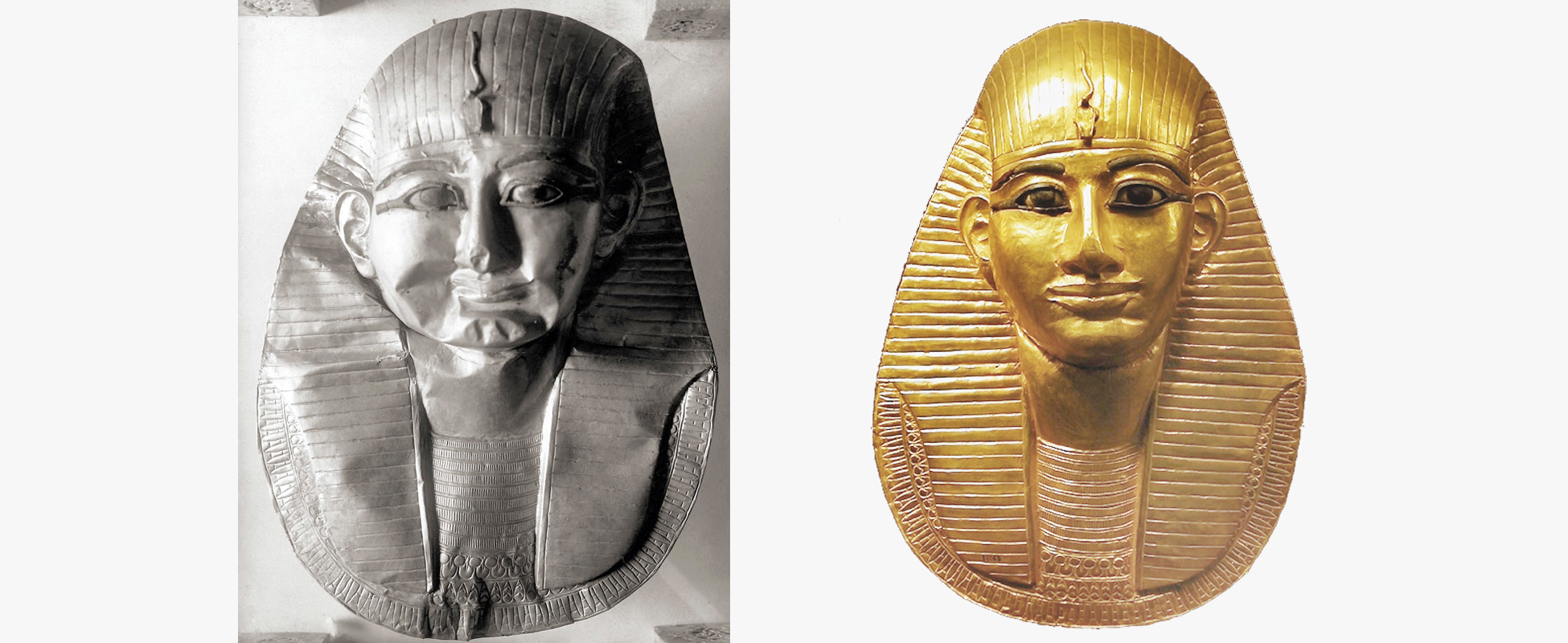

From left to right: the golden mask of Amenemope, son and successor of Psousennes I, at the time of its discovery.

The golden mask of Amenemope after restoration. Egyptian Museum, Cairo, Egypt © Société française des fouilles de Tanis.

The tomb of Psousennes I

The rich tomb of Psusennes I (c. 1039-991 BC), the greatest king of Dynasty XXI, is intact. To date, it is the only unearthed Pharaonic tomb to have completely escaped looting. His burial is attested with certainty by inscriptions on the walls of the burial chamber and by the foundation deposits of the sanctuary, located at the eastern end of the temple.

An imposing pink granite sarcophagus contains an anthropomorphic black granite coffin, which in turn contains a silver coffin. It later transpired that the sarcophagus had been used 170 years earlier for the funeral of Merenptah (c. 1212-1203 BC), 13th son and successor of Ramses II, in the Valley of the Kings.

On the mummy's face, of which little remains due to the high humidity and salinity of the site, is the magnificent gold mask under which we discover all the finery of a pharaoh. The sovereign is surrounded by the accessories destined to accompany him into the afterlife and an extraordinary array of solid gold ritual tableware: pectorals, amulets, bracelets and necklaces, prophylactic objects and insignia of power.

Image opposite: the solid gold funerary mask of Psousennes I at the time of its discovery in 1940 by P. Montet's team.

Image opposite: the solid gold funerary mask of Psousennes I at the time of its discovery in 1940 by P. Montet's team.

Image © Société française des fouilles de Tanis.

Psusennes I's wife, Moutnedjemet, who was also his half-sister, and one of his four sons and successor, Aménémopé, are also buried at Tanis.

The importance of this discovery can be compared to that of the tomb of the young king Tutankhamun in the Valley of the Kings, unearthed in 1922 by Howard Carter.

It has long been thought that Psusennes I was the pharaoh with whom the Hebrew king Solomon (c. 970-931 B.C.) sealed an alliance by marrying his daughter (1 Kings 3,1). Today's more precise dating suggests that it was Siamon (circa 978-959 BC) who, as a dowry, offered Solomon the city of Gezer, which he had taken from the Canaanites (1 Kings 9,16). A few items belonging to this pharaoh have come to light. A fragment of a stele found at Tanis shows Siamon preparing to kill an enemy, probably a Philistine. This may correspond to the pharaoh's raid against the Philistines at the time of the capture of Gezer. Siamon later had a courtyard and possibly a pylon (the second) built in the same area.

Tanis, which appears as a new city designed and built like a northern Thebes (without reaching the same scale), was also the capital of the pharaoh of Libyan origin, Sheshonq I (the Shischak of the Bible, c. 945-924) at the head of his army a daring raid we've already mentioned, who seized the treasury of the Jerusalem Temple and its palace (1 Kings 14, 25-26). Several of his personal jewels were discovered in the royal necropolis of Tanis.

Until the end of the Montet mission, the entire royal tombs area was actively surveyed.

From left to right:

- The golden mask of Psousannes I. Psousannes is depicted here wearing the nemes surmounted by the uraeus and a false beard; 49 cm high. Egyptian Museum, Cairo, Egypt.

- A 20 cm-high gold ewer bearing the cartouche of Amenemope, son and successor of Psusennes I. Egyptian Museum, Cairo, Egypt.

Some items of gold funerary crockery unearthed from the tombs of Tanis:

- A vase with 28 gadroons, 7.7 cm high. The neck bears the name of one of the daughters of Psousennes I.

- A 16 cm-diameter gold patera mentioning Psusennes I and another of his daughters. Egyptian Museum, Cairo, Egypt.

archaeological digs

archaeological digs

The Tanis site is one of the few archaeological sites in Egypt to have been in almost continuous activity for almost a century. The duration of these excavations reflects the historical importance of a city that was the capital of Egypt during the 21st and 22nd dynasties, and remained an important metropolis for almost a millennium and a half until the end of the Ptolemaic era.

Image opposite: from top to bottom :

Gold prophylactic pectoral of Psusennes I. Enhanced with enamel and colored stones. It measures 13 cm high.

The reverse side in chased gold. It is flanked by the sister goddesses Isis and Nephthys, charged with watching over the deceased. Egyptian Museum, Cairo, Egypt.

After the «discoverers» of the site, Père Paul Sicard (1707-1722), the geologists and mineralogists Dolomieu and Cordier (1799-1800), who in 1978 drew up an important, detailed and accurate description of the site, came the topographer Jacotin, who drew up a remarkably precise plan that was the only comprehensive cartographic base available to archaeologists until 1984. Then came the «antiquaries», Sir William Hamilton (1801), the French Consul in Cairo Bernardino Drovetti and Jean-Jacques Rifaud (1825). The latter unearthed eleven royal statues, of which only four were sold to B. Drovetti. Drovetti, who sold them to the Louvre and the Berlin Museum.

However, the first large-scale excavations were carried out by Auguste Mariette (1821-1881), between 1860 and 1868 (see image below). Brief but effective interventions were continued by the English archaeologist Sir Flinders Petrie from 1883 to 1886. He resumed his study of the Temple of Amun, drew up an overall plan (limited to the enclosure of Psusennes I) and numbered the main blocks to facilitate identification. This document remained the only one of its kind until 1990.

The Tanis site was extensively developed between 1929 and 1956 by Pierre Montet, in particular with the discovery of the royal tombs and their treasures.

P. Montet's twenty or so excavation campaigns on the site can be divided into three main periods:

- from 1929 to 1938: exploration of the northern zone of the tell in search of possible traces of Semitic influence and the legacy of the Hyksos.

- 1939 to 1946: the period when the royal tombs were discovered.

- 1947 to 1951: excavation of the Amun enclosure in search of new tombs.

After a few years' interruption, the excavations were resumed in 1965 under the direction of Jean Yoyotte (1927-2009), succeeded by Philippe Brissaud who, at the head of the Mission since 1985, created the Société Française des Fouilles de Tanis in 1988 with Jean Rougemont.

Today, the temple appears as a mass of column blocks, obelisks and statues from different periods, with inscriptions and decorative motifs. Some of these elements bear the names of pharaohs of the Old and Middle Empires (Cheops, Chephren, Teti, Pepi I, Pepi II, Sesostris I).

Image opposite: a gold bracelet bearing the name of Chechonq I. © Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

The enclosure of Psusannes I contains other buildings. Some of its blocks, notably belonging to a temple and chapel for the festival-sed of Chéshonq V, as well as a temple of Psammétique I, were reused by Nectanebo I to create the Sacred Pond and, still nearby, a temple of Khons-neferhotep. However, the foundations of the temples and their foundation deposits, as well as all the witnesses in place, date back no further than the 21st dynasty. The rulers of the 21st and 22nd dynasties simply built their capital with monuments taken from elsewhere, mainly from Pi Ramses.

Image below: One of the rare views of Mariette's excavations at the ancient site of Tanis, circa 1861 © Société Française des Fouilles de Tanis.

Find out more

TRUSCHEL Théo, The Bible and archaeology

Éditions Faton, 2010, Paris.

pp 116-119.

Numerous richly illustrated hors-texts present archaeological discoveries in Israel, Egypt, Iraq and Iran, and their sometimes controversial interpretations. They deal with the specific study of sites (Samaria, Mount Ebal, Tanis, Elephantine Island), certain stelae (Mesha, Tell Dan, Merenptah) and various exhumed objects (ivory grenade).

archaeological digs

archaeological digs