Bible, History, Archaeology

History,

Archaeology

Home >

The two silver rolls,

Ketef Hinnom or the treasure of Jerusalem

Introduction

The name Ketef Hinnom - the shoulder of Hinnom, in Hebrew - refers to an ancient necropolis at the foot of the ancient city of Jerusalem. In recent years, this site has yielded an exceptionally rich heritage of undoubted historical interest, particularly for the study of the Hebrew Bible.

excavations in the Ketef Hinnom valley

Image opposite: a general view of the Hinnom valley. © DR.

The historic city of Jerusalem is bordered by a narrow ravine, the Valley of Hinnom (or Gehenna, in French), which runs partially around the hill of Zion. It begins to the west of the ancient city, then heads south and east to join the small valleys of the Tyropeon and Kidron. This depression penetrates the limestone, forming rugged walls that surround the meadow floor. On the valley's south-western slope, a contemporary edifice has stood since 1927: the Scottish church of Saint-André, whose chevet overlooks the Hinnom valley.

Image opposite: detail of one of the caves in the Ketef Hinnom valley. © DR.

For a long time, the Hinnom valley served as a cemetery. One of these rock tombs was the site of a spectacular discovery.

The discovery of seven graves

In 1975, Dr Gabriel Barkay, an archaeologist at the Hebrew University of Bar-Ilan, spotted a number of artefacts in the Hinnom Valley that bore witness to past human occupation. He planned to carry out excavations, but with a limited budget, he employed volunteer labor provided by an archaeology club for young college students. With the agreement of Tel Aviv University, he opened an archaeological site on the land below Saint-André church.

Image opposite: fragment of a Byzantine church mosaic depicting a partridge amidst a bunch of grapes. bib-arch.org.

On the northern side of the hill, the forgotten remains of a Byzantine basilica were soon discovered. The majority of the building's stones had disappeared, but the bases of the walls were still visible, forming a nave, an apse, an entrance threshold and column bases. The interior of the building revealed fragments of a magnificent mosaic buried in the dust of the ground, one of which depicted a partridge feeding on a bunch of grapes amid vine shoots and leaves. Next to the Paleo-Christian church, a vaulted room served as a crypt, while another level revealed a fine assemblage of marble slabs in a variety of colors and shapes.

To which ancient monument did this edifice correspond? By consulting the available archives, the researchers made the connection with a lost church named Saint-Georges-hors-les-murs, which was destroyed during a Persian invasion in 614 AD.

Excavation of the basilica's basement uncovered older remains of hearths and vessels containing burnt human bones. These were attributed to the 10th Roman Legion, stationed in Jerusalem between 70 AD and the reign of Diocletian in the 3rd century AD.

Slightly below the basilica, a group of earlier tombs were cut into the rock and closed by large stone slabs. Most of them yielded a few coins dating back to the period of the Second Temple of Jerusalem, i.e. between 516 B.C. and 70 A.D. These may have been Judean tombs, where the dead were temporarily laid to rest before their final burial.

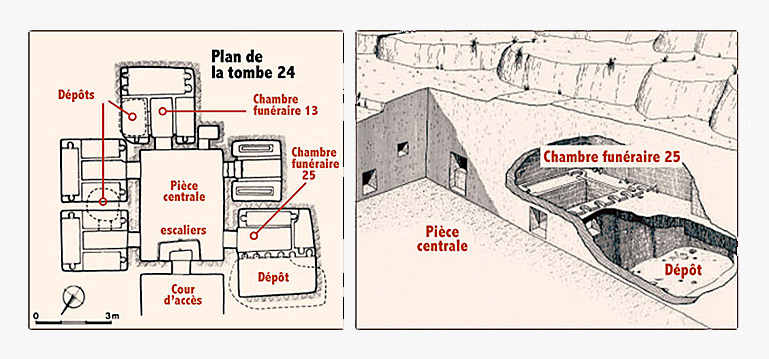

But the area that proved most interesting was a group of seven older tombs, dating back to the end of the First Temple period (7th/6th centuries BC). Subsequent quarrying had led to the collapse of the vaults, leaving the vaults exposed to the air. Their layout followed the classic pattern of Hebrew rock tombs of the period: a courtyard, a central room and narrow burial chambers with lateral benches on which the bodies were laid. (see the ossuary of James son of Joseph). Some of these benches were fitted with curious projecting ledges to serve as headrests for the deceased. Beneath several of these funeral benches, an empty, enclosed space was carved out, which must have served as a final repository for the bones several months after burial.

A chance discovery

Image opposite: Tomb N° 24 and its burial chamber in the Ketef Hinnom valley. Wulfran Barthélemy plan.

It was the central part of the chamber that contained the widest funeral bench, with six seats equipped with headrests. The child soon returned to Barkay laden with earthenware. He explained that, having finished his work, he had inadvertently broken the side wall of the funerary bench with a hammer, revealing the entrance to an obscure cavity.

Leaning over the gaping opening, the researcher saw a large volume of rubble from which a few antique objects seemed to be emerging in disarray. The vault was clearly a funerary repository that had been forgotten since antiquity, and had remained safe from looting.

A fabulous treasure

The contents of the tomb began to be carefully extracted and inventoried. Fearing that the affair might become public knowledge, it was decided to excavate with all speed. Teenage volunteers were replaced by students and professionals. As objects were uncovered, they were drawn, located, numbered, exhumed and cleaned.

Image opposite: entrance to tomb 25 © waynestiles.com

Mixed in with these precious pieces of jewelry was an abundance of pottery. It consisted of wine decanters, bowls, perfume bottles, oil lamps, carrot-shaped bottles and bag-like decanters. Particularly elegant was a kind of small amphora made of glass and decorated with yellow and blue stripes (see image below). The object must have been moulded around a sand core. The style of this ware made it possible to date the contents of the deposit, whose age ranged between the 7th and 6th centuries BC.

More innocuous artifacts included arrowheads, needles, blush sticks, bronze buttons, a knife and an iron chisel. An alabaster blush palette, four conical stone spindles and a series of fluted ivory cylinders with holes at the ends were also unearthed; the latter were nothing more than gripping handles attached to metal cauldrons to prevent burns.

Image opposite: the Palta seal and its script. bib-arch.org.

As is often the case with this type of object, the name Palta was probably an abbreviation. The full name must have been Pelatyah or Pelatyahu, a form including the name of the Hebrew god, Yahweh. The point to note is that this name is found in the Old Testament, and more specifically in the book of Ezekiel (11:1-13), where mention is made of a high official named Pelatyah, son of Benyah. Was he the same person? It's hard to say.

In all, a treasure trove of over a thousand objects was inventoried. 125 silver jewels, 45 arrowheads, 150 semi-precious stones, 6 gold objects, 250 terracotta vessels, the bones of 90 people, ivory, glass, earthenware, shells and carved bones made up the Ketef Hinnom treasure. Today, the contents of this vault represent the richest archaeological collection ever discovered in Jerusalem.

A small part of the treasure unearthed, from left to right: various items of jewelry, precious and semi-precious stones, an arrowhead, a small amphora, a gold ring, etc. bib-arch.org.

Two rolls of silver

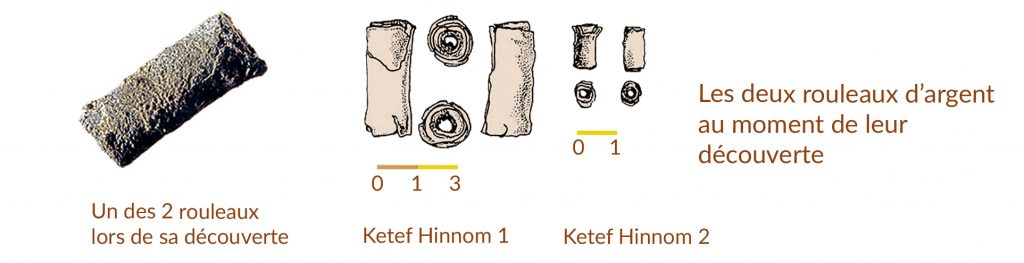

However, this exceptional find was nothing compared to the one awaiting the archaeologists, which was to turn out to be of an altogether different historical significance. While methodically searching the interior of the deposit, a student spotted a small greyish cylinder that looked like a cigarette butt. It was a very thin sheet of silver rolled up on itself, and its inner face was suspected of bearing an inscription in the manner of ancient book scrolls. A second silver cylinder was discovered when the floor of the deposit was sieved. Smaller than the first, it was also likely to conceal an inscription.

To find out, the two objects had to be unrolled as carefully as possible to avoid any damage. As the cylinders were heavily corroded and riddled with cracks, the operation was a risky one. They were entrusted to a local specialist from the Israel Museum, Joseph Shenhav, who was charged with finding an appropriate method for this delicate task.

The technique adopted consisted in gradually applying a special acrylic glue to the silver rolls, consolidating them as they were unfolded. The two objects were finally coated with a protective film and placed between two glass plates. Three years after their discovery, the surfaces of the rollers had become clearly visible, and microscopic examination confirmed that they were covered with numerous signs of writing.

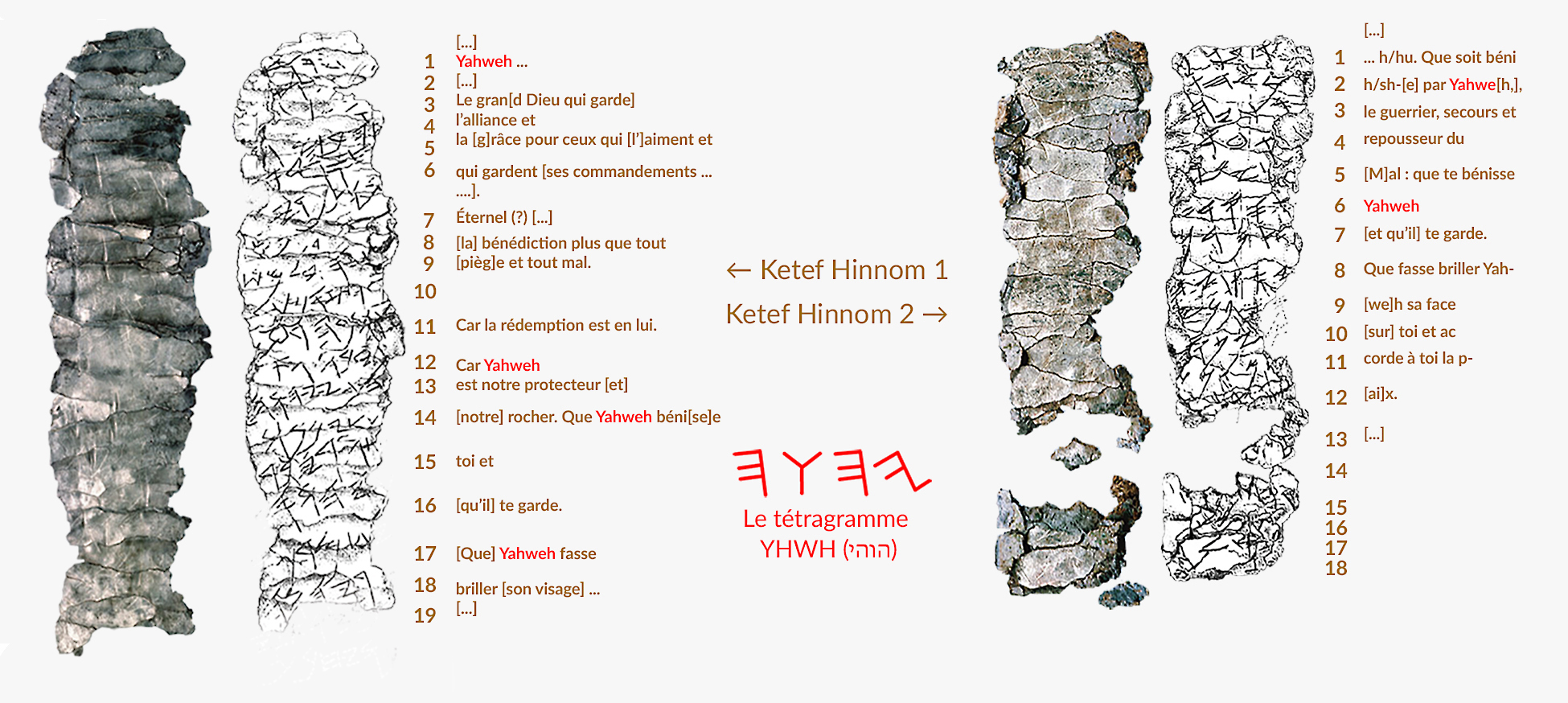

Deciphering these fragmentary inscriptions was not going to be easy. The characters were incised on the leaves in strokes as fine as hairs, traced in an ancient form of Hebrew script, Paleo-Hebrew, which predates square Hebrew. On examining the unfolded leaves, Gabriel Barkay nevertheless recognized a well-known association of letters: YHWH, i.e. the tetragrammaton that expressed the name of the Hebrew god, Yahweh.

Did these inscriptions have a sacred character? It was found that the divine name appeared several times on the same sheet (see image below). The paleographer Ada Yardeni, who studied them, made the connection with a short extract from the Bible which also contained the triple occurrence of Yahweh's name: the «priestly blessing», a formula used in Israelite ritual (Numbers 6:24-26). The specialist realized that the connection worked, and was able to decipher the leaves by following this thread (see the translation proposal in the table below).

The result of the decipherment was a variant of the biblical verses that went like this (Numbers 6:24-26):

«May Yahweh bless you and keep you. May Yahweh make his face shine upon you and grant you his grace. May Yahweh turn his face toward you and give you peace.

In addition, the first scroll of Ketef Hinnom also included part of verse 9 of Deuteronomy chapter 7:

«Know therefore that only Yahweh your God is God, the faithful God who keeps his covenant faithfully to the thousandth generation of those who love him and keep his commandments.».

The two silver scrolls were probably amulets, whose function was to bless and protect their owners. Their hollow shafts could be fitted with strings so that they could be worn around the neck.

A little-discussed dating

Based on the shape of the incised letters and the rest of the tomb's contents, the researchers dated the scrolls to the late 7th century B.C. These results were published in 1989, prompting some doubts among other scholars. But further study of the letterforms, using state-of-the-art imaging and digital processing techniques, confirmed the age of the scrolls.

This work had implications for another major ongoing controversy, that of the age of the Bible's composition. When were the books of the Torah written? Although tradition traces them back to Moses, many scholars today date them to around the 7th century BC. This is roughly the age given to the silver cylinders. Admittedly, the two amulets do not prove that the Bible already existed in their time, but they do suggest that the formulation of certain passages of Scripture had already taken shape.

The two silver scrolls have helped refine our understanding of ancient Jerusalem and the context in which the sacred texts were written. Today, they are the oldest known documents related to biblical content, predating the famous Dead Sea Scrolls by at least four hundred years. Ketef Hinnom's exceptional heritage is now preserved in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

Wulfran Barthélemy