Bible, History, Archaeology

History,

Archaeology

Home > New Testament >

The canon of Scripture

New Testament

In the first phase of Church building, orthodoxy was not a given; on the contrary, there was a multiplicity of interpretations and polemics, so much so that the need for a «canon» appeared at the end of the 2nd century, in order to fix texts and doctrine.

The relationship between orthodoxy and heresy in the first centuries of our era is extremely complex. The founding event, the person and work of Christ, is unique, but the interpretations to which it gives rise differ according to the milieux and cultures involved. Early Christianity was not one, but many and varied. The various currents were not heretical, nor orthodox, since these notions were not defined, but it became necessary to establish the dominant doctrine that would become orthodoxy at the end of the 2nd century.

The disappearance of the first witnesses

Image opposite: reconstruction of a scene depicting a disciple reading a Gospel page © DR.

As for the apostles Paul and Peter, they were undoubtedly victims of Nero's policies towards Christians after the burning of Rome around 64. The apostle John, for his part, died of old age in Ephesus under the emperor Trajan (according to Polycrates of Ephesus or Irenaeus of Lyons). By the end of the first century, all direct witnesses to Jesus had disappeared.

Which churches?

It was during this period that various attempts were made to give a stable form to the tradition (often still oral) of the words and deeds of Jesus. These attempts were undertaken in the main Christian churches of the time, those attested by sources up until around 100 AD.

Image opposite: «Your word is a lamp to my feet, a light to my path». Psalm 119:105 © Grzegorz Zdiarski.

The churches of Asia form another group (Laodicea, Miletus, Pergamum...), including Ephesus, a major center of Paul's activity, where the «Pastoral Letters» are said to have been written. Its bishop, Onesimus, may well have been the fugitive slave of the Epistle to Philemon; it was also the site of the apostle John's activities. In Greece, we find the churches of Philippi and Thessalonica, as well as Corinth, which in the 2nd century was a center for the production and circulation of various writings. Finally, there are unspecified sites in the various provinces of present-day Turkey. We also don't know who founded the church of Alexandria (legend has it that it was founded by Mark), but perhaps its schools were initially the most important. Finally, there's the Church of Rome, which appeared in the 40s and, while it doesn't yet claim to be the head of the Great Church (the Roman Catholic Church), it is the capital of the Empire and, as such, attracts many protagonists who open philosophical schools there. Marc was written there.

What are the texts from this period?

What are the texts from this period?

Paul is very present in early Christianity, thanks to his abundant correspondence with the churches he founded or visited (this is not the case with the other missionaries, whose writings are certainly pseudepigraphic); after his death, his Letters continued to circulate in the Pauline churches, they were collected and most were accepted as authentic. They represent a seminal testimony.

Apart from this very special case, memories were transmitted in separate units: a «saying» or a group of sayings on a given theme, a miracle or a group of miracles... collections of Sayings were compiled (such as Source Q, a collection of texts from which the writers of the Gospels drew inspiration, the existence of which is probable but not certain); there are also small groupings, such as the one inserted in the Didache (doctrine of the twelve apostles; first decades of the 2nd century; see (below) the paragraph on the establishment of orthodoxy).

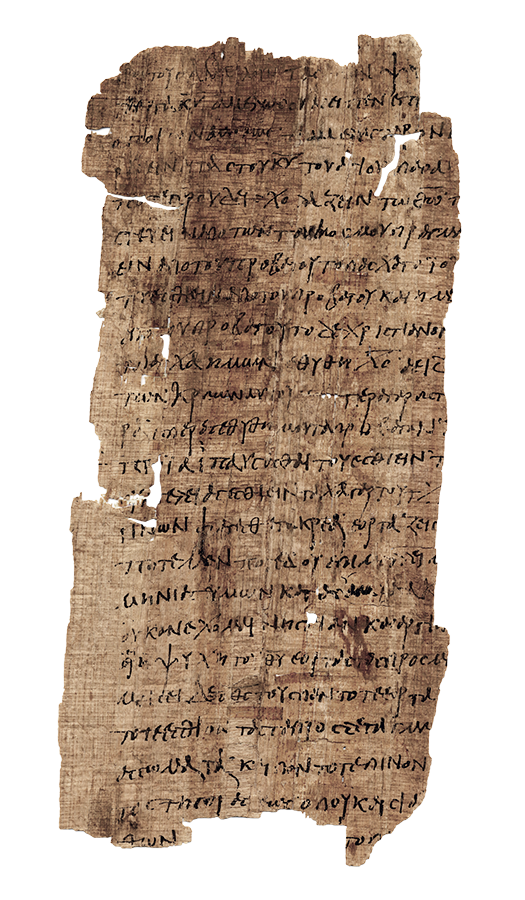

Image opposite: Homily on John's Gospel or Paul's Epistle to the Corinthians. Col III. H. 23.8 cm; W. 11 cm. Inv. 828 verso; Origen ? Pierre Bouriant 3; vH 693.

Institut de Papyrologie de la Sorbonne, Paris.

Initially, there seems to have been only one relatively long narrative, that of the Passion, which was formed very early on, the earliest being that of the Gospel of Marc. The three Synoptic Gospels provide an overview of the life of Jesus: the Gospel of Marc (circa 68/70, written in a place difficult to specify) will dominate the entire history of Christianity, that of Matthieu (circa 70, written in Jerusalem or Antioch?) and that of Luc (The Acts being quickly separated from the Gospel); the Gospel of Jean dates from the end of the 1st century, it assumes that the other three texts are known, and focuses on Jesus' speeches and proclamations.

«As Jesus walked along the Sea of Galilee, he saw two brothers, Simon, called Peter, and Andrew, his brother, casting a net into the sea; for they were fishermen. He said to them, »Follow me, and I will make you fishers of men. Immediately they left the nets and followed him.... " Matthew 4:18-20 © A. Lukasic.

Apocryphal« texts (meaning hidden)

Apocryphal« texts (meaning hidden)

The Gospels were finished when the apocrypha began to multiply. For some of them, the gap is small but decisive: they come second in time and expression, at the end of the 2nd and 3rd centuries. There are generally three groups of apocrypha: the archaic Gospels, the fictional Gospels and the Gnostic Gospels. The earliest of these originated in Judeo-Christian circles, but only a few fragments are known to have been cited by the Church Fathers. The second group tells a «story», emphasizing details that are omitted elsewhere and embellish the life of Jesus. This is where we find the legend of the ox, the donkey and the grotto of the nativity, the childhood of Jesus, his sojourn in Hell... they also shaped the essence of Marian piety (Mary's childhood, presentation in the Temple, perpetual virginity...) the oldest text is the Gospel of James and dates from the 150s. Finally, the Gospels of Gnostic inspiration are collections of the words of Jesus after his resurrection, addressed to selected disciples, with mysterious and «hidden» allusions. This is the case of the Gospel of Thomas, built up by successive additions around logia The Gospel according to the Hebrews is attested at the end of the 2nd century, but only a few fragments remain, including the account of the appearance of the risen Jesus to his brother James, making him the referent of the Jerusalem community. The late 2nd-century Gospel of Judas, discovered in Coptic and dated to the 3rd century, is also part of the Gnostic movement.

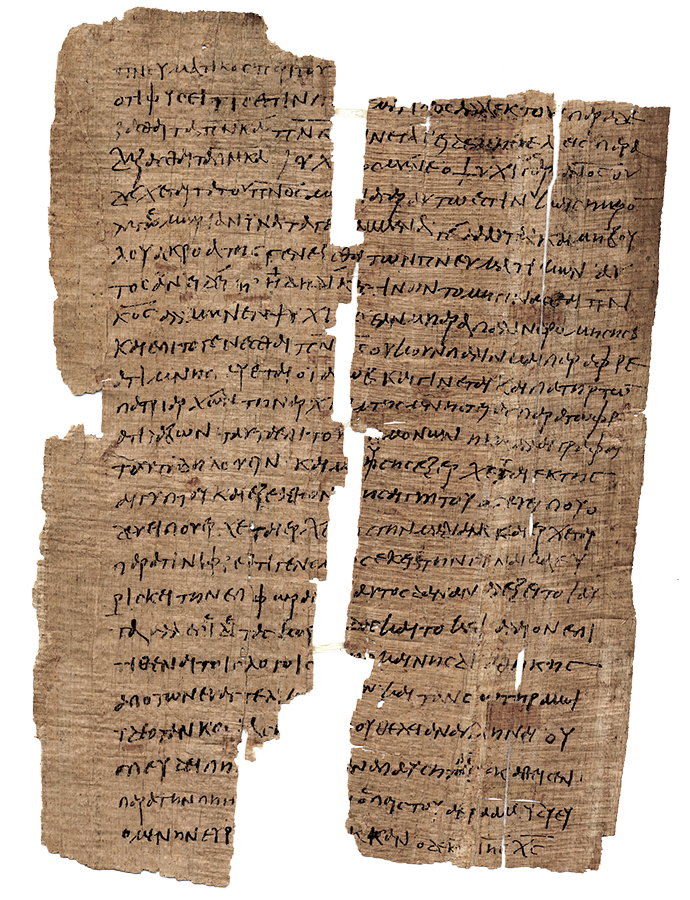

Image opposite: Paul's Epistle to the Corinthians. Col IV. H. 25 cm; W. 18.4 cm. Inv. 828 verso; Origen ? Pierre Bouriant 3; vH 693 © Institut de Papyrologie de la Sorbonne, Paris.

There are therefore a number of heretical currents that emerged during the 2nd century, the best-known of which are that of Valentinus and his «Gospel of Truth» (a text found in its entirety, transcribed in Coptic and dated 140), which insists on a fundamental dualism; he came to Rome and founded a school there before being excommunicated; the same is true of his contemporary Marcion: born in Pontus, who came to Rome and was excommunicated like him, he advocated a form of dualism that rejected the Old Testament, accepting as Scripture only Paul's Letters (with the exception of the Pastorals) and Luke's Gospel, purged of all Jewish references.

Establishing orthodoxy

Some episcopal letters give an account of controversies in the field; for example, when Marcion had completed his work of perfecting the Scriptures according to his criteria (between 139 and 144), he presented it to the Church of Rome at a hearing before the community; his interlocutors were certainly presbyters, responsible for preaching; his demonstration provoked a severe rebuttal. On the other hand, many bishops got involved, going out into the field and organizing meetings; these were not reserved for experts only, but for all the faithful who wished to attend; local debates were therefore widely open and gave rise to the writing and circulation of a whole literature (pastoral letters, memoirs and libels).

The need for a «canon» or «Rule of Truth», designed to fix the most important aspects of Christian tradition, appears in bishops' correspondence and treatises on heresiology at the end of the 2nd century. In the sense of a selection and collection of normative texts, this was an unprecedented need (the canon of the Hebrew Scriptures is indeed later).

The 2nd century saw the emergence of the idea of orthodoxy, with reference to the apostles and their writings. The true understanding of the Scriptures is that given by the apostles, who transmitted it to the communities and the leaders they established: the episcopes or presbyters (a term that seems equivalent to speak of overseers/administrators). Indeed, Acts attributes to Barnabas and Paul the institution of presbyters in the churches they founded (Acts 14:23) and, according to the same text, a council of elders (prebyteroi) headed the Jerusalem church. These figures, appointed by the apostles, are the guarantors of the correct interpretation of the texts. Their testimony is preserved in the writings they left and in their preaching, which is intended to be nothing other than a faithful repetition of the original message. One example is Polycarp, bishop of Smyrna, trained by the apostle John.

However, during the 2nd century, collegiate leadership gradually disappeared in favor of a mono-episcopate, now the guarantor and custodian of the «deposit of faith». This evolution is clearly visible in a text such as the Didache. This is a collection of ethical, liturgical and ecclesiastical disciplinary norms that was probably drawn up in the Antioch region of Syria, and completed in the first decades of the 2nd century. The text teaches us that episcopes and deacons were taking the place of prophets and doctors as holders of power in the Church (not without resistance, as shown by the charismatic movement initiated by Montan). The Didache is presented as a set of traditional and correct teachings that should serve as a model, hence its title: «Teaching of the Twelve Apostles». According to this analysis, heresies come after orthodoxy, of which they are a deviation. This was an attempt to resolve the problem of the plurality of theologies and practices, which was becoming more acute.

How to recognize Orthodox churches and texts?

As far as the texts are concerned, it's their antiquity that guarantees their authenticity; as we've seen, first-century churches preserved texts, recopied them and circulated them.

But how can we be sure of their interpretation? This is where the notion of apostolic succession comes into play. The first witness to this normative criterion was Hegesippus (circa 150; quoted by Eusebius of Caesarea); during his visits to numerous churches, he was led to list the bishops who had succeeded each other since their foundation by an apostle, this uninterrupted succession being the guarantee of orthodox teaching. Letter from Clément from Rome to the Corinthians presents the episcopes as successors to the apostles for the first time, making spiritual power sacred. On the other hand, a number of Episcopalians, the Apologists, who promoted Christianity in the face of Roman power, also defended «true doctrine» against heresies (such as Justin, Tatian, Clement of Alexandria, Tertullian, Irenaeus...). The pastoral letters they wrote, which circulated among the churches, helped to establish orthodoxy among the faithful.

In the end, therefore, during the 2nd century, the various communities each selected the texts considered to be authentically apostolic, but also the most ancient. Apostolicity and antiquity were the two criteria used. Remarkably, this choice was more or less the same for all the major churches of Christianity at the time, with some hesitation between the Apocalypse of John or the «Shepherd of Hermas» (suite of revelations, composed around 140), the inclusion or otherwise of some of the Epistles of Paul or Jude. We can cite the codex of the Martin Bodmer collection (dating from the early 3rd century), which brought together in this order the Gospels of Matthieu, Jean, Luc and Marc as well as Acts of the Apostles.

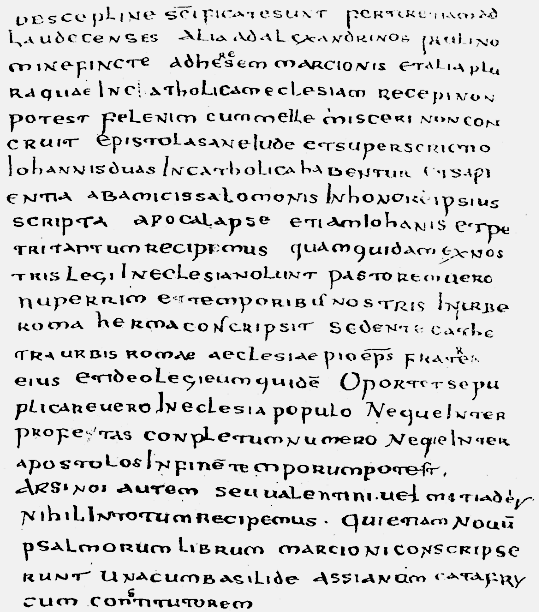

Image opposite: the Muratori fragment (detail) is one of the oldest texts to set out the (almost) complete canon of Scripture. Composed in the 2nd century, probably in Greek, it was translated into Latin around the 4th century. Public domain.

Image opposite: the Muratori fragment (detail) is one of the oldest texts to set out the (almost) complete canon of Scripture. Composed in the 2nd century, probably in Greek, it was translated into Latin around the 4th century. Public domain.

On the whole, the New Testament is the same everywhere, which is all the more remarkable given that there was no overall decision, no authority that would have imposed this approach in the second half of the 2nd century. However, we cannot precisely date the appearance of the New Testament as an organized book with a stabilized text; one possible landmark is the so-called «Muratori canon», a list of books drawn up in Rome between 165 and 185, but it is impossible to say whether it is a point of departure or arrival for composition.

The Canon of the New Testament, thus formed, was to serve as the standard for orthodoxy: any group that rejected all or part of the Scriptures (e.g. Gnostics, Marcionites...) was outside orthodoxy. This did not prevent the emergence of new heresies over the following centuries, but it did make it easier to denounce and reject them.

In 393, the Council of Hippo listed the 27 books that make up the New Testament canon.

Find out more

- Ancient Christianity (1st - 4th century). Paul Mattéi, Éditions Ellipse.

- How Christians became Catholics (1st - 5th centuries). Mr Fr. Bazlez, Éditions Tallandier.

- The birth of Christianity, how it all began. Enrico Norelli, Coll. Folio Histoire.

What are the texts from this period?

What are the texts from this period?

Apocryphal« texts (meaning hidden)

Apocryphal« texts (meaning hidden) Image opposite: the Muratori fragment (detail) is one of the oldest texts to set out the (almost) complete canon of Scripture. Composed in the 2nd century, probably in Greek, it was translated into Latin around the 4th century. Public domain.

Image opposite: the Muratori fragment (detail) is one of the oldest texts to set out the (almost) complete canon of Scripture. Composed in the 2nd century, probably in Greek, it was translated into Latin around the 4th century. Public domain.