Bible, History, Archaeology

History,

Archaeology

Home > Artifacts > AT artifacts >

Hammurabi's code of laws

Introduction

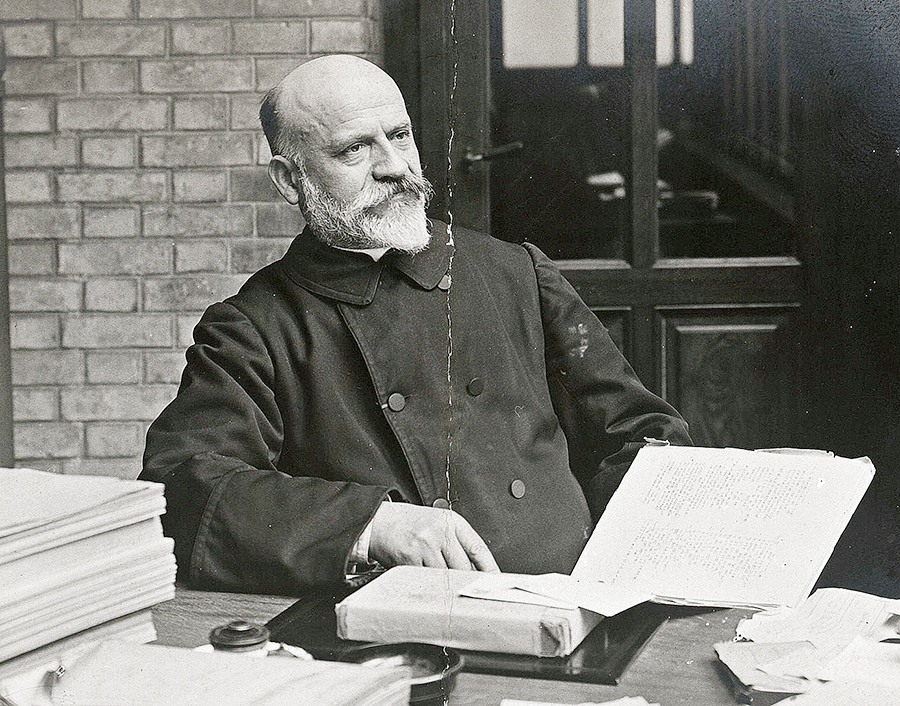

Reverend Dominican Father Jean-Vincent Scheil (1858-1940), French archaeologist and Assyriologist. Famous for translating the inscriptions on the stele of the Code of Hammurabi, in Iran. Public domain image.

Hammurabi's work as a legislator made him one of the most famous figures of the ancient East. The text was translated as early as 1902 by Father Scheil.

Image opposite: an inscription of Hammurabi's name incised on a stone. On the right, the original piece, on the left, the transcription.

New York Museum of Art (MET).

Description

The stele, now on display at the Louvre, is carved from a block of diorite, a stone of particular value due to its hardness and remote origin (present-day Sultanate of Oman), which guaranteed the integrity of the monument and the sovereign's image.

Image opposite: Hammurabi's code of laws, with the Louvre Museum in the background. 2.25 m high and 1.90 m in circumference. Images and editing by Théo Truschel.

Hammurabi, for his part, wears the high-brimmed bonnet of Sumerian tradition, and a long, draped robe with barely outlined pleats and no embroidery, but with a braided border. He stands in a hieratic attitude, not touching the emblems handed to him by the god, but raising one hand in front of his mouth - the classic attitude of the faithful in prayer in Mesopotamia, already seen on the seal of Goudéa, prince of Lagash. The conventional rendering of the figure does not allow us to see a personal portrait of the king.

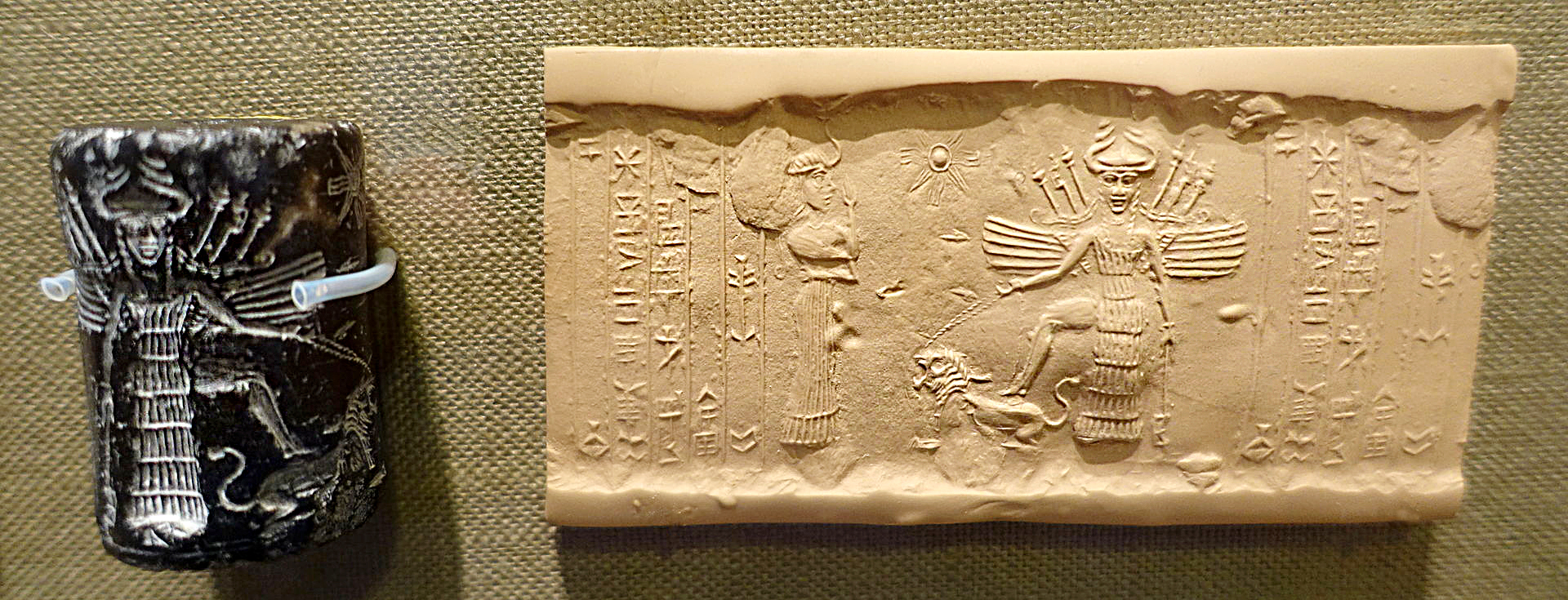

The reign of Hammurabi saw the eclipse of the old agrarian divinities of Sumer, whose cult was linked to fertility, in favor of astral divinities such as Shamash in Sippar, Ishtar, goddess of love and war identified with the star Venus, Adad the god of storms and Marduk in Babylon.

Image opposite: the top of the stele representing Hammurabi, on the left, and facing the king, Shamash, the personified sun god, patron of justice. Musée du Louvre, Paris. © Théo Truschel.

Shamash is the god of the sun, and the original ideogram representing him was a rising sun between two mountains. Gradually, he appears in human form and becomes the guarantor of equity and social justice, which is why the king has himself represented in his presence, as he says in the prologue to the stele.

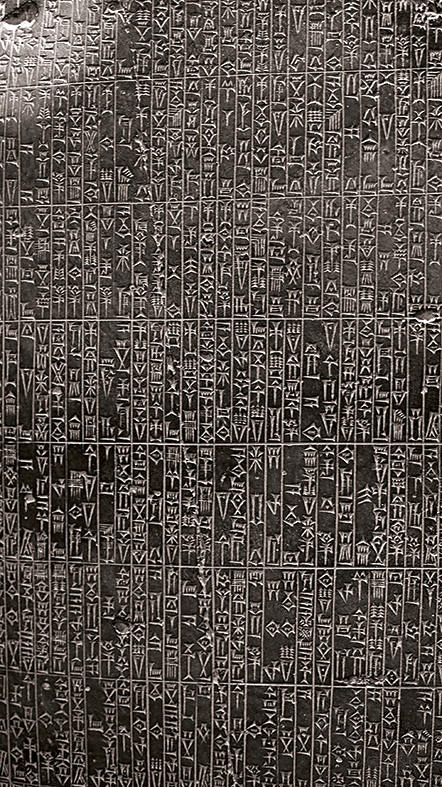

The rest of the stele consists of a 28-column inscription of 282 «articles of law», or rather sentences formulated in a legal manner. It includes a prologue and an epilogue praising the king and the articles of law. The text is not written in Sumerian, but in the language of the Semites of Akkad, Akkadian having become the language of diplomacy in the 2nd millennium B.C.; the writing is cuneiform, with extremely meticulous handwriting. The stele was probably erected in Sippar, city of Shamash, sun-god and god of justice. This type of document is not the oldest, since a collection of court rulings from Ur-Nammu (21st century BC, founder of the 3rd dynasty of Ur) and the code of the king of Isin Lipit Ishtar, written in Sumerian (19th century BC), have been found..

Various illustrations of scenes from the Akkadian and Sumerian empires: king in chariot, lion and warrior, battle scene. matrioshka 1549413956.

The prologue

It is a hymn to the glory of the king, celebrating his accession to power and his achievements:

«When the sublime An, the king of the gods, the master of the heavens and the earth, the one who sets the destinies of the Land, had assigned to Marduk(...) omnipotence over the whole of the people(...), when they had pronounced the sublime name of Babylon and made it preponderant in the four corners of the world (...), then it was my name, Hammurabi, pious prince who reveres the gods, which An and Enlil pronounced to ensure the happiness of the people, in order to bring about justice.), then it was my name, Hammurabi, pious prince who reveres the gods, that An and Enlil pronounced to ensure the happiness of the people, to bring justice to the land, to eliminate the wicked and the perverse, to prevent the strong from oppressing the weak. » (Trans. after M. Roth).

This bronze and gold bowl holder features a group of three ibex standing on a pedestal decorated with two deities holding an offering vessel (2000-1800 B.C.). Musée du Louvre. Image © Théo Truschel.

The prologue continues with the king's military successes and the impressive list of cities he conquered. When Hammurabi (c. 1792-1750, fifth king of the Amorite dynasty) came to the throne of Babylon, Mesopotamia was in turmoil due to rivalries between the various cities. After consolidating his power in Babylonia, he seized the royal cities of Larsa, Eshunna, Mari and Ashur; by the end of his reign, his empire encompassed the entire Tigris valley and the Euphrates as far as beyond Habur, thus reconstituting the unity of Mesopotamia.

In the text of the Annals of his reign, in the 31st year, he can thus declare himself master of Sumer and Akkad, and also king of the Four Regions, demonstrating his vocation to universal monarchy. The enumeration of cities is accompanied by a personalized eulogy, an opportunity for the king to extol his merits and his respect for the local divinities that each contributed to his power. First mentioned are the major religious centers of Nippur, Eridu and Babylon, then the great cities dedicated to the worship of astral divinities such as Ur (god of the moon: Sin), Sippar and Larsa (Shamash), Uruk (Ishtar), then the other conquered cities including Mari, Akkad, Assur and Nineveh. Most of the major Mesopotamian cities were also conquered.

A cylinder with its imprint from the Akkad period featuring the warrior goddess of love Ishtar in the center, winged and carrying weapons on her back, accompanied by her attributes, a lion on a leash and the eight-pointed star. Museum of the Oriental Institute of Chicago. Image © Daderot.

The code

The 282 articles are not, strictly speaking, laws as are the articles of our Civil Code or Penal Code, but royal decrees drawn up as follows «a specific treatise on the art of judging».» (Jean Bottero). This is a collection of concrete cases concerning various aspects of social, administrative and economic life, covering a wide range of issues: theft and infringement of property rights, property management, economic and financial affairs, marriage and family law, assault and battery, remuneration, the situation of slaves... The collection does not form a homogeneous whole, with gaps, repetitions and sometimes even contradictions. It needs to be seen in the context of a society where oral customs were the rule, while the written word was rarely used. Its importance stems from the fact that the king wished to unify existing traditions and legislation by applying his «laws» to all conquered territories, which he wished to subject to the same rule. This stele is thought to have been found in several cities, and three copies have been found, not counting copies on clay tablets. The presentation is casuistic: if X is in such and such a situation, then such and such a solution applies.

§ 26 If a soldier (…) who had been ordered to take part in a royal expedition did not go, or, having hired a mercenary, sent him in his place. (…) will be put to death and his denouncer will take away his house».

§ 64 : «If a man has given his orchard to an arborist to make it bear fruit, the arborist (…) will deliver two thirds of the production to the orchard owner and will take one third himself».»

§ 128 : «If a man has taken a wife but has not drawn up her contract, that woman is not a wife».

§ 132 : «If a married woman has been singled out because of another man, but has not been caught sleeping with another man, she will have to dive into the river-god for her husband. 1 ».

§ 196 If a man has put out another man's eye, we will put out his eye«.

§ 200 If a man has knocked out another man's tooth, we'll knock out another man's tooth.

§ 282 «If a slave has said to his owner «you are not my owner», his owner will prove that it is indeed his slave, and he will cut off his ear».

(Translated by B. Lafont after M. Roth).

Image opposite: the text (detail) of the 28 columns comprising the 282 «articles of law» is engraved in the language of the Semites of Akkad. Musée du Louvre. Théo Truschel.

In addition to the information it provides on the jurisprudence of the time, this code also gives us an insight into the structure of society. The population was divided into three classes: the wealthy, the common people and the slaves. Each of these categories was assigned proportionate rights and duties: the better-off were better protected, but had heavier duties to pay; the common people were free men, but offenses against them were less punished; the least favorable status was that of slaves.

§ 26 Free men were directly answerable to the king, and were given all state posts, but they could also have an independent profession (craftsman, doctor...); the bulk of this population was made up of farmers, subject to dues in kind and corvée. They also made up the bulk of the king's armies, and in exchange for their service they often received a benefit (ilku) in the form of plots of royal land to cultivate; these soon became hereditary.

Opposite: cuneiform writing takes its name from the wedge-shaped lines impressed by a calamus on soft clay. From the Latin cuneus meaning «corner». Public domain.

§ 128 and § 132 Marriage and family law are based on monogamy, with the validity of marriage based on a contract. The wife receives a dowry from her father (considered an advance on the estate) and may enjoy it freely; she may also sue in court or exercise a profession. But the husband has the legal right to take a secondary wife or a slave-concubine, often when the primary wife is sterile. This practice was common in the Ancient Near East, and can be found, for example, in the stories of the patriarchs of the Old Testament. However, they do not occupy the same position as the principal wife, and the latter may sell them into slavery if they seek to be equal to her.

Another practice, already attested by numerous Mari texts, is that of the’trial by ordeal. It consists in waiting for the river-god to deliver a verdict, considered infallible, on a case submitted to his justice. The ordeal involves immersion in the river, a plunge «into the heart of the god», at the risk of drowning. This is the case of the married woman suspected of adultery. The woman who drowns is «married» by the river, her guilt recognized, and the one who escapes is exonerated. 1.

1. Ordalia Judicial trial used to establish a right or confound a guilty party in the absence of proof or confession. It took place in the deified River (Mesopotamia...).

The relationship with the Mosaic Law

§ 196 and § 200 In two chapters, we also note the appearance of what would become «the law of retaliation», even if the meaning here on this stele is that of punishment, whereas in the biblical text the idea is that of reparation and compensation comparable to the harm suffered.

The exhumation of this monument represented a major discovery for biblical scholars at the time. Some critics had argued that writing and legislation were unknown to the men of that period of history.

This discovery proved that both were already well known even before the time when Moses was said to have lived. Secondly, there are similarities, sometimes even striking parallels, between some of Hammurabi's laws and those contained in the Book of the Covenant.

Image opposite: a procession of a Torah scroll (Seder Thora) during a festival in front of the kotel in Jerusalem. Public domain.

For example, in the law regulating blows to a person, the Code of Hammurabi states (article 206):

«If, during a quarrel, a man accidentally hits another man with a stone or his fist, and forces him to go to bed, he will pay him the loss of his time and the doctor's expenses.»

In Exodus 21:18-19:

«And when men quarrel, and one strikes the other with a stone or fist, and the latter, without dying, falls bedridden, if he can get up and go outside with his cane, the one who struck will be acquitted. He will only have to pay his unemployment and look after him until he recovers».

The similarity between these two articles and others has led some critics to put forward the idea that the laws of Moses contained in the Bible were largely derived from the Code of Hammurabi. However, on closer examination, the vast majority of scholars have abandoned this theory. They discovered that, in ancient times, many countries had their own codes of law. Some were even older than the Hammurabi stele. The universal conscience that finds its way into the hearts of men has long since made it clear that good and evil exist, and that the best way to treat men is to uphold justice.

The Mosaic Law is far superior to the Code of Hammurabi and other ancient codes of law in terms of its high moral and spiritual standards, its emphasis on the importance of God's relationship with man, its demand for more humane treatment of slaves, and the great value it attaches to human life.

Hammurabi's Code was essentially civil and criminal in nature, with reparation differing according to the victim's social class; the Mosaic Law was more generous with servants and handmaidens, with an added moral and religious aspect.

In this sense, it is unique compared to other codes of all times.

The epilogue

The epilogue

The stele is undoubtedly a propaganda tool in which the king himself celebrates his justice; his aim is for royal justice to be recognized and applied everywhere.

«Let the aggrieved man who has a lawsuit go before my statue of «King of Justice», read my inscribed stele, listen to my most precious words and let my stele reveal his lawsuit to him, so that he may see the sentence that concerns him and be appeased.». (Translated by D. Charpin)

Image opposite: votive statuette of a kneeling worshiper, Lu-Nanna, dedicated to the life of Hammurabi, possibly from Larsa. Early 2nd millennium B.C. Musée du Louvre. Image © Théo Truschel.

The text also takes on the dimension of a political testament intended for his successors, proposing a model of equity and social order. Finally, as is often the case in this type of document, it contains threats and imprecations against those who would destroy the monument.

Before the biblical laws, Hammurabi's code was the most important legal compendium of the Ancient Near East. Its size and the quality of its writing and language make it an exceptional artefact, as well as an incomparable source for our knowledge of the society, economic organization and religion of the period.

The epilogue

The epilogue