Bible, History, Archaeology

History,

Archaeology

Home > New Testament >

The four Gospels

The word Gospel comes from the Latin evangelium, itself borrowed from the ancient Greek εὐαγγέλιον/euaggelion).

The word «gospel» refers to the proclamation of «good news», such as the birth of a royal heir (Luc 2,10-11).

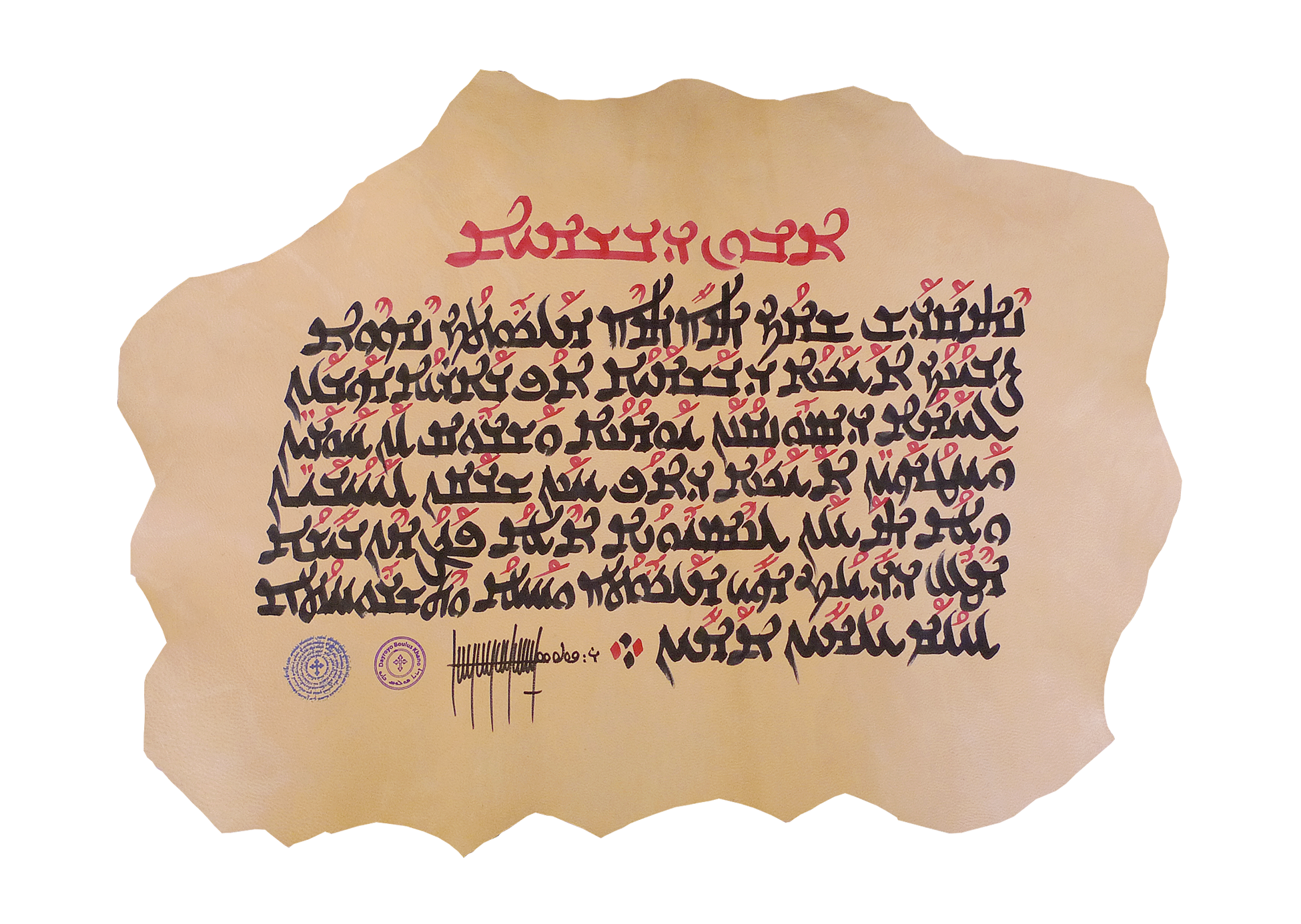

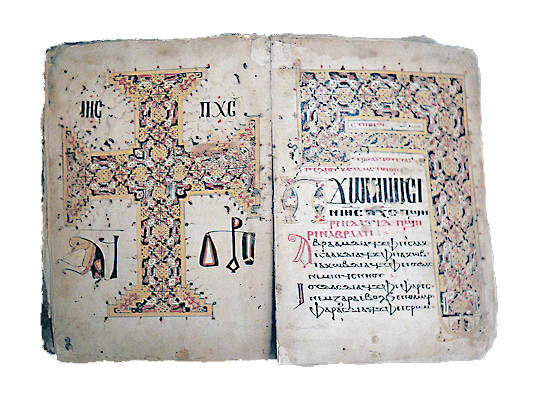

The title page and second page of the Gospel from Matthieu in Coptic and Arabic.

The manuscript dates from 1272 CE.

Coptic Museum, Cairo. © Théo Truschel.

In the Old Testament, besorah is translated into Greek as evangélion (gospel) in the Septuagint, the first Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible. It designates the reward for the announcement of a victory (2 Samuel 4, 10), the announcement of «good news» such as victory in a war (2 Kings 7, 9), the birth of a son (Jérémie 20, 15) or saving a friend's life (1 Kings 1, 42). Many happy events are associated with this term, which does not necessarily imply anything religious.

Introduction

Numerous gospels circulated during the first centuries of Christianity. We have no original text of any of them.

Image opposite: reconstruction of a scene depicting a disciple writing a page of a Gospel © DR.

Four Gospels are recognized as canonical by the Christian Churches: the Gospels according to Saint Matthieu, Marc, Luc and Jean. They form the most important part of the New Testament or New Covenant.

Other gospels, not recognized, are said to be apocrypha (from Greek ἀπόκρυφος/apókryphos, «hidden») a written «whose authenticity has not been established»(Littré). Catholic churches call them pseudepigraph «text falsely attributed to an author who did not write it».

At the sight of the crowds, Jesus goes up the mountain. He sits down and his disciples approach him. And, speaking, he teaches them:

Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth.

Blessed are those who weep, for they will be comforted.

Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness: they will be satisfied.

Blessed are the merciful, for they shall obtain mercy.

Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.

Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God.

Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness' sake: theirs is the kingdom of heaven...

(Matthew 5:1-10). Doron Nissim.

The Synoptic Gospels

The first three Gospels are known as the «synoptics», Matthieu, Marc and Luc which can be arranged in parallel columns and read «with a single glance» (Greek, synopsis). When we study the Gospels, it becomes clear that the one from Jean is different from the other three.

The first three Gospels share many similarities, suggesting that their authors drew on common sources. This observation had already been made by the ancients - especially by the bishop-historian Eusebius of Caesarea (± 340), author of the first major history of the Church (Ecclesiastical history) - but it wasn't until the end of the 18th century that the first synopsis was printed, enabling comparisons to be made between the texts of the four Gospels.

None of the evangelists claims to present a complete biography of Jesus of Nazareth. The Gospels are both practical and didactic in their reporting of Jesus« words and deeds. They are »committed" texts. On the other hand, while sharing a common vision, each of the three synoptic Gospels has its own characteristics, which determine the purpose of their authors and the readers to whom they are addressed.

- Matthieu, writing for the Jews, emphasizes the kingship of Jesus, the Son of David, the Mashiach (Messiah in Greek); he draws on numerous quotations from the Old Testament or First Covenant and sets out to present the teaching of Jesus of Nazareth on the true kingdom of heaven, in opposition to the nationalist conceptions accepted within Judaism at the time.

- Marc, writing for the Gentiles, no doubt for the Romans, insists on Christ's power, manifested in his miracles.

- Luc, who accompanied Paul for many years, shows the Lord in the guise of a gracious Savior, caring with predilection for those left behind, the outcasts and the destitute.

- Jean, for its part, aims above all to present Jesus as the divine Word incarnate, revealing the Father to those who consent to accept him.

It has often been asked from what sources the evangelists drew their information. Matthew and John, being apostles, witnessed the events they report, or were directly informed by eyewitnesses. Mark accompanied Paul and Peter; an ancient tradition states that Mark summarized Peter's preaching on Jesus in his Gospel. Luke himself certifies that he was informed by eyewitnesses, and that he knew everything exactly, from the very beginning (Luc 1, 1-4).

So the Gospels give us the testimony of the apostles.

The Gospel of Matthew

Its history

The Gospel according to Matthieu (Τὸ κατὰ Ματθαῖον εὐαγγέλιον) is the first book of the New Testament and the first of the four Gospels. Matthew, also named Levi, was the son of Alphaeus. Although a Hebrew, he worked as a publican in Capernaum, so despised and hated by the Jews that the latter often associated them with «people of ill repute».

It's safe to assume that he's wealthy, as are almost all those in this profession (witness the size of the meal he offers Jesus and the number of guests).

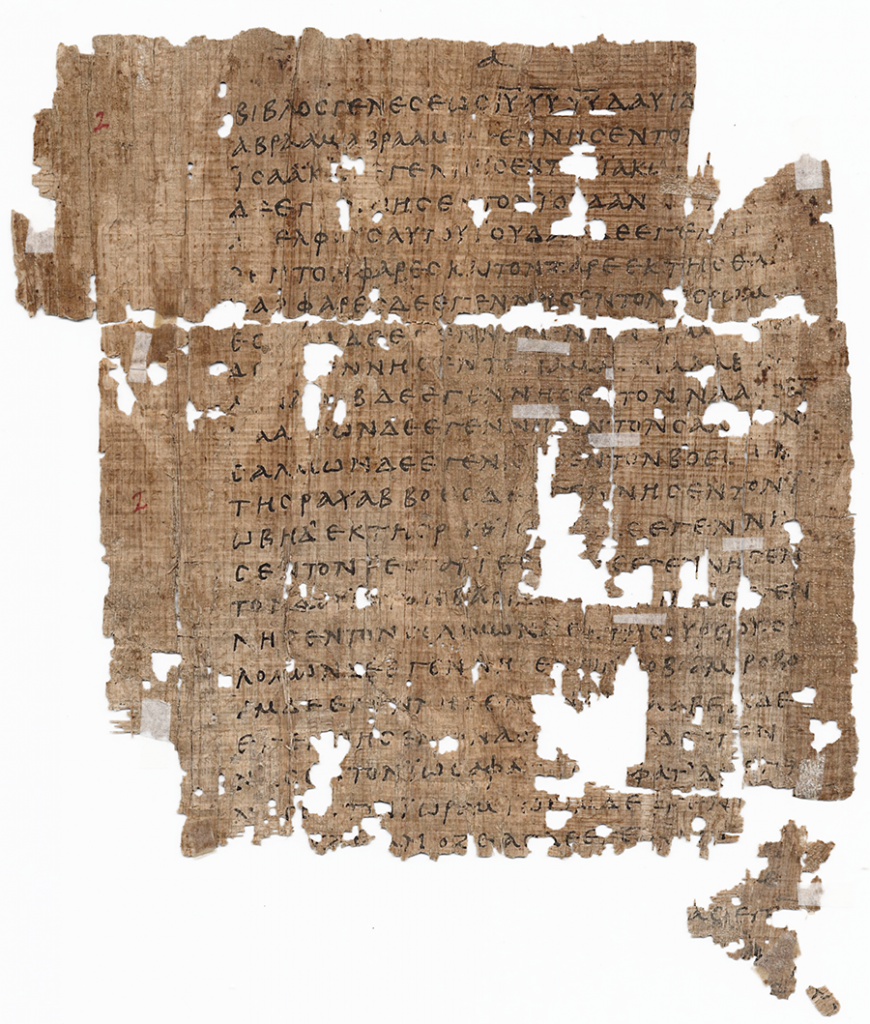

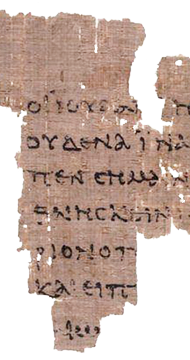

Image opposite: a fragment of a page from the Gospel of Matthew, in Alexandrian Greek, dating from the 3rd century. Chapter 1,1-9, 12 and 14-20. It was discovered by Bernard Pyne Grenfell and Arthur Surridge Hunt at Oxyrhynque in Egypt in 1896-1897. It is currently preserved at the University of Pennsylvania. DR.

His Gospel

Matthew is generally regarded as the author of the Gospel that bears his name, but there is disagreement as to whether the book was first written in Hebrew, Syro-Chaldean (Aramaic) or Greek. The problem is complex to resolve.

Since this Gospel was obviously written for the Jews, it is logical to assume that it was first written in Hebrew or Aramaic, in the language spoken by those to whom it is addressed; but since, on the other hand, a single Hebrew manuscript has never been found, and the Greek text seems to bear all the hallmarks of an original work and not of a translation, the strength of the first presumption is considerably weakened.

Matthew, a tax collector, must have known Greek, and the latest studies seem to militate in favor of a primitive Greek text, or at least one written in Greek by Matthew. With Olshausen (Hermann Olshausen, History of the Gospels, p. 19.), accept the testimony of certain Fathers of the Church, who are in favor of an Aramaic text, and admit that Matthew himself translated his Gospel into Greek, in order to make it accessible to a greater number of readers. As the Greek language is more widespread, manuscripts in this language are more numerous, more widely used, and end up entirely absorbing the Hebrew copies, which can only be of use to Christians of Jewish origin, often in the minority in most Churches.

As for the place and time of writing, we can only conjecture with varying degrees of certainty. Traditional accounts of this apostle's life and activity are vague and contradictory: some say he died in Palestine, others in Ethiopia, others in Syria or Persia; he died of natural causes according to Nicephorus, or of martyrdom according to Isidore, Ambrose and others. Most probably, he wrote the Gospel in Judea, perhaps in Jerusalem, before the destruction of this great city, whose ruin he announces as imminent (Matthieu 24, 1 et seq.) It was written between 60 and 70.

The Gospel of Mark

Its history

Mark, the author of the second Gospel, was probably the son of one of the New Testament Marys, a cousin of Barnabas and perhaps, like Barnabas, a Levite by birth and a companion of Paul and Peter. He is mentioned in the Acts of the Apostles under the names John Mark (Acts 12, 12-25), John (Acts 13, 5-13) and Mark (Acts 15, 39).

Image opposite: the title page and second page of the Gospel of Mark in Coptic and Arabic. The manuscript dates from 1272. Coptic Museum, Cairo. Theo Truschel.

Some time later, however, Mark returned to his career, but Paul did not want him as a traveling companion at first; he chose Silas, while Mark and Barnabas returned to Cyprus, where we have no information on the results of their mission there. Later, Mark returned to Paul, who counted him among his companions in Rome (Philemon 1, 1-24), recommends him to the Church of Colossae (Colossians 4, 10) and asks Timothy to bring him back (2 Timothée 4, 11).

It seems that, during the time between Paul's two captivities, Mark was Peter's companion, with whom he was united by filial affection, and was with him when he wrote his First Epistle (1 Pierre 5, 13).

If, as can be deduced from 2 Timothée 4, 11, Mark was present during Paul's last days, and we can assume that, after Paul's death, he returned to Asia to join the apostle Peter. One tradition adds that Peter sent him to preach the Gospel in Egypt, where he founded a very important Church in Alexandria and as far as Cyrenaica. He is said to have been murdered in the middle of a pagan festival in Alexandria. Some say his body was burned, others that it was transported to Venice, where a magnificent basilica bearing his name was built as a mausoleum.

His Gospel

Image opposite: an introduction to the Gospel of Mark in Coptic and Arabic. 16th-century manuscript, Coptic Museum, Cairo. Theo Truschel.

Even supposing that Mark wrote in Rome for the Christians there, there is no proof that he did so in Latin, Greek being more universal and better mastered than Latin.

It is thought that Mark has Matthew's work in front of him, and that he wants to make it accessible to Gentiles, by cutting out everything that relates exclusively to the morals and hopes of the Jews. He has a more universal aim than the first of the Gospels, but in this respect his coloring is less pronounced than that of Luke, which follows him. He is first and foremost an evangelical historian; he recounts what the Savior did, and we might give as an epigraph to his book these words by Peter, his companion and spiritual father: «he went from place to place, doing good» (Acts 10, 38). Everything is quick and brief in his account, and the words «at once» and «at once» occur forty times in his Gospel; he tells the facts, omitting or abbreviating words and speeches. Despite being the shortest of the four Gospels, his account is often livelier and richer in detail.

Nothing can be said about the time of writing: according to Irenaeus, Mark wrote only after the death of the apostles Paul and Peter; but as the date of Peter's death is not known, this vague indication is not sufficient. Some exegetes put the date of Mark's Gospel around 68.

The Gospel of Luke

Its history

Luke, the author of the Gospel that bears his name and of the Acts of the Apostles is, according to Eusebius of Caesarea, Jerome and Nicephorus, a native of Antioch in Syria and a physician by profession.

Jewish, but Nice by birth (Colossians 4, 14 ; 2 Timothée 4, 11), he would have had an intellectual training that stands out for the purity of his style. We don't know how he came to know the Gospel, but we can assume that it was through the ministry of the apostle Paul, whose friend and companion he was.

For us, the story only begins with the voyage of Troas (Acts 16, 10), probably his first encounter with the apostle, as he begins to speak of him in the first person. He followed Paul to Philippi, to the house of Lydia, a purple merchant, and appears to have stayed there for some time, despite the persecution suffered by Paul and Silas; we find him there again several years later (Acts 20, 6). He then resumed his travels with the apostle, accompanying him to Troas, Assos, Mytilene, Rhodes, Tyre, Caesarea and Jerusalem (Acts 21, 15), where he probably remained until Paul's departure for Rome (Acts 27, 1).

Tradition provides only uncertain data on the rest of his life. According to Jerome, he died at the age of eighty-four; according to Epiphanius, he preached the Gospel in Dalmatia and Gaul, and according to Nicephorus, he suffered martyrdom in Greece. The Fathers of the Church already know of his tombs in Thebes, Boeotia, Bithynia, Ephesus, Elea, the Peloponnese and elsewhere.

His Gospel

It was probably in Rome, before the writing of the Acts of the Apostles and consequently in the first two years of his stay, that Luke would have written the Gospel to which tradition unanimously gives his name. This is deduced from the fact that both works are addressed to the same person, a certain Theophilus, who is probably Roman and whose acquaintance Luke undoubtedly made in Rome. The author gives a great deal of detail on the geography of Palestine, which he seems to assume is little known to his reader, while he passes over, without explanation or indication of any kind, everything concerning the topography of Italy, as known by the «Theophilus".«Right Honourable Theophile». The title «most honorable» or «excellent» that Luke attributes to Theophilus is used to designate members of the equestrian order in Rome.

Having reached Paul's stay in Rome, the narrator reports almost nothing of Paul's trials, action and life, which would be of interest to Jerusalem readers if Luke were writing for them, but is superfluous for Roman readers who are, as much as Luke, privy to Paul's affairs.

The purpose of his Gospel

As for his Gospel, despite its obvious links with those of Matthew and Mark, which were probably already composed in his time, Luke's use of it can be distinguished; it differs from both in its general and universal orientation. The Gospel of Marc is, in this respect, without pronounced character. The Gospel of Matthieu bears the Jewish stamp in every passage, while the one from Luc, the Christ of humanity, the Covenant of God with all the earth. This difference can already be seen in their genealogies of Jesus of Nazareth: Matthew traces Jesus' ancestors back to Abraham, the Father of the Hebrews, while Luke counts them as far back as Adam, the Father of mankind. Matthew insists above all on the Jewish character of the Messiah, Luke on his human character. His Messiah is more of a Savior than a King; he willingly recounts his conversations rather than his speeches, and lets his interlocutors express themselves, reporting their questions and remarks. He focuses on details, recounting the births of John the Baptist and Christ, Jesus' first interview as a child in the Temple, the resurrection of the young man from Nain, the mission of the seventy disciples, the parable of the Samaritan, the story of Martha and Mary, the healing of the ten lepers, Jesus' visit to Zacchaeus, the conversion of the robber on the cross, the meeting with the two disciples on the road to Emmaus. The doctor's observation shines through in his account of certain miracles. He highlights Jesus' mercy for the sick, the afflicted and the broken-hearted, and often speaks of the effectiveness of prayer.

Visit Acts of the Apostles are the immediate and natural continuation of the Gospel of Luc. Luc undoubtedly wrote them shortly after his first work, and joins them together in the short foreword at the head of the second book...

The Gospel of John

Its history

The author of the fourth Gospel and three Epistles, the apostle John, originally a fisherman like his brother James, was the son of Salome and Zebedee (Matthieu 27, 56 ; Marc 15, 40). His parents seem to have been among those who awaited Israel's consolation; so we see Zebedee letting his son go when Jesus calls him, and consenting to the sacrifices Salome offers for Jesus.

Zebedee's family is from Bethsaida, which can be deduced from their fishing association with the families of Peter, Andrew and Philip, who seem to belong to the same village (Matthieu 4, 18-21 ; Jean 1, 44 ; 21, 3-7).

Image opposite: the oldest fragment of a Gospel of John (P52) discovered at the famous site of Oxyrhynchus, west of the main branch of the Nile in Egypt, dating from around 125 A.D. © The Exploration Society. The Imaging Papyri Project, University of Oxford.

To access the scientific study of the oldest fragment of the Gospel of John →

If John seems uneducated (Acts 4, 13), there can be no doubt that he was brought up in a religious environment and in expectation of the Messiah; he hears the preaching of John the Baptist the forerunner and is baptized by him in the waters of the Jordan. Then, when he met Jesus, he joined him. From then on, he benefited not only from his teachings, but also from a very special friendship. Along with Peter and his brother James, he was privileged to witness the healing of Peter's mother-in-law (Marc 1, 29), the resurrection of the daughter of Jairus (Marc 5, 37) and the transfiguration on Mount Tabor (? Marc 9, 2). In the dramatic moments of the crucifixion (Marc 14, 33), Jesus entrusts his mother Mary to him (Jean 19, 26).

The purpose of his Gospel

This is not a biography of Jesus of Nazareth as such. It seems to presuppose knowledge of the other three Gospels. Thus, it omits several important facts reported in the latter, such as the birth of John the Baptist, the birth and baptism of Jesus, the temptation in the desert, the calling of several of the apostles, the name Jesus gave them, the sending out of the seventy disciples, a large number of miracles and parables, the Sermon on the Mount, the Transfiguration, the institution of the Last Supper, the anguish of Gethsemane, the Ascension. He simply recalls what seems to be known. Most of the events he reports took place in or near Jerusalem, and he is more precise than the other three evangelists in naming place, time, people and circumstances. The miracles he reports are mainly those related to Jesus' teachings.

John's aim in writing his Gospel is that «you should believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God». John frequently uses the words «believe» and «life», the titles «Son» and «Son of God». «True», «truth», «love», «testimony» and «world» (Greek kosmos) are also terms peculiar to the apostle's writings. He is the only one to mention Christ's proclamations: «I am» (Jean 6, 35), as well as the expression «in truth, in truth» which precedes 25 statements, to underline their importance (Jean 1, 51, etc.).

Above: a manuscript of the Our Father prayer (in Latin) Pater Noster ; Greek original Πάτερ ἡμῶν, Matthew 6:9-13, etc.) in Syriac Aramaic. Vellum. St. Mark's Syro Orthodox Monastery, Jerusalem, Israel. Marc and Theo Truschel private collection.

Jesus' mother tongue was probably Aramaic, a language that was already a thousand years old at the time and had evolved considerably with the times and regions. The dialect spoken by Jesus is called Judeo-Aramaic; it differs from other Aramaic dialects of the time, such as Nabataean or Palmyrenian.

Syriac is also an Aramaic dialect, but it differs considerably from Judeo-Aramaic. Jesus didn't speak Syriac, and it's doubtful that he would have been able to understand it easily, as there are many differences: noun endings, conjugations, vocabulary and so on.

Syriac has survived as the liturgical language of some Eastern Churches, which is why the Lord's Prayer is often found in Syriac, in the mistaken belief that it is the ‘original version“ of this famous prayer. Similarly, the classic Syriac Bible (known as the ”Peshitta“) is often presented as the original version of the Gospels. Again, this is not the case; nor is the Peshitta the first Syriac version of the Bible. There are also versions in Christo-Palestinian Aramaic, a dialect closer to that of Jesus than Syriac, but later in date.

Find out more

NANOT Alexandre, The 4 gospels - NTB

Bibliorama collection. Published February 2025.

Entirely unpublished translation

This new translation of the 4 Gospels - NTB, based on the Greek texts, is first and foremost a translation proposal.

The basis for our work remains the Novum Testamentum Graece Nestle-Aland (28th edition), while taking into account the different variants present in other manuscript families. This is why the reader will find certain words or passages in square brackets that are found in the Codex Alexandrinus, the Vulgate, the Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis and a few lessons from the majority text.