Bible, History, Archaeology

History,

Archaeology

Home >

The Coptic Church

Contents:

Introduction - The origin and meaning of the Coptic word - The Roman period and the beginnings of Egyptian Christianity - The Byzantine period - From the Byzantine to the Islamic era - The Mamelukes and the Ottoman occupation - Copts, from the 19th century to the present day - Mass in a Coptic church in Old Cairo - An original civilization

The origin and meaning of the Coptic word

The origin and meaning of the Coptic word

Hikuptâh («the house of Ptah's spirit») is the religious name of Memphis, the ancient capital of Pharaonic Egypt. The Greeks derived the name aiguptios (Egyptian).

In 641, the Arab conquerors took over the name aiguptios which soon became abbreviated to Qibt (قِبط), i.e. Coptic.

The name Coptic was first used to designate the Egyptian population as a whole, then, as people converted to Islam, exclusively the members of the Christian Church of Egypt.

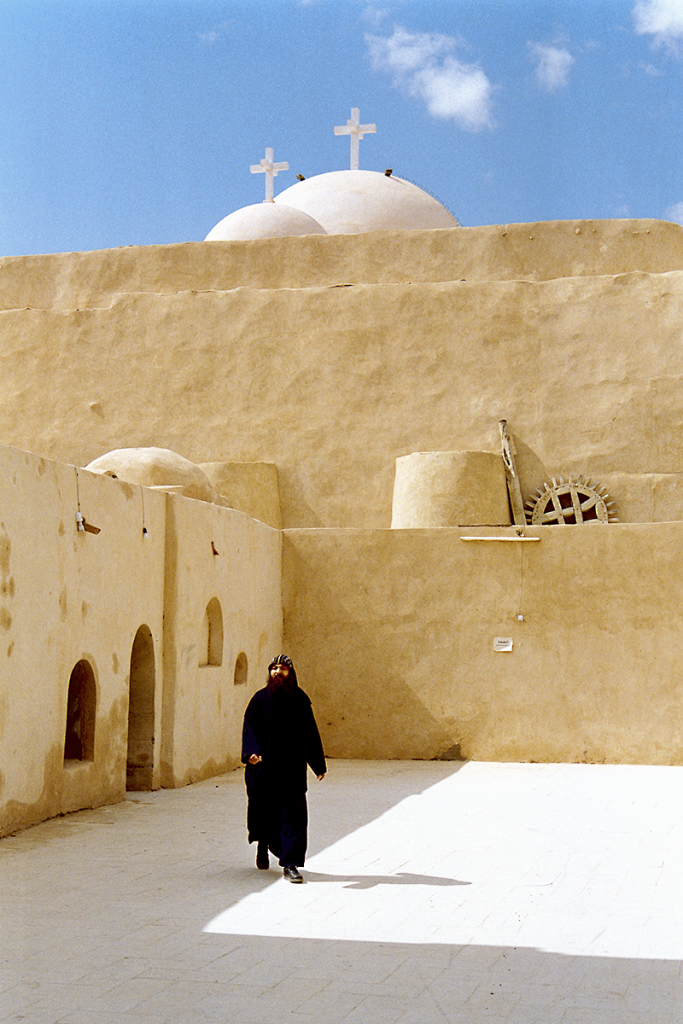

Opposite image: a monk wearing the «Saint Anthony» hood, embroidered with Coptic crosses. © Théo Truschel.

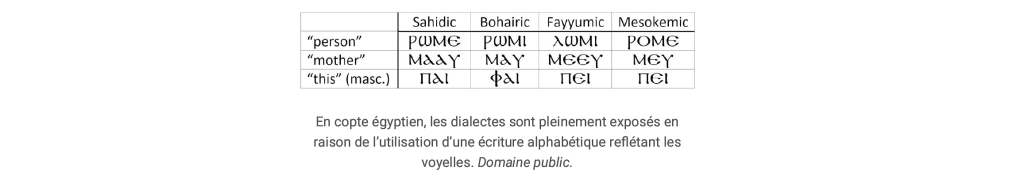

The Coptic language is the latest stage in the evolution of ancient Egyptian. Several regional Coptic dialects existed: Bohairic, Sahidic, Fayumic, Oxyrhynchite, Akhmimic and Lycopolitan.

Only Bohairic, which has become a dead language, is still used, but only in the liturgy. It is probably from this linguistic heritage that a contemporary Coptic identity has emerged.

The Roman period and the beginnings of Egyptian Christianity

The roots of Egyptian Christianity

Christianity took root very early in Egypt, between 42 and 48 CE. Ancient Coptic tradition attributes the very beginnings of Egyptian Christianity to the «Coming of the Holy Family» who fled from King Herod the Great in Egypt (Matthieu 2,13-15), then to the preaching of the evangelist Mark in Alexandria.

It was during this period that the School of Alexandria was established: the famous Didascalea, which trained a large number of theologians and Church Fathers; illustrious figures such as Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Jerome, etc., emerged from this School and laid the foundations of Christian teaching.

From the outset, Christianity had a special status. Like the Jews, Christians did not take part in the official worship of the state, offering incense to the gods and the emperor, and were therefore on the bangs of the law.

The first persecutions

In 202, Septimius Severus promulgated an edict forbidding both Jewish and Christian proselytizing; as a result of this edict, the Alexandrian School was disorganized and some were martyred.

The first systematic persecution was unleashed by the emperor Decius (circa 250), who demanded that Christians make offerings to the imperial gods and receive a certificate attesting to this. Several of these certificates have survived. When the persecutions ceased, the Christians who had received these certificates were reprimanded.

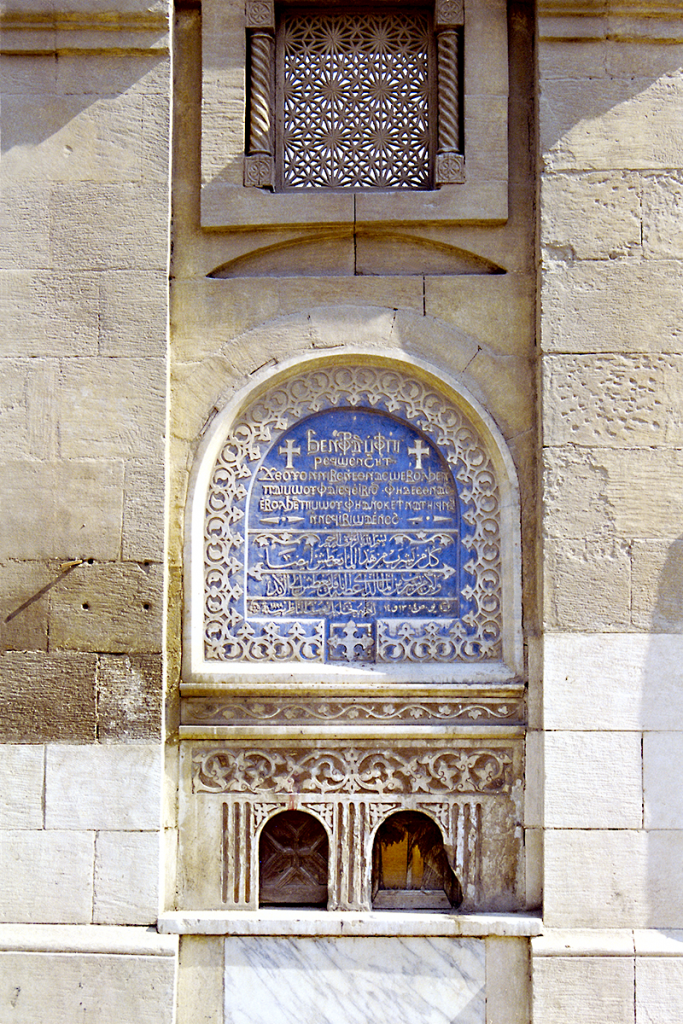

Image opposite: Coptic and Arabic inscriptions on the façade of a church in Old Cairo. © Théo Truschel.

«Jesus answered and said to him, »Whoever drinks of this water will thirst again; but whoever drinks of the water that I shall give him will never thirst, and the water that I shall give him will become in him a spring of water welling up into eternal life". Gospel of John 4:13-14.

Around 304 AD, the emperor Diocletian unleashed a particularly bloody persecution in Egypt. It was so terrible that Egyptian Christians declared the year of Diocletian's accession (284) the first year of the Coptic period (Year of the Martyrs). There was a split in the Egyptian Church between those who had remained firm in the faith and those who had sacrificed to idols (the lapsi), over their reintegration into the Church.

Image opposite: silver antoninian (two-denarius value), Rome, circa 249-251.

Obverse and reverse.

In effigy of Emperor Decius, who unleashed the first systematic anti-Christian persecution around 250 AD. @ Frédéric Weber Collection.

Persecution ended in 311, and Constantine's ’Edict of Milan« in 313 granted Christianity freedom of worship. Christianity became the state religion in Egypt in 391.

Despite persecution, the 3rd and 4th centuries were favorable to the expansion of Christianity: initially limited to the big cities, it gradually spread to the countryside (communities existed in Fayoum, for example) and Coptic became the liturgical language alongside Greek.

The Byzantine period

The various councils and the schism

A few years after the «Edict of Milan», a certain Arius, an Alexandrian priest, professed a new doctrine, claiming that Christ was simply the most perfect of God's creatures, and that his nature resembled God's without being identical. Emperor Constantine convened a council at Nicaea in 325 to deliberate and resolve this point of doctrine, which was roundly condemned.

On the other hand, paganism was not dead for all that. In 391, Patriarch Theophilus incited a mob to destroy the Serapeum, Alexandria's great pagan temple; in 415, extremists murdered the philosopher Hypatia, a symbol of the study and science that some fanatics identified with paganism.

In 457, fearing that Egypt was slipping out of his control, the Emperor of Constantinople appointed Proterius, who favored him, to take over the leadership of the Egyptian Church. The Melkite representative (a term that comes from malka, Aramaic for «emperor» or «king) was lynched by the Egyptians, who refused to accept a foreigner as head of their Church. With imperial authority challenged and the country destabilized, imperial troops were no longer able to use Egypt as a strategic base. To re-establish its authority, Constantinople first used persuasion and then repression, without success.

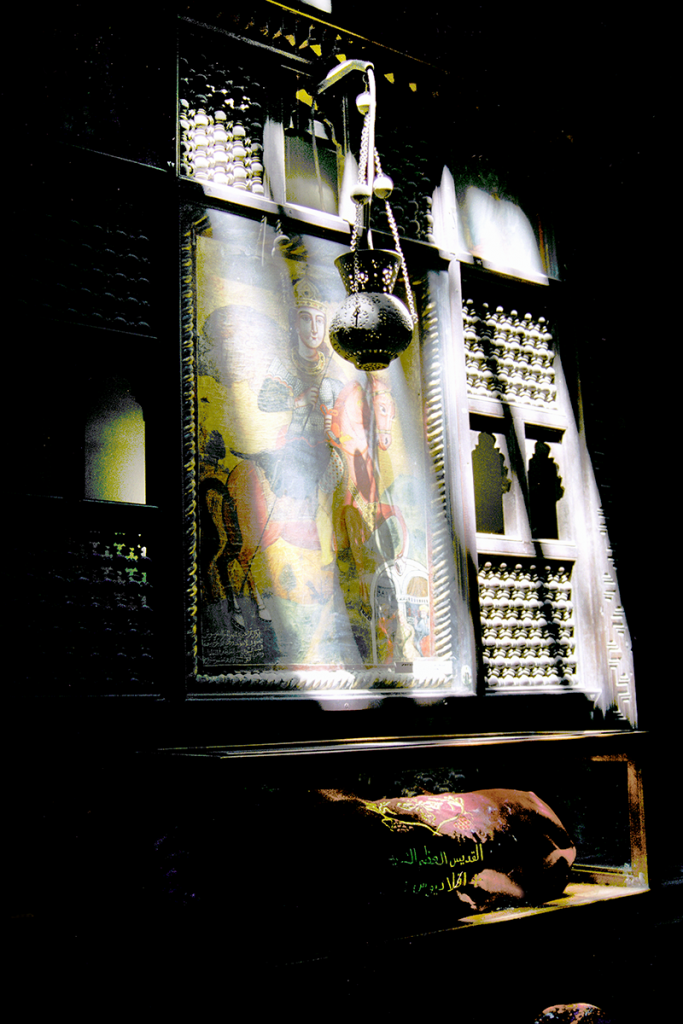

Image opposite: one of the magnificent frescoes in a Coptic church in Old Cairo depicting the 4th-century Christian martyr Saint George. Most ancient Coptic churches have relics that are either encased in silk brocade or preserved under glass, as shown here. © Théo Truschel.

In the 6th century, the emperor Justinian succeeded in restoring a certain order by reorganizing Egypt's defenses.

The Eastern Emperor faced numerous threats, particularly from the Sassanid Persians, who succeeded in breaking through the defenses, entering Alexandria victorious and remaining masters of Egypt for ten years. The Persian Sassanid occupation caused great difficulties in Egypt, and 600 monastic establishments were destroyed by the Persian army. However, during this dark period, many Church leaders showed great courage. With the Persians expelled in 629, Constantinople regained power in Egypt, but relinquished it when the Arabs invaded in 641.

From Byzantine to Islamic times

The arrival of Islam

With the invasion of the Arabs came a new religion, Islam. At first, non-Muslims were not forced to adopt it. According to Muslim tradition, the Prophet had a Coptic wife whom he had particularly loved, and gave instructions that Egyptians should be respected after his death.

The Arab conqueror of Egypt, Amr Ibn el-As, invited Patriarch Benjamin (632-662) to return from exile in Alexandria. This was viewed positively by the Christians, who were able to practice Nestorianism freely, happy to be rid of Byzantine tutelage.

At the end of the 7th century, tensions arose between the two communities on the grounds that the current Coptic patriarch did not show sufficient respect to the governor of Alexandria.

Image opposite: today, the Coptic Church gathers several million faithful who come to pray fervently in churches founded in the 4th century. Here, during a mass in a church in Old Cairo. Christophe Jeanjean.

During the 9th century, relations deteriorated again, and Christians were obliged to wear a yellow turban and a special belt to be recognized. Crosses were removed from churches, and building activity declined.

The Fatimids

In 969, the arrival of the Shi'ite Fatimids (descendants of the Prophet's daughter Fatima) led to the construction of a new capital, Cairo, where the Coptic patriarch took up residence. Yet the 1st Fatimid century was marked by tragedy. The first Caliph, al Hâkim (996-1021), decreed heavy-handed discriminatory measures such as the prohibition of public celebrations, the destruction of numerous churches, forced conversions to Islam, and so on. Persecution ceased with the death of the Caliph, and a happier era dawned for the Copts. The Copts regained their leading positions in the administration, and the Church underwent a revival. Nevertheless, as the Christian population became a minority in an Arab-Islamic country, the Coptic language lost ground and was increasingly confined to the liturgy. Coptic authors wrote in Arabic, and from the end of the 12th century, the liturgy itself began to be celebrated in Arabic.

The Ayyubids

Salah El-Din had a fortress built at the highest point of the city, the Citadel, which was used as the seat of government for the next 700 years.

Image opposite: Coptic bishop, priests and laity in discussion after a service. Theo Truschel.

The Mamelukes and the Ottoman occupation

The Mamelukes

The collapse of the Ayyubid dynasty had its origins in the large number of Turkish slaves enlisted in the army. Over time, they had acquired sufficient importance to seize power; they were called Mamelukes, from the Arabic word for slaves. The era ushered in by the Mamelukes in 1251 was a period of great violence, but also of great artistic production. Their main contribution was to preserve Egypt from the Mongol hordes who had already devastated Persia and Iraq.

Two groups of Mamelukes ruled the country in turn: first the Babris Mamelukes (a word meaning river, as their headquarters were located on Rhoda Island, opposite Old Cairo) until the mid-13th century, and then the Burgi Mamelukes (a word meaning tower, as they were stationed at the Citadel) until the Ottoman conquest.

Image opposite: a bas-relief in a Coptic church in Egypt © WitthayaP.

From the 13th to the 14th century, the Church underwent a remarkable cultural revival in the Arabic language in a number of fields: the arts, philosophy, theology and literature, especially of religious inspiration.

The Ottoman occupation

The Ottoman Turks, who had seized the Byzantine Empire, did not want to conquer Egypt by force of arms. On two occasions, they offered the Mamluks semi-independent status within their Empire. The Mamluks refused, preferring to fight until their defeat at Guizèh in 1517.

Under the Ottoman occupation, the Mamluks regained a certain importance, to the point of once again becoming the masters of Egypt around 1767. Various pressures, and above all a heavy tax burden on Christians, began the decline of the Coptic community.

Copts, from the 19th century to the present day

During his Egyptian campaign (1798-1801), General Bonaparte, anxious to maintain good relations with the Arab-Muslim elite, lost interest in the Copts. On the other hand, Viceroy Mehemet Ali (1805-1849), who succeeded in expelling the Mamluks in 1811 and gaining independence from the Ottoman Empire, called on the services and skills of the Copts to manage the country. He aimed for a rapprochement with the West and began to bring Egypt into the modern age.

In 1855, Viceroy Mohamed Saïd (1854-1863) introduced military service for Copts, a step towards full citizenship. On his accession to the throne, Khedive Tewfiq (1879-1892) finally decreed the equality of Christians and Muslims. As never before, the Copts played a leading role in the life of the Egyptian nation. Egypt even had a Coptic Prime Minister, Boutros Ghali Pasha, who was sadly assassinated by a Muslim extremist in 1910.

From the 1930s onwards, the rise of Islamic sentiment and exacerbated nationalism (the Muslim Brotherhood) compromised the remarkable positive climate that had been established in Egypt, but the Copts nonetheless experienced a revival of identity and dynamism.

Discredited by corruption and the 1948 defeat by Israel, King Farouk was overthrown in 1952, leaving the country in the hands of Colonel Gamal ‘Abd el-Nasser, who embarked on a process of socialization that was to be particularly hard on Christians. Many Coptic families were dispossessed of their assets in banking, industry and commerce. All political parties in which Copts played an important role were suppressed. Despite this, the «dark years» saw a revival of the Church, largely due to the energy of Patriarch Cyril VI (1959-1971), who was particularly revered by the Copts. He restored a number of monasteries and led the Church back to the spirituality of the «Desert Fathers».

Image opposite: one of the entrance doors (now condemned) to the porch of the Al Muallaqa church, which dates from the 13th-14th centuries. It is the oldest Coptic place of worship in Old Cairo, dating back to the 4th century © Théo Truschel.

The Sadat years

With the accession to power of President Anwar Sadat (1970), the situation of the Copts improved. The Coptic Minister of State Boutros Boutros Ghali (UN Secretary General from 1992 to 1997) provided important support, but Sadat's policies also fed the fundamentalism of Muslim fundamentalists, who had him assassinated in October 1981. Several bloody clashes between Christians and Muslims took place in this fragile political context: Pope Shenouda III was officially deposed.

In 1981, President Hosni Mubarak, whose wife was a Christian, set about restoring the situation, and in an effort to appease the situation, Shenouda III was reinstated as head of the Church in 1985.

In February 2011, President Hosni Mubarak stepped down after 18 days of intensive protests, ending his 29-year reign over Egypt. The army seized legislative and executive powers. The following month, Egyptians approved by referendum a reform of the Constitution that provided for a rapid transition to elected civilian power. In November 2011, further violence erupted, killing several people and prompting the army to speed up the transfer of power.

In the 2011-2012 parliamentary elections, the Islamists won the majority of seats. On June 17, 2012, after a second round of voting, Mohamed Morsi won the presidential election to become the country's first president elected by universal suffrage in a free election, with 51.7 % of the vote against Ahmed Chafik, former prime minister under Mubarak.

Mohamed Morsi's presidency began on June 30, 2012 and, massively contested ended on July 3, 2013, after a military coup led by General Abdelfatah Khalil al-Sissi.

The period from 2011 to 2013, when the Muslim Brotherhood came to power, was a difficult time for the Copts.

Today, the Coptic Church brings together several million faithful who come to pray fervently in churches founded in the 4th century.

Here, during a mass in a church in Old Cairo. Sun_Shine

An original civilization

The birth of the Coptic alphabet

By the 3rd century, part of the Egyptian population had become Christian, but the spread of the Gospels among the people came up against difficulties in reading the traditional scripts (hieroglyphic and demotic). The Greek phonetic script was then adapted to Egyptian customs and completed: this is Coptic.

In ancient Egypt, people have always fled from the hardships of life (army, taxes, etc.) by taking refuge in the desert. This was also the case during the persecutions of Christians in the 3rd and 4th centuries. The first Christian hermit was Paul of Thebes, who lived in total solitude in a cave. Others followed, the most famous being Saint Anthony, who made this choice in line with the Gospel message (poverty) and not because of persecution. However, around 305, he abandoned total eremitism and agreed to live with a few disciples, for whom he drew up a rule of life. This marked the beginning of monasticism, traces of which can be found in the Egyptian desert, in Wadi n-Natroun and in the Delta.

Later, Pachôme founded another form of monasticism, a community life that balanced solitude with communion with other monks: this is Koïnos bios, life in common, which gives rise to the word cenobitism.

Saint Amoun, for his part, established a form of semi-anachoretism: cells (Kellia) isolated from one another in the middle of the desert, where a monk lived with a few disciples (between 5 and 10 hermits), but which made it possible to meet once a week for mass.

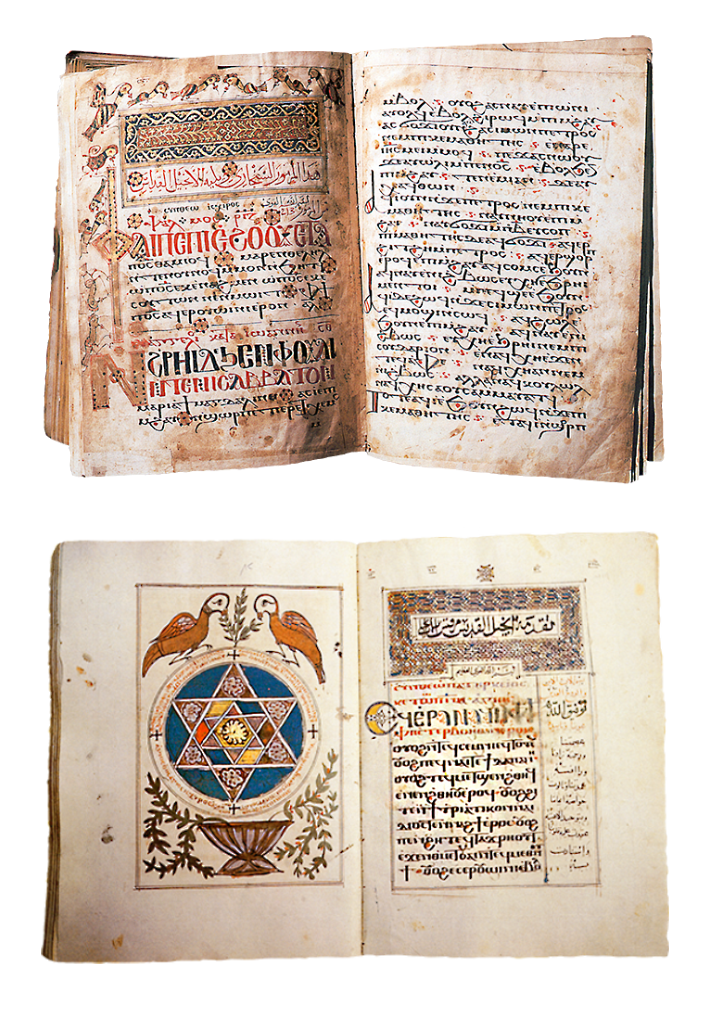

Image opposite: top image: 14th-century Coptic liturgical book containing verses 24 and 25 of Psalm 118 © Théo Truschel.

Bottom image: Coptic and Arabic manuscript from the early 16th century. Introduction to the Gospel of Mark © Théo Truschel.

The art

Coptic art is deeply influenced by Egyptian, Greek and Roman art. From the 5th century onwards, religious subjects proliferated (including numerous crosses), triumphing in the 6th century. Iconographic references go back to the pagan past and are inspired by it: typically Egyptian animal and plant decorations (e.g. crocodiles, ducks, hippopotamuses, etc.), geometric decorations, etc. They can be found on all media: mosaics, fabrics, paintings, etc.

In the 16th century, the Copts aroused a certain interest in the West, inspiring pilgrims and diplomats to make several trips to Egypt. In 1538, Guillaume Postel published the first Coptic alphabet. This was also the period of manuscript and lexicon discoveries, notably in the monasteries of Wadi n-Natroun. In 1675, an Egyptian Christian, Yousouf Abou Daqan, who had already taught in Europe, published a History of the Copts in Latin.

To date, the oldest copy of a small part of the New Testament has been unearthed in Egypt's Fayum region. It is a papyrus fragment containing a passage from the Gospel of John. It is dated to the first half of the 2nd century.

In the 18th century, knowledge of Coptic progressed with the publication of works such as Veyssière de Lacroze's dictionary (1775) and Scholtz and Woide's grammars (1778). It was above all this documentation that enabled J.-F. Champollion to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphic writing in 1822.

Image opposite: today, there are 13 monasteries inhabited by several hundred monks, as well as numerous renovated ancient monastic sites. Bishops are chosen from among these monks. Theo Truschel.

The Coptic Church today

The economic difficulties facing Egypt today are encouraging Islamist rhetoric. The Copts are often presented as a scapegoat, guilty of these various national difficulties. The Coptic Church, out of a concern for peace and national solidarity and to prove its loyalty to its country, plays down these difficulties.

Copts are far from being a negligible minority (6% in government censuses but 12 % for Copts) and are present in all areas of the Egyptian economy and culture.

The origin and meaning of the Coptic word

The origin and meaning of the Coptic word