Bible, History, Archaeology

History,

Archaeology

The Bible canon

Contents:

Introduction - Definition - Image of an ancient Torah scroll - The Old Testament canon - First form of the Old Testament - Second form of the Old Testament - The three-part arrangement - The Orthodox Christian canon of the Bible - Image of a sofer (scribe) - The New Testament canon - Each book was written separately - An image of an early theological library - From church to church - Non-canonical Christian books - Canon formation - The criteria of canonicity - The «deuterocanonical» and «apocryphal» books» - The Vulgate

Introduction

Have you ever noticed that Catholic and Orthodox Bibles contain more books (73 to 75 books) than Jewish and Protestant Bibles (66 books)? What's more, the classification is different in Judaism.

This observation applies only to the Old Testament (First Covenant).. As far as the New Testament (New Covenant) is concerned, the various Christian denominations are unanimous on the 27 books selected.

Definition

the biblical canon, from ancient Greek κανών, «kanôn» comes from «cane»: a straight reed, rod, or straight piece of wood to which something is attached that must remain upright.

the biblical canon, from ancient Greek κανών, «kanôn» comes from «cane»: a straight reed, rod, or straight piece of wood to which something is attached that must remain upright.

Metaphorically, the canon is any rule or standard, principle or law concerning judgments, life, actions.

«The word canon means a ruler used to measure, and by extension, that which is measured» (Pache).

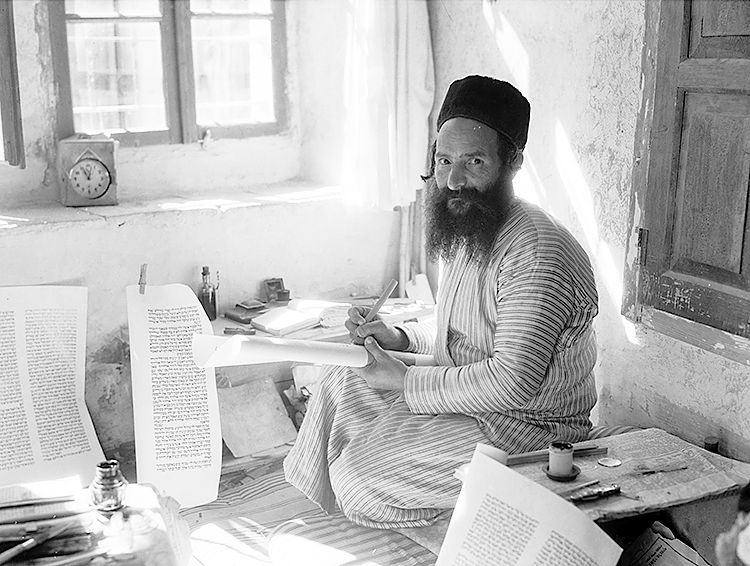

Image opposite: A Yemeni sofer (scribe) writing a Torah text. Early 20th century. © Library of Congress, U.S.A.

Athanasius of Alexandria (296/298 - 373) was the first Church Father to use the word «canon» in this sense. He asserted, for example, that The Pastor of Hermas, composed in Rome in the first half of the second century, does not belong to the canon. The «canonical» scriptures are those that are the standard, authentic and authoritative basis for Judaism (Old Testament) or Christianity.

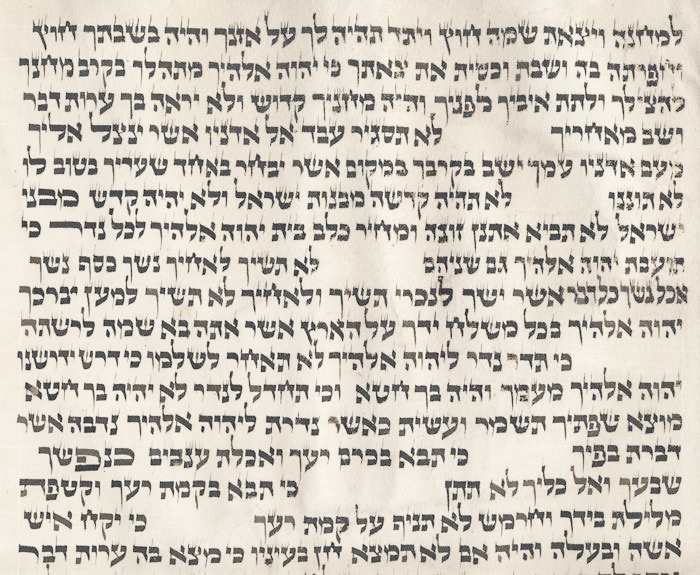

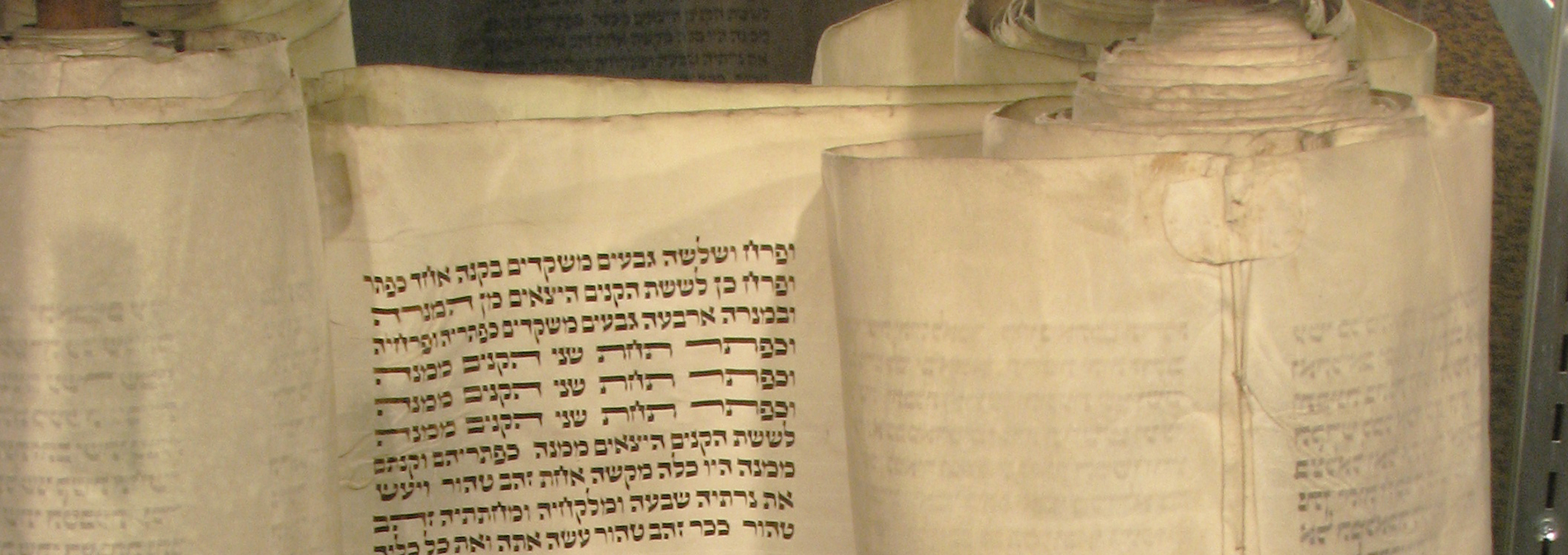

An ancient Torah scroll (detail) on parchment. DR.

The Old Testament canon

or First Alliance

This raises the question of the Old Testament «canon» or, to put it another way, the status of divine inspiration accorded to certain books.

Where do these variations between different editions of the Bible come from, and how can they be explained?

Is there any historical documentation on the closing of the canon?

The Old Testament is essentially

in two different forms:

The first form

The Hebrew Massoretic Text

However, Jewish historical sources, in this case the Mishna, In fact, they only talk about debates concerning two books, Ecclesiastes and the Song of Songs. However, further discussions on these two books are to be found later on, calling into question the hypothesis of an official (even definitive) decision at Jamnia. In fact, the inspired authority and character of the books of Scripture (* Tanakh) were recognized long before the decision of the Council of Jamnia. These books were self-evident among the people of Israel, because they had become aware that God was speaking to them through these books. The canon is therefore also the rule of faith and life for believers.

Image opposite: a fragment of a Torah scroll from Deuteronomy 23:14, (detail) 72 x 26 cm, dating from the 16th century. Entirely handwritten on vellum. Private collection Theo Truschel.

* Visit TaNakh is the acronym for the three parts of the Hebrew Bible: Torah (Law, teaching), Nevi'im Rishonim and Aharonim (the later and earlier Prophets) and Ketouvim (The Writings).

The second form

The Septuagint (LXX) written in Greek

According to a tradition (legend?) reported in the Letter from Aristée (2nd century B.C.), the translation of the Torah (Pentateuch) is said to have been produced by 72 (seventy-two) translators in Alexandria, around 270 BC, at the request of Ptolemy II Philadelphus for his Library of Alexandria.

Image opposite: Ancient Greek gold pentadrachm coin depicting Ptolemy II Philadelphus, circa 274 BC © cgb.

Orthodox« Judaism did not adopt the Septuagint (even though it was well received by the Greek-speaking Diaspora), remaining faithful to the Masoretic Text, and to Greek or Aramaic translations (Targum) closer to it according to their authorities.

Although these two forms of the Old Testament are quite similar, there are a number of differences. The Greek version differs from the Hebrew in the arrangement of its biblical books. The Hebrew text is organized as follows the Torah, then the Prophets and finally Writings. The Hellenistic canon reflected in the Septuagint, on the other hand, is organized into four parts, namely the Pentateuch (corresponding to the Torah, Pentateuch), Historical books, Poetic books and the Prophets. Most of the introductions to our study Bibles show these differences.

The three-part arrangement

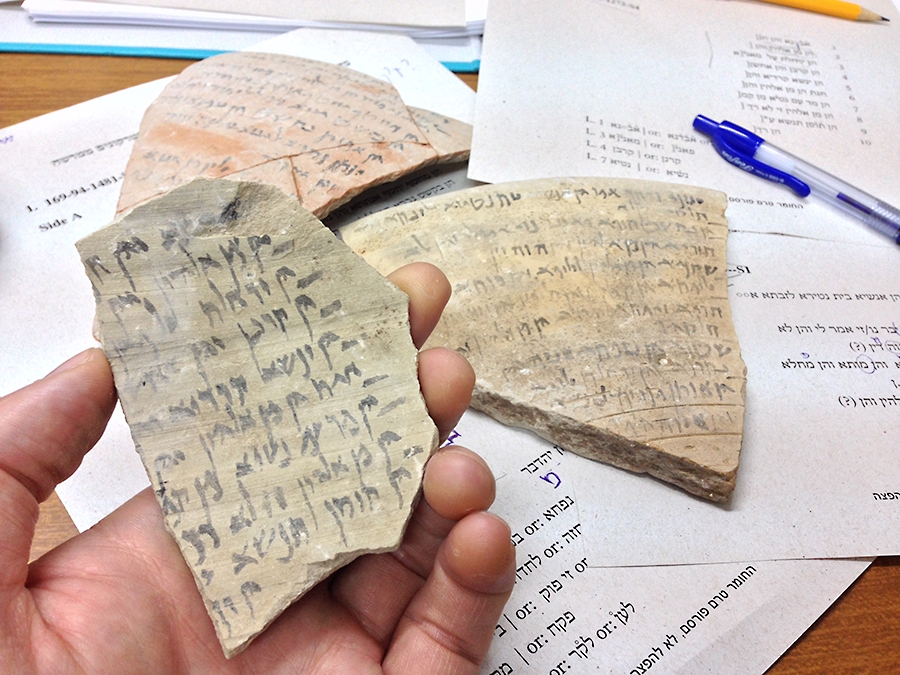

Image opposite: an epigraphist studying and translating ostraca (plural of ostracon) in ancient Hebrew. Michael Langlois.

Differences between the Hebrew and Greek texts koinè, The Septuagint includes certain books that the Masoretic Text omits. These include the books of Judith, Tobit, 1 and 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, Letter from Jeremiah and additions to the books of Esther and Daniel are the seven books retained in the Catholic tradition but which have come down to us in Greek; they were rejected by both Jews and Protestants.

The Orthodox Christian canon of the Old Testament

The Orthodox version of the Old Testament canon includes all the books found in the Septuagint, as well as those mentioned above, 3 and 4 Maccabees, 3 and 4 Ezra, Manasseh's prayer and the Psalm 151. All these books are Jewish writings, and some of them, like the 1 and 2 Maccabees, The new "intertestamentary" period between the end of the Old Testament (book of Malachie) and the New Testament (Gospel of Matthieu). Some of these works were also quoted by the Church Fathers, and fragments in Hebrew or Aramaic of Sirach, of Tobit or the Psalm 151 in the Dead Sea Scrolls.

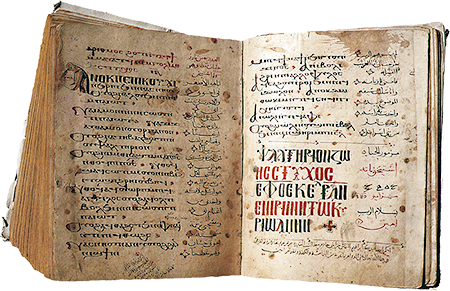

Image opposite: the last two pages of Psalm 151. Coptic Patriarchate Library, Egypt. Twelfth-century manuscript in Coptic and Arabic © Théo Truschel.

Image opposite: the last two pages of Psalm 151. Coptic Patriarchate Library, Egypt. Twelfth-century manuscript in Coptic and Arabic © Théo Truschel.

The apocryphal Psalm 151 is dedicated to David's fight against Goliath:

«[...] I went to confront the Philistine. He cursed me with his idols.

But I tore off his sword, beheaded him and washed the children of Israel clean.

No historical document really speaks of any official decision concerning the closure of the Old Testament canon. This makes historical research difficult.

The constitution of the Old Testament canon may therefore have been a gradual process, with groups of books added to one another over time, according to the authority and divine inspiration they were recognized to have.

While it is impossible to give a definitive date for the creation of the canon, three aspects can be highlighted to establish a probable range:

- First and foremost, The canon could not be closed until the last books of the Old Testament had been written, around the 6th/vth century BC.

- Next, important clues, such as a reference to the tripartite division of the Old Testament, can be found in the prologue to the book of the Sirach (130 B.C.), which suggests that the canon was already fairly well established by this time.

- Finally, Flavius Josephus, a Jewish historian of the 1st century AD, clearly testifies to a canon fixed in the 1st century BC, similar to that of the Masoretic Text.

A sofer (scribe) writing pages from the Tanakh © Dennis Diatel.

The New Testament canon

or New Alliance

The New Testament canon comprises 27 books. The four Gospels are among them, since they contain the accounts of the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. But we know that other «Gospels» were also written.

Why only these four Gospels and not the others?

This question also arises with regard to the Epistles, since it would seem that some of the apostles wrote letters other than those that form part of the New Testament.

We know more about the formation of the New Testament canon than we do about the Old Testament canon. In fact, we know of numerous works by Christian authors of the 2nd century (and even the end of the 1st century) that inform us of the problem the Church faced from the very beginning, and why it retained only the present 27 books of the New Testament.

Each book was written separately

Authors, recipients, dates and circumstances vary from book to book. Some historians now believe that most (if not all) of the books that make up the New Testament were written in the second half of the first century - Paul's first Epistles being written around the 50s/60s.

For other historians, it's not impossible that written collections of the sayings of Jesus of Nazareth already existed at this date (First, the Gospels of Marc, Matthieu, etc.), but there is no doubt that the memory of these words was transmitted orally by the apostles, and then by other disciples, from Pentecost onwards. We have an example of this in the Acts of the Apostles 20,35.

As early as the end of the first century, Christians recognized several New Testament books as inspired Scripture. In 2 Peter 3:15 and 16, Peter speaks of Paul's letters as part of the Scriptures. At the end of the first century (c. 96), Clement of Rome mentions the First Epistle to the Corinthians and speaks of the «Words of the Lord Jesus». Around the beginning of the 2nd century, the epistle of Barnabas (an apocryphal book not retained in the canon) quotes Jesus« words: »There are many called and few chosen«, declaring »it is written".

Various testimonies from the first half of the 2nd century show that the Epistles of the apostles were read in churches (Justin the Martyr, early 2nd century, speaks of «memoirs of the apostles and their disciples»).

The Bible, an exceptional book: it is estimated that over 4.7 billion Bibles (complete or partial) have been printed to date. Recently, in one year, more than 50 million complete or partial Bibles were distributed. «Every year, the Bible is the bestseller of the year,» says The New Yorker magazine. The Bible has been translated, in whole or in part, into more than 2,400 languages. More than 90 % of human beings have access to at least a portion of this book in their own language. Andrey Armyagov.

From church to church

It took some time for the various books that make up the New Testament to become known to all the churches of the Roman Empire. Communications were good, but slow. The books could only be copied by hand, which was laborious work.

And yet, little by little, the Gospels and Epistles began to circulate in the churches. Collections of the apostles' writings were built up, mainly in the great Christian centers of Rome, Alexandria, Antioch, Caesarea and Ephesus. Soon, all the books we know were grouped together and spread throughout the Empire. Quotations from almost all the books of the New Testament can be found in the works of Christian authors around the middle of the 2nd century.

Non-canonical Christian books

It should be pointed out, however, that in some churches other books were known which were not included in the New Testament canon.

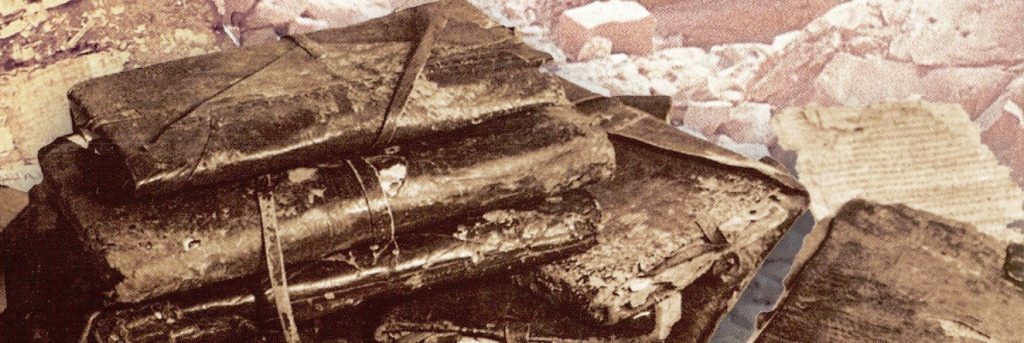

We know this, generally through quotations, since the complete text has often been lost; other Gospels were written, in addition to those of Matthieu, Marc, Luc and Jean. One of them, the «Gospel according to Thomas», is now better known to us, as a copy of it was found in a Coptic translation in December 1945 at Nag Hammadi in Upper Egypt. This is a Gnostic collection of sayings by Jesus of Nazareth, some of which reproduce passages from our Gospels; elsewhere, apocryphal gospels are quoted («Gospel according to the Hebrews", for example); however, some of Jesus' sayings are unpublished. The book is thought to have been written in Syria in the 2nd century.

Image opposite: the discovery of several Coptic codices at Nag Hammadi, Egypt © DR.

- The epistle of Clement of Rome to the Church of Corinth (c. 96). Clement was inspired by the teachings of Paul, James and Epistle to the Hebrews. His letter was read at services held by the Church of Corinth around 170.

- The Didaché (or Teaching of the Twelve Apostles) is a collection of precepts of Christian morality and instructions on baptism, the Lord's Supper and pastors, dating from the end of the 1st or beginning of the 2nd century.

These books enjoyed a certain esteem in many churches, since some Christian authors of the 2nd and 3rd centuries classified them as Holy Scripture.

Canon formation

It wasn't so much the existence of these different books as the position taken by certain dissenters that forced the Church to define the New Testament canon.

Two opposing errors threatened the Church:

- That of Marcion (known as of Pontus or Sinope, circa 85 - 160), a dualism that rejected the Old Testament, attributed to a God other than that of Jesus of Nazareth. He kept only Luke and Paul from the New Testament (the other books «seemed too Jewish» to him). To counter his doctrine, Doctors of the Church such as Irenaeus of Lyons (between 177 and 202) affirmed the inspiration of the entire New Testament.

- Conversely, Montan of Phrygia (c. 157/171), claiming to be inspired by the Holy Spirit and practicing the glossolalia *, He added to the recognized Scriptures «his prophecies» published in writing. The Church of the time had to draw a line in the sand.

* Phenomenon described in Acts 2:5/7. The glossolalia (from ancient Greek γλῶσσα / glỗssa, language« and λαλέω / laléô, is the ability to speak or pray aloud in a foreign language (xenolalia) totally unknown to the speaker.

The first certain list of books received is the «Canon of Muratori», a Latin document dating back to around 170, unfortunately in poor condition. It tells us which books were received as inspired by the Church of Rome in the second half of the 2nd century. The Epistle to the Hebrews is not quoted (the state of the text makes it impossible to know whether Jacques and II Pierre are included).

At the beginning of the 3rd century, Clement of Alexandria wrote a commentary on all the Books of the New Testament, with the exception of Jacques, II Pierre and III Jean.

By this time, the vast majority of churches had received all the New Testament books. Here and there, doubts remain about this or that book, mainly Jacques, II Pierre, II and III Jean, but also Epistle to the Hebrews (anonymous author), especially in the West, while in Palestine it is the Apocalypse in question. Other books, such as Clement of Rome, The Pastor of Hermas, the Didache, the Apocalypse of Peter are considered useful, but not inspired (as the theologian Origen declared in the 3rd century).

Gradually, all the churches came to agree on which books should be recognized as authoritative and which should be rejected. In the 4th century, the New Testament was officially and definitively established. In 367, Athanasius of Alexandria used the term «canonical» to designate the 27 books of the New Testament. At the Council of Carthage in 397, these same books were declared «Divine Scripture». It was decreed that only these books were to be read in church and retained as Holy Scripture.

It should not be forgotten that the authority of these books, with a few exceptions, had been established in almost all churches for a long time already. The Council of Carthage merely recognized this state of affairs.

To access the page from the New Testament canon of Scripture →

The criteria of canonicity

On what basis did the early Church distinguish between inspired and uninspired books?

This discernment was based on the following three criteria:

a) The consensus of all the churches: books that were read everywhere and whose authority was recognized in almost all the churches were admitted to the canon. This shows that the authority of the New Testament was self-evident, before any official declaration.

Some New Testament books have been more difficult to accept here and there. But these are exceptions, and the churches that hesitated eventually agreed with the majority. There are various reasons for this hesitation: in the case of Jude, II Pierre or III Jean, But it was their brevity that made them of little importance. They were rarely read in worship, and were less readily circulated. The Apocalypse was so different from the other books of the New Testament that it aroused suspicion. Where there was uncertainty as to whether its author was the apostle John, people remained reserved. It was also because the (anonymous) author was unknown that Epistle to the Hebrews has, for some, remained on the bangs of the canon. This brings us to the second criterion.

Image opposite: Jean Calvin, born on July 10, 1509 in Noyon (Picardy) and died on May 27, 1564 in Geneva, was a French theologian, an important reformer and an emblematic pastor of the 16th-century Protestant Reformation, notably for his contribution to the doctrine of Calvinism. © Morphart Creation. 1814709665.

c) The spiritual value of these books. Calvin, for example, wrote: «God, by His admirable counsel, has ensured that by public consensus, all other writings having been repudiated, only those remain in which His majesty shines forth». This criterion may seem subjective.

How can we be sure that we are not mistaken in preferring one book to another, in discerning the divine majesty? And yet, hindsight shows that the Church of the first centuries was not mistaken. The apocryphal Gospels, for example, portray Jesus as a «miracle-worker», often gratuitous, rather than the One who reveals the Father's love. Non-canonical books, while sometimes containing useful teaching, fall back on legalism (the Didaché), or in uncontrollable visions (The Pastor of Hermas).

The «deuterocanonical» and «apocryphal» books and the case of the Vulgate

The «deuterocanonical» books are those included in the Old Testament by the Catholic and Orthodox Churches, but which are not part of either the Hebrew Bible or the Protestant version. The books of the Hebrew Bible are described as protocanonical, i.e. of the first canon, while the «deuterocanonical» books are, according to the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Churches, of the second canon, according to the Greek language. deuteros «This is because they recognize their canonical and secondary character.

The decision to officially add certain books to the Catholic canon was taken in 1546, at the Council of Trent, whereas the Orthodox canon has always followed the Septuagint canon.

Judaism and Protestantism do not regard these books as inspired and refer to them as «apocryphal» (from the Latin aprocryphus, from Greek apokruphos, The term «secret» refers to a writing which, "purporting to be a book inspired by God, turns out to be a forgery and is not part of the Jewish or Protestant biblical canon" (Larousse French Dictionary).

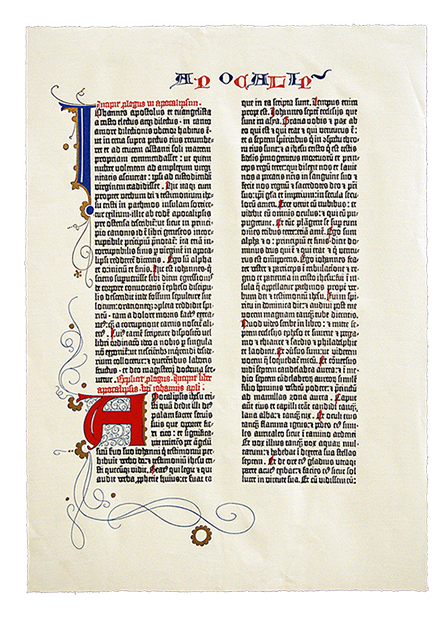

The Vulgate

The Vulgate

The Vulgate is a Latin version of the Bible, originally translated by Jerome of Stridon at the end of the 4th century directly from the Hebrew text of the Old Testament and from the Greek text of the New Testament, to which Jerome and his successors added adaptations of the Old and New Testaments. Vetus Latina («Old Latin [Bible]»), an older version translated from the Greek of the Septuagint.

Image opposite: a facsimile of the first page of the Book of Revelation printed by Gutenberg, circa 1454 © Collection Théo Truschel.

Diffused mainly in the West, it underwent several versions and evolutions, including those due to Alcuin in the 8th century and Erasmus in the 16th century, before being fixed by Pope Clement VIII in 1592, in a version known as «sexto-clémentine», which was authoritative in the Roman Catholic Church until 1979.

In 1454, Gutenberg reserved the honor of being the first printed book for the Vulgate.

The latest revision, promulgated in 1979 by John Paul II, is known as the «Neo-Vulgate».

Find out more

TRUSCHEL Gisèle and Théo, The Bible, the making of a book.

History and Archaeology Collection.

“La Bible, formation d'un livre” (The Bible, the formation of a book) includes information as close as possible to the most recent discoveries. Théo Truschel's knowledge of history and archaeology, his previous editing of the reference work “La Bible et l'archéologie” (Éditions Louis Faton), and his many contributions to magazines, leave no doubt as to the quality of the work that emanates from his research. His wife Gisèle, a history teacher, is a more than legitimate co-author in this editorial work. Gisèle and Théo Truschel have succeeded in making this book attractive, accessible and useful for all those who have questions about the origins of the Bible, an essential worldwide bestseller and a source of faith for humanity. (Fabio Morin)

Éditions Viens et Vois, December 2023, Lyon.

Image opposite: the last two pages of Psalm 151. Coptic Patriarchate Library, Egypt. Twelfth-century manuscript in Coptic and Arabic © Théo Truschel.

Image opposite: the last two pages of Psalm 151. Coptic Patriarchate Library, Egypt. Twelfth-century manuscript in Coptic and Arabic © Théo Truschel.

The Vulgate

The Vulgate