Bible, History, Archaeology

History,

Archaeology

Home >

Bar Kokhba,

correspondence

Contents:

New discovery - Introduction - Archive lots - The Ein Guedi region - TO FIND OUT MORE

New discovery

When Yadin's turn came, he projected to the audience a photograph of an ancient manuscript recently found by his teams in one of the Judean caves. He read the first line of the Aramaic text: «Shimeon Bar Kosiba, Chief of Israel». The discovery was a bombshell. The radio stopped its evening broadcast to announce the news. Israel had found undisputed traces of its history going back more than 1,800 years.

In a few words, the last president (nassi) of Israel spoke to the new president of the Jewish state, which had just been reconstituted thanks to the vote of nations at the UN on November 29, 1947.

Image opposite: Yitzhak Ben-Zvi (1884-1963). He was the second President of the State of Israel from December 8, 1952 to April 23, 1963. He played a decisive role in the fields of labor, defense and guarding the country. Public domain.

Introduction

Image opposite: coins under Hadrian, Judea, 136 AD.

to celebrate the new settlement replacing the city of Jerusalem.

Inscription: COL[ONIA] AEL[IA] CAPIT[OLINA] COND[ITA]. Foundation of the colony of Aelia Capitolina © DR.

Historians have at their disposal a fragmentary corpus of documentation rewritten through a Christian prism, a few ancient artifacts and a Talmudic tradition that debated Bar Kokhba's messianic nature. What emerges is the image of a leader who successfully opposed the Roman legions for at least three years. So much so, that in one of his statements to the Senate, Emperor Hadrian had to acknowledge the extent of the disaster (see Dion Cassius, Roman History, Book 69).

However, with the fall of the fortress of Bethar on 9 Av and the death of Bar Kokhba, Judea changed its name by imperial order to become Syria Palaestina. Hadrian also ordered that the city of Jerusalem, renamed Aelia Capitolina, was emptied of its Jewish inhabitants. The exile began.

Archive lots

Two archives of the Jewish leader's wartime correspondence have been found in caves in the Judean desert. They shed new light on the conflict. A first group of documents from Wadi Murabba'at (11 km north of Ein-Guedi) was identified in the early 1950s. A number of manuscripts resold by the famous Kando antiquarian alerted historians. They decided to trace the origin of the looting by following several members of the Ta'amireh Bedouin family, who were then criss-crossing the no-man's-land between Jordan and Israel. The caves looted in the Wadi Murabba'at left behind a number of documents that the expedition led by Père de Vaux was able to publish a few years later. Among the manuscripts, two letters are signed by Bar Kokhba.

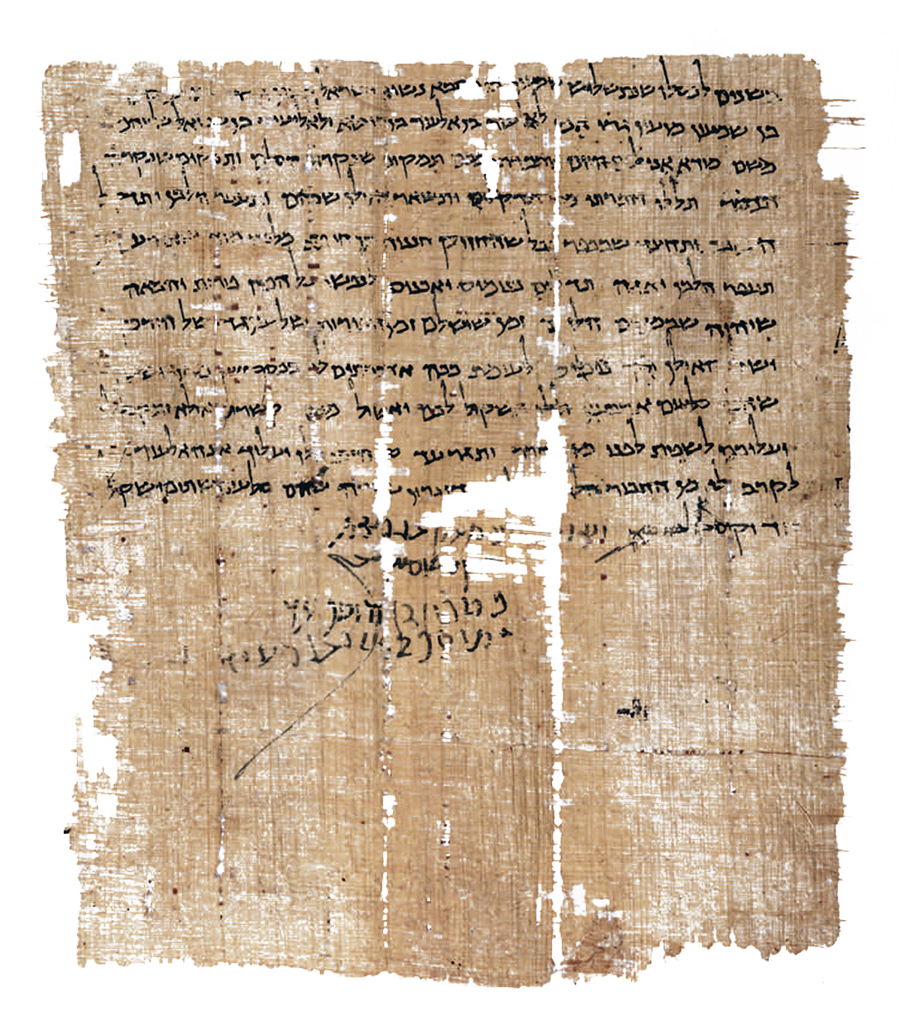

Opposite: Bar Kokhba papyrus 46, 5/6 Hev 46.

Scroll subject: a simple notarial deed, signing a lease. Discovered at Nahal Hever, the «Cave of Letters», in 1961. This ancient lease signature is dated «2nd of Kislev, in the third year of Simeon Bar Kosiba, (Bar- Kokhba), Prince of Israel», i.e. around November 134 CE.

Israel Antiquities Authority Collection.

In all, some fifteen letters from Bar Kokhba have been found and identified in two different contexts. Most are written in Aramaic, but five are in Hebrew and two in Greek. They are not dated. It is therefore difficult to know at what point in the conflict they refer.

The Wadi Murabba'at lot corresponds to part of the correspondence addressed to a Bar Kokhba commander, Yeshua ben Galgoula. He was in charge of a “camp”, i.e. a military region still poorly identified to this day. A Greek remarriage contract of his own sister, Salome, in the archives, however, provides a clue. The document is dated before the conflict, in year 7 of Hadrian's reign, i.e. 124 in today's reckoning. The deed was drawn up in the Herodium district near Bethlehem, and Yigael Yadin believes that Yeshua's territorial responsibility probably lay in this region. The Wadi Murabba'at is a natural outlet from the area to the Dead Sea.

Among the documents found, we learn of the existence of two presumably civilian administrators at Beth Mashko, dependent on the military authority embodied by the “camp chief” Yeshua ben Galgoula. They ask him to purchase a cow. This text seems to indicate that local power was split between military and civil affairs. The two authorities communicate with each other directly, without going through the central authority. The other important fact concerns the military situation on the ground. Incidentally, we learn that the “Gentiles”, in this case probably the Romans, are very close and prevent the arrival of the administrators to authenticate the purchase. Unfortunately, the letter is undated, but its content is surprising. Indeed, the front is not far away, and yet the civil authorities are anxious to plead the cause of one of its inhabitants for a purchase.

Image opposite: a new piece from the Bar Kokhba revolt unearthed in March 2020 near the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Israel Antiquities Authority.

The second batch of archives provides more information on this subject, since it refers to the participation of foreigners on the side of the Jews against Roman rule, particularly Nabataeans (letters from Soumaios, Thyrsis and Ailianos), confirming the indications given by Dion Cassius on the regional scope of the war. The correspondence found at the Nahal Hever mainly concerns the activities of Jonathan son of Bayan and Masabbala son of Simon, two military leaders from the Ein-Guedi region. Relations seem to have been difficult between the headquarters and the regions controlled by the regional commanders. It is not uncommon to see orders accompanied by threats in Bar Kokhba's remarks. Relations seem so difficult with the military commanders that we found a letter addressed to a certain Yehuda bar Menashe asking him to act as intermediary to bring in the four species of plants from the area controlled by the Ein-Guedi commanders. Bar Kokhba seems to have lost faith in them. The exasperation is palpable in many of the letters.

The Ein Guedi region

The Ein-Guedi region also proved to be a source of supplies for Bar Kokhba's troops. We feel like we're behind the front line. It's a strategic zone. We see the commanders of the region being asked to send wheat, donkeys, salt and various agricultural products. But above all, they are the guardians of the region's aromatic plants, known throughout the ancient world for their quality. A stern reminder is made in this respect concerning laudanum.

Image opposite: a waterfall in the Ein Guedi nature park. © DR.

Despite the weakness of the military correspondence file (15 letters for at least three years of conflict), the letters do lift some of the veil on the logistics of the conflict. It seems to have worked, despite the slowness or unwillingness of the rear areas. The letters give us an idea of the extent of the conflict, making this war a regional struggle against the Roman presence. Finally, while most of the documents found are in Aramaic, one letter written in Greek gives us the exact name of the Jewish leader. His name is Shimon Kosiba. Since Greek transcribes all the vowels, we know exactly what he was called. We had to wait 19 centuries to find handwritten documents of the warlord. Rabbinic tradition evokes several names to better reflect on the nature of the Jewish hero. But it is Bar Kokhba's name that has remained in posterity, following in the footsteps of the Christian tradition fascinated by the notion of the star. Bar Kokhba, son of the star, also refers to a famous debate between the Sages on the messianic nature of the Jewish leader.

Many questions remain unanswered. How are we to understand the preservation of these archives, which are so unfavorable to military commanders? What exactly was the role of these military districts? Retreat zones to the south? Supply zones? Why didn't Bar Kokhba travel to these areas?

Why are fragments of the 12 Little Prophets to be found in these two caves? Who were the men found in the Nahal Hever caves not far from the archives? Finally, we had to wait almost two millennia to find the real nom de guerre of the Jewish leader. Above all, we note that the story of this war has been overshadowed by the peaceful discourse of a golden age, that of the pax romana of the second century.

Find out more

Marc Truschel, Judea from Vespasian to Bar Kokhba. Iudaea Capta.

Sources and readings. Building a story.

The investigation based on the literary corpus will take the reader on a long journey from the writings of Flavian Rome to those of the early Middle Ages. The book offers new perspectives through its historical analysis of the two conflicts that hit ancient Judea hard.

Presses Académiques Francophones. 270 pages.