Bible, History, Archaeology

History,

Archaeology

Mesha, king of Moab,

the stele

Contents:

The Moab stele - An eventful discovery - The stele painting and text - A royal victory stele - Text translation - An image of the Moab plateau - A probable mention of the expression «house of David».» - Image of damaged inner part - A new hypothesis and the answer - Decryption image - Collège de France video on the exhibition organized around the Mesha stele

The Moab stele

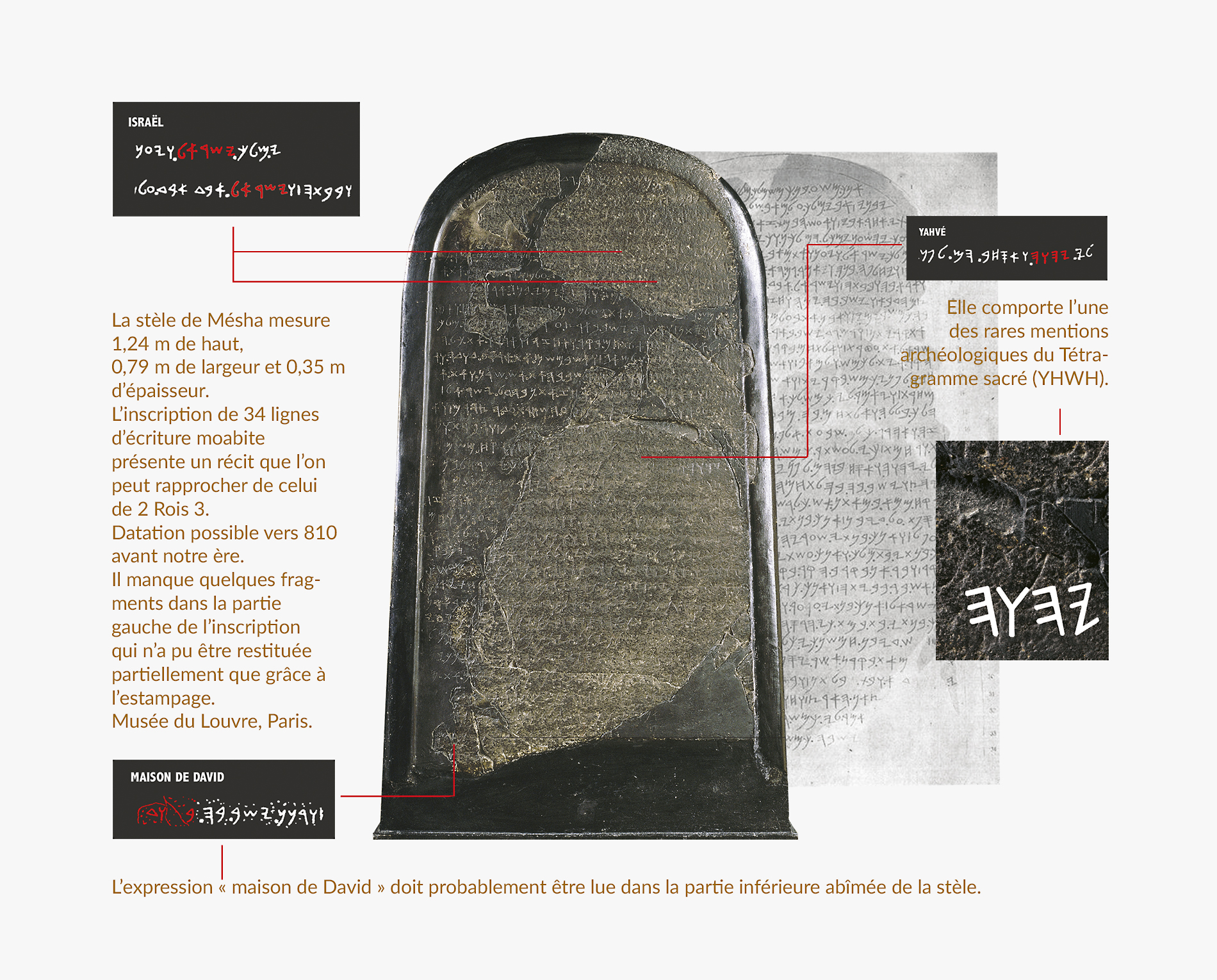

Written to the glory of King Mesha, it celebrates important constructions and victories won over the kingdom of Israel after Ahab, descendant of Omri. The written mention of ’Israel« is the oldest known occurrence in the Levant. Dhibân, the ancient Dibôn, where the stele was discovered, was the capital of the Moab kingdom on the eastern shore of the Dead Sea.

Image opposite: the desert of Wadi Rum. One of the deserts of the Bible, stretching east from the Dead Sea to the south of the land of Moab. Marc Truschel.

An eventful discovery

It was discovered on the knoll of the village of Dhibân in South Jordan, east of the Dead Sea. Its ruins cover the slopes of two mounds

On August 19, 1868, on this second mound, a sheikh from the Beni Hamideh tribe drew the attention of Alsatian missionary Frederick Augustus Klein of the Anglican Christian Missionary Society in Jerusalem to a black, oval-topped block of stone emerging from the dusty ground. On one side is an inscription containing the remains of thirty-four lines of regular Moabite script, close to ancient Phoenician and Hebrew, prompting F. A. Klein to copy a few words and send them to the Prussian consul in Jerusalem.

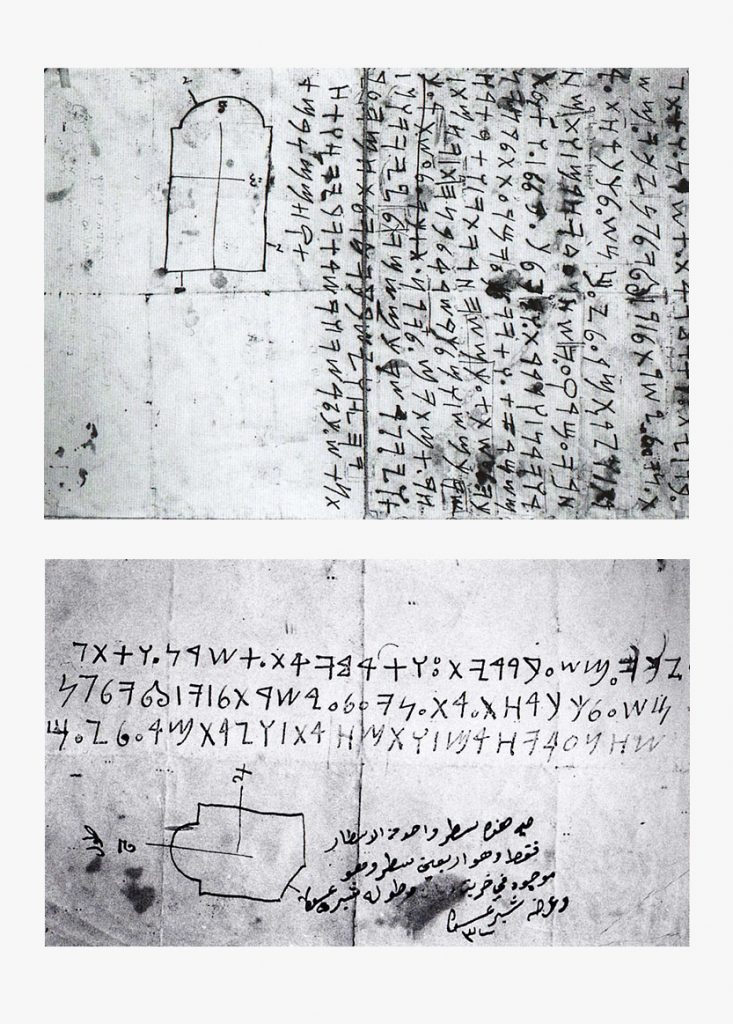

Charles Clermont-Ganneau hears the news 1, orientalist drogman (interpreter) and chancellor of the French consulate in Jerusalem. The latter arranged for an emissary to make a schematic copy in October 1869, enabling C. Clermont-Ganneau to recognize the stele's importance and early date. He then sent a second intermediary to make a stamping, in December 1869.

Image opposite: copies of the Mesha stele by Sélîm al-Qâri. Musée du Louvre, Department of Oriental Antiquities.

Perhaps hoping to make a profit, the Bedouins heat the stone to a very high temperature, then pour very cold water over it, break it into numerous pieces and distribute them to the main chiefs of their tribe.

Subtle negotiations enabled C. Clermont-Ganneau to recover the two main fragments as well as a few fragments, while others went to the great British archaeologist Captain Warren and the Palestine Exploration Fund Society, as well as to Professor Schlottmann of the German Oriental Society (Deutsches Morgenlandisches Geselleschaft). On learning that the Louvre had acquired the pieces collected by C. Clermont-Ganneau, the Palestine Exploration Fund generously donated its fragments to him, and Professor Schlottmann's daughter offered hers in 1891. C. Clermont-Ganneau then partially reconstructed the monument, with the help of stamping, and had it placed in the Musée du Louvre in Paris in 1873.

1. Charles Clermont-Ganneau (1846-1923), professor at the Collège de France, member of the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres.

A royal victory stele

Image opposite: a carabao seal and its imprint: “belonging to Kemosh'our”. 8th century B.C. Deutsch and Heltzer. 1997. 109.

The inscription delivers the earliest occurrence of the word Israel in the Levant and is the most detailed documentary source on the kingdom of Moab and its rivalry with the kingdom of Israel at the time of king Omri and his successors.. It could correspond to a campaign carried out after that of the coalition 3 against Moab, mentioned in 2 Kings 3,4. This interpretation would demonstrate that the stele was indeed erected after this campaign and the fall of the Omrid dynasty (Israel was annihilated forever! line 7) and even after Jehu's coup d'état. The stele also gives the name of Moab's great god, Kamôsh, whose spiritual «son» Mesha claims to be.

Mesha's victories and constructions mainly concern the territories north of Moab, close to Israel's northern borders.

Mésha boasts of having taken the cities of Atarot (tribe of Gad), Mêdabâ, Nébo, Yahaz, and of having built or rebuilt Baalme'ôn, Qiryatên, Aroër, Bêt-Bamôt, Bezer, Diblatên, all ancient toponyms mentioned in the Bible.

At the bottom of the present stele begins a second part that evokes Mesha's victories in the South, with the conquest of the city of Ḥôronên against the «house of David» (damaged end of line 31), i.e. the kingdom of Judah. Unfortunately, the rest of the inscription had already disappeared by 1868.

2. Reading the last line presupposes the existence of at least one additional line.

3. King Yoram of Israel, King Jehoshaphat of Judah and his Edomite vassal.

Text translation

Today, the stele has significant missing parts, probably gone forever, and has been partially completed in plaster thanks to the stamping that was carried out before its partial destruction.

Image opposite: a stele discovered at Shihân, depicting a warrior god (Kamosh, storm divinity?) brandishing a spear in the customary attitude of Levantine steles. Musée du Louvre. Théo Truschel.

«I am Mesha, son of Kamosh, king of Moab, the Dibonite. My father reigned over Moab for thirty years and I became king after my father. I made this high place for Kamôsh in Qarhôh because he saved me from all the kings and made me enjoy the sight of all my enemies. Omri had been king of Israel and had oppressed Moab for a long time because Kamôsh had become angry with his country. His son had also succeeded him: «I will oppress Moab!» In my time, he had spoken thus, but I enjoyed the sight of him and his dynasty: Israel was annihilated forever! Now Omri had taken possession of the land of Madaba and colonized it in his time and for half the time of his sons: forty years, but Kamosh restored it in my time. I rebuilt Qiryaten. The Gadians had always lived in the land of Atarot and the king of Israel had built Atarot for himself, but I fought against the city and took it; I killed all its people and the city belonged to Kamosh and Moab; I brought back the altar of burnt offerings of their beloved god and dragged it before Kamosh to Qeriyot. I installed people from Sharon and Maharot. Kamôsh said to me, «Go, take Neboh over Israel!» and I went by night. I fought against it from dawn to noon; I took it and killed all its inhabitants, seven thousand men and boys, women and girls and even the pregnant women, for I had vowed them to Ashtar-Kamôsh. And I took the altars of burnt offering from Yahweh (YHWH) (the oldest attestation of this divine name) and dragged them before Kamôsh. The king of Israel had built Yahats and colonized it by fighting against me, but Kamôsh drove him out before me. I took from Moab a troop of two hundred men in all, carried them against Yahats and took it to annex it to Dibon. I built Qarhôh, the wall of the parks and the wall of the citadel. I built its gates and I built its towers. It was I who built the royal palace and it was I who made the dikes of the reservoir for the waters inside the city. There was no cistern inside the city in Qarhôh, so I said to all the people, «Make yourselves each a cistern in your house!» I had the prisoners of Israel dig the ditches for Qarhôh. I built Aroer and I rebuilt Bet Bamot because it was destroyed. It was I who rebuilt Bezer, for it was ruins with fifty men of Dibon, for all Dibon was subject to me. It was I who ruled over the hundred cities I annexed to the land. It was I who built the temple of Madaba and the temple of Diblaten and the temple of Baalmeôn, and I erected my sanctuaries there to sacrifice the small livestock of the land. As for Hôronen, dwelt there... and Kamôsh said to me, «Go down, fight Hôronen!» And I went down and fought against the city and took it. And Kamôsh gave it back in my time, and I went up from there ten... It was I who...»

(Translation by A. Lemaire, 1986). With his kind permission.

The plateau of Moab and the Arnon (Wadi al-Mawjib), which often served as a border: it separated the Moabites from the Amorites, then, after the Hebrews settled there, Moab from the Israelite tribes of Reuben and Gad. Image © F. Higer.

A probable mention of the expression «house of David».»

The expression «house of David» should probably be read in the damaged lower part of the Mesha stele. 4. Indeed, at the end of line 31, we read BT[D]WD and, according to the context, this expression refers to the kingdom of Judah, which controlled the city of Horonayim and part of the territory southeast of the Dead Sea. BTDWD means that David was the founder of the dynasty reigning in Jerusalem, which is entirely in line with the historiographical tradition of the Bible.

The Mesha stele contains one of the few archaeological references to the sacred Tetragrammaton (YHWH).

4. Hypothesis by Professor André Lemaire, Director of Studies at the École pratique des hautes études, section des sciences historiques et philologiques.

A new hypothesis and the answer

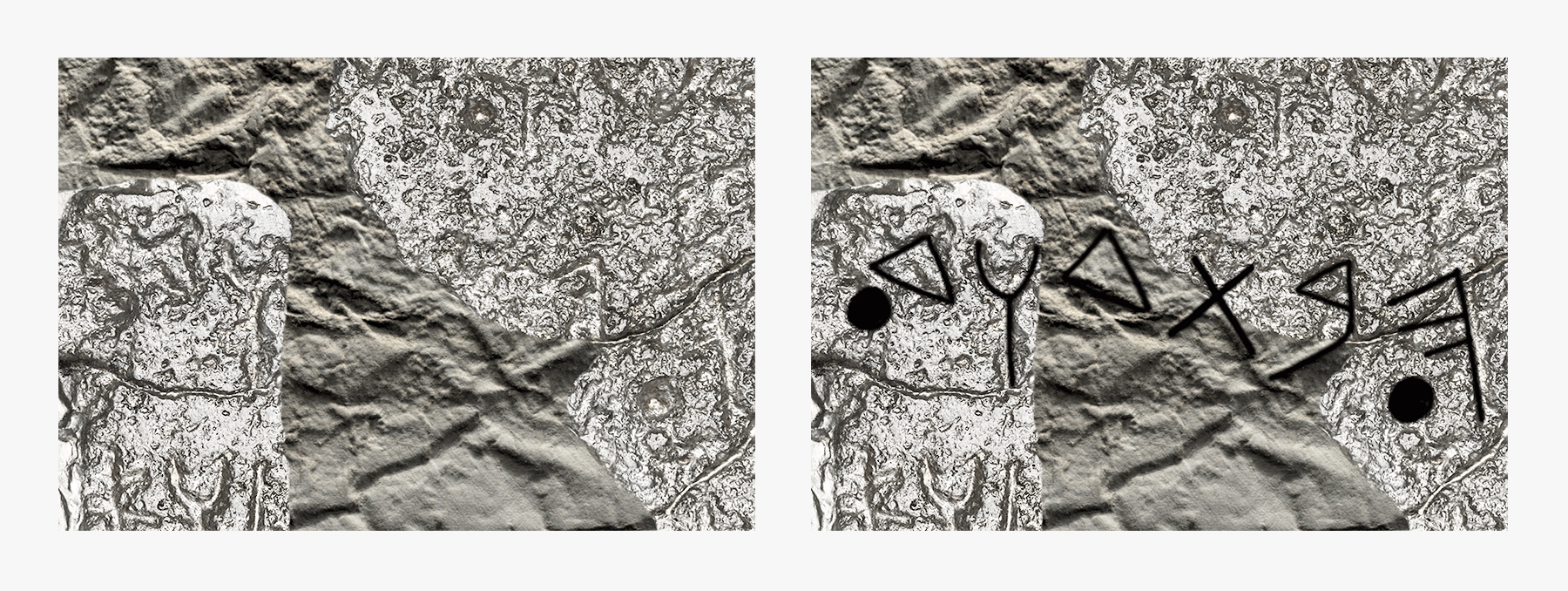

To mark the 150th anniversary of the Mesha stele, it has been restored, with new images of the fragments and the backlit, high-resolution stamping.

Based on this last cliché, in the latest issue of the magazine Tel Aviv, Nadav Naaman, Israël Finkelstein and Thomas Römer refute the reading of line 31 (badly damaged) proposed by André Lemaire, director of research at the École Pratique des Hautes Études (EPHE), namely that of the expression BT [D]WD, Beit David which, taken in its dynastic sense, means «house of David».

According to the three specialists, it would be better to read/restore «Ba[laq]», the name of the king of Moab who, in the book of Numbers, commands the prophet Balaam to curse Israel (Numbers 22-24). In their opinion, the reading/restitution Ba[laq] would be more in line with the new cliché.

Michael Langlois, a specialist in computer-aided Hebrew paleography and epigraphy, was quick to react to this new interpretation: the stamping is difficult to read and, in his opinion, they have misinterpreted it. Apparently, they haven't examined the original at the Louvre, and are unaware that the stele and the stamping have already been photographed recently (2015) in RTI (Reflectance Transformation Imaging), which makes it possible to study them by easily playing with the various possible origins of the grazing light and facilitates, in general, the paleographic study of incised or relief inscriptions. In fact, to refute the BT[D]WD reading, the three specialists rely above all on a so-called philological argument, namely that BTDWD, «the house of David», is a collective that cannot be the subject of the verb YŠB, «to dwell», even though there are examples of this in the text of the stele itself and in the Hebrew Bible.

Based on the RTI photos, in his article published in the latest issue of Semitica, Michael Langlois confirms André Lemaire's proposal. He even suggests that, thanks to these photos, certain traces of the Louvre stamping can be identified as traces of the first D which disappeared when the stele was blown up by the Bedouins, and is hardly visible on the stele itself today.