Bible, History, Archaeology

History,

Archaeology

Home >

Massada and Rome, the siege,

70-74 A.D.

Contents:

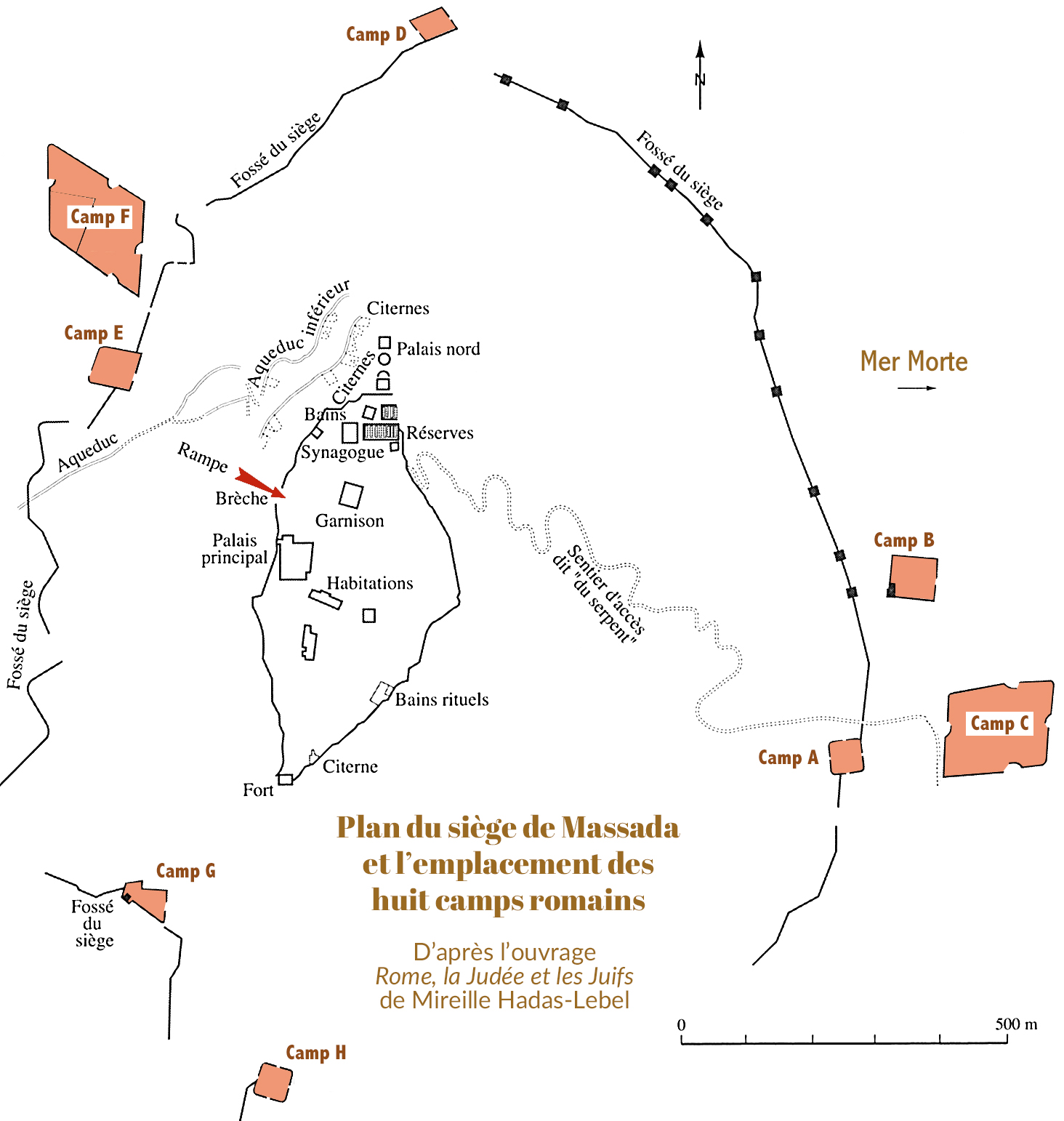

The story - For a chronology - Map of Masada and the eight Roman camps - The seat - The defenders - Conclusion - TO FIND OUT MORE

Masada is much more than just an astonishing site of incredible Herodian architecture; it's the story of a tragedy recounted in the form of a tribute by the historian Flavius Josephus. It recounts the siege and fall of the citadel taken by the armies of the Roman legate Flavius Silva. It was the last bastion of Jewish resistance to the Roman oppressor after no less than seven years of war.

The story

The story

The history of the site of Masada has been handed down to posterity thanks to the success of a book published in 75/79, the Jewish War. It was passed on to modern readers by the powerful Christian historiographical tradition, which took off as early as the 4th century. The author of the work, Flavius Josephus, who became famous thanks to the Christians, devoted many lines to the siege undertaken by the Roman army in front of the citadel of Masada.

Image opposite: model. Reconstruction of Herod the Great's three-storey northern palace overlooking the Judean desert © Image Berthold Werner.

Rome thus put an end to a long war in Judea, which had begun under the reign of Nero in 66. Indeed, it was neither the capture of Jerusalem in August 70, nor the triumph in Rome of Vespasian, the new emperor, with his son Titus in the summer of 71, that marked the end of hostilities in Judea. It was not until 73, or even 74 according to some historians, that the last rebel stronghold fell. Its fall, according to the historian Flavius Josephus, signalled the end of fighting in Judea. The troubles moved further south, to Egypt and as far as Cyrenaica.

A fortress perched on a granite pedestal overlooking the desert near the Dead Sea, Masada, with its restored ruins, has become a modern pilgrimage site for Israelis and tourists alike. The ruins offer an extraordinary view across the Judean desert to the Dead Sea (in the background). 619534733 Leonid Andronov.

For a chronology

Image opposite: view from the north of the fortress of Masada, King Herod's residence. The three levels are linked by a staircase. Andrew Shiva.

According to Flavius Josephus in the Jewish War, In the early hours of the conflict, the citadel was occupied by a group known as “les Sicaires”. Quite a program! Since this name refers to a sharp knife with a curved blade, the sica, the weapon of assassins. They drove out the Roman garrison that had settled there, and remained there until the end of the war. After the assassination of Menahem, their dynastic leader in Jerusalem, who was in the midst of factional struggles for power and leadership in the war against Rome, his brother Eleazar ben Yair took command of the fortress until its end. According to Flavius Josephus, the Sicars were determined to control Jerusalem. They killed the High Priest, burned various symbols of power - royal palaces and archives - but this attempt at control was a resounding failure and, on the death of their leader, they had to retreat to Herodium, Macheronte and Masada.

What role did Masada play in the Jewish war effort? Flavius Josephus tends to marginalize it, saying that since Menahem's death, this group had lived apart from the major operations against Rome. Yet many of the coins minted in Jerusalem during the war have been found there, proof of direct contact with the heart of the revolt. What's more, it's hard to believe that the Sicarii, whose sedition against central power dated back at least to the time of Herod the Great, would have been content to sit quietly on top of Masada and wait for the Romans.

Image opposite: the assault ramp, seen from the top of the plateau, built by the Romans to reach the fortress palace. © Posi66.

Historians are at a loss to know exactly how long the siege lasted. The only date given by Flavius Josephus concerns the fall of the city, on a certain 15th Xanthicus, a Greek month corresponding to the Jewish month of Nissan, when the Jews celebrated Passover. But which year? The text is almost silent. In any case, it's not explicit enough. You have to go back further in the book to see that the last indication of the year is that of 73, the fourth year of Vespasian's reign, beginning on July 1, 72 and ending on June 30, 73. But the two inscriptions tracing Silva's career, found in his hometown in Italy, show that he was still a praetor in the spring of 73, and therefore did not yet have the senatorial level required to be a legate and lead this army! He could not have mounted his expedition against Masada so quickly, especially as before his appointment as legate - which takes time - he was exercising his praetorship in Italy. The controversy over the chronology of the siege is therefore raging among historians. And it's not the discovery of this letter found on the Massada plateau, sent to a certain Iulius Lupus, probably the Prefect of Egypt since February 73, that is likely to calm the debate.

Let's remember for now that we're at the end of a long war, and like all good storytellers, Flavius Josephus makes it one of the most important moments in his narrative.

The seat

The story of the siege would have fallen through history's famous trap doors had it not been for Flavius Josephus' lengthy description. Certainly, there are eloquent remains of Roman works, the construction of several military camps, the building of an encircling wall and the construction of a huge access ramp to the Masada plateau. But these remains would certainly have had less evocative power without the dramatic breath of Flavius Josephus' text, which builds tragedy around this story.

Image opposite: a reconstruction of one of the siege machines built by the Romans, for the film «Masada», shot on the actual site. It was directed by Boris Segal in 1980 © DR.

It seems that, given the extreme material conditions of the siege, legate Flavius Silva was forced to carry out a large-scale military operation, requiring all the armed forces present in the region. He could not afford to prolong the Roman presence too long below the citadel, which was extremely well supplied with food and water, as archaeological remains still prove. Historians estimate that there were between 8,000 and 15,000 Roman soldiers - including manpower - including 5,000 from the X legion. Fretensis. A quick calculation shows that it took almost 16 tons of food and 26,000 liters of water every day to keep this army going. This would explain the disproportionate preparation for the assault on Masada, with its eight forts and surrounding wall. We had to act quickly and forcefully.

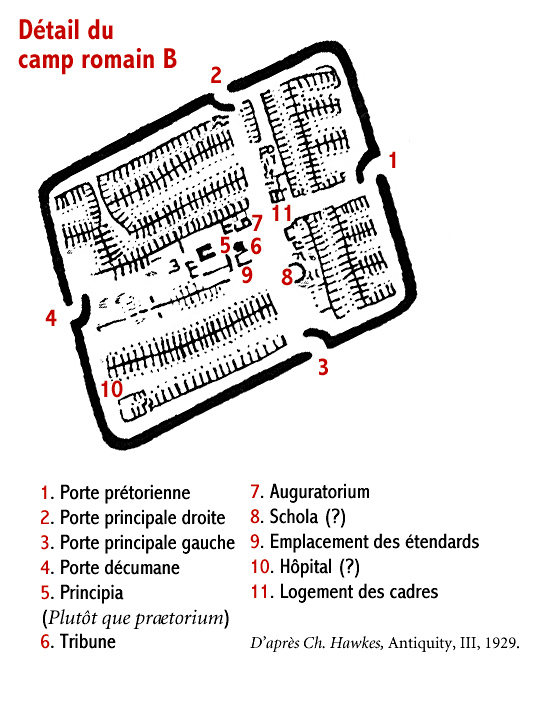

Image opposite: detail of one of the eight Roman camps set up around the rocky peak of Masada © Ch. Hawkes.

We can imagine - and this is the thesis of Josephus' speech - that one of Rome's main enemies in the region was up on this plateau. It seems that the deaths of John of Gischala and Shimon bar Giora in Rome were not enough to put an end to the hopes of the last Jewish fighters in Judea. Hope that was now to cease since Vespasian and Titus had triumphed in June 71.

Image opposite: traces, still visible today (left and right), of two of the eight Roman forts of the X Fretensis Legio that surrounded the site of Masada, preventing the besieged from escaping © Esther Inbar.

What historians understand about the siege, by cross-referencing information from the text with that from the field, is that once the wall had been built, all Roman effort naturally focused on the western flank of the fortress, the lowest and therefore weakest point of the site. It was decided to build a ramp to access a ledge at the top of the slope. The construction of assault ramps to carry artillery equipment is not new to the art of ancient poliorcetics. They can even be found on several occasions during the Jewish War, thanks to the text by Flavius Josephus. At Yodfat, Gamla or Jerusalem. The execution time for such attack devices was at least three weeks.

On this ramp, which has now been found virtually intact, a 30-metre-high, three-storey, iron-clad tower - the helipole - was erected, enabling them to get very close to the fortress wall and demolish it. Within range of the enemy's defenses, the Roman fighters could fire with pinpoint accuracy, protected as they were by their armoured tower.

Image opposite: excavations on the Masada plateau also uncovered these stone cannonballs, some weighing as much as 50 kg, used to defend against the Roman siege. Traveluya.com

It is difficult to say how the besieged defended themselves. A few cannonball-shaped stones weighing almost 50 kg have been found. But apart from a few weapons, we know nothing about the methods used by the Jews to delay the Roman advance. On a site later garrisoned by the Romans, it is extremely difficult for the archaeologist to distinguish between the weapons used by the Roman and auxiliary units and those of the besieged. But can we get an idea of who these warriors were? Archaeology has revealed some very interesting documents.

The defenders

While their numbers and demise are unknown, simply hypothetical, they did leave a few traces on the vast plateau overlooking the desert. The Herodian palaces were summarily converted into living quarters. Here and there, archaeologists have spotted new, lightweight partitions. More extensive modifications actually changed the purpose of some buildings. These include two ritual baths, miqvé, and a probable synagogue identified on the western flank of the Masada plateau. This is one of the oldest synagogues in Israel, and its layout bears a striking resemblance to later ones found in Galilee. A place of gathering, study and prayer, it has no sacred character; it is its occupants who give it its singular dimension.

Image opposite: Mosaic decoration on the floor of the entrance corridor to the baths in Masada's western palace © Gabi Laron, Institute of Archeology of the Hebrew University.

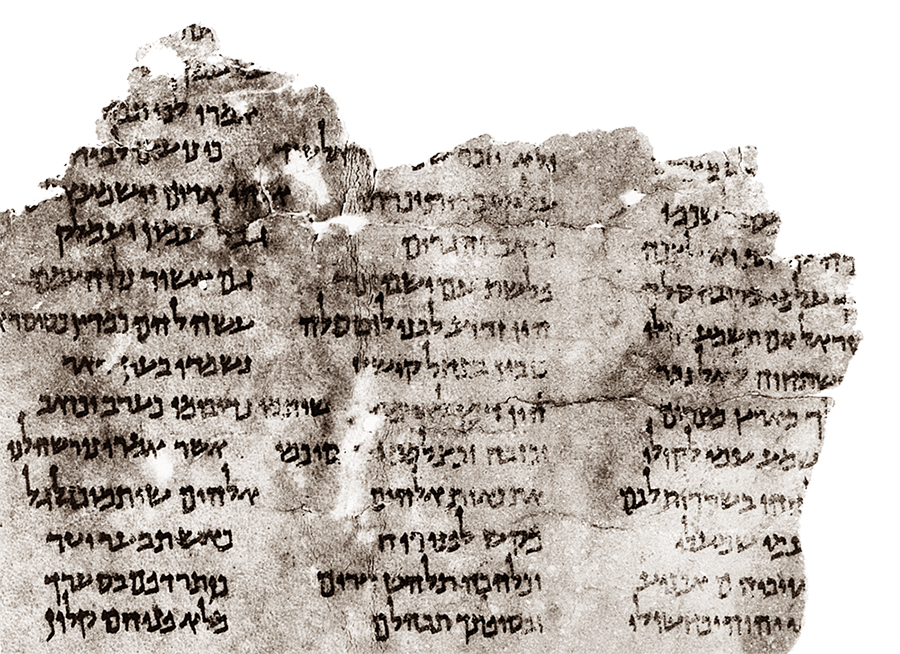

Fragments of biblical texts were found in a small cell at the back of the building. These were fragments of a parchment scroll containing passages from Deuteronomy (chapters 33 and 34, i.e. Moses' blessing to the tribes) and Ezekiel's famous chapter 37, about the vision of the dry bones. The pit was probably the gardenizah, a place where damaged sacred texts were carefully stored.

Many more documents were found in a building known as the “scroll casemate”, just ten meters south of the synagogue. Some of the scrolls were found torn, which archaeologists believe proves that it was the Romans who put them there in the first place. Despite this treatment, fragments of Psalms and other biblical passages have survived the ravages of time.

What's more, the teams of archaeologists led by Y. Yadin were stunned to discover texts that researchers had previously found only in the caves surrounding the Qumran site, and which the discoverers had been quick to describe as Essene; this sect is described by Pliny, Philo of Alexandria and, above all, by Flavius Josephus in his Book II of the Jewish War. Fragments of the Book of Jubilees (found in the tannery next to the west palace) or the Shabbat day hymn and a few other small fragments (apocrypha of Genesis and Joshua) raise huge questions for historians and philologists who see the Essenes as the authors of these sometimes obscure texts. Indeed, how can we explain the presence of these works on the Masada plateau, reputedly in the hands of the Sicars and not the Essenes?

Image opposite: discovery of a scroll fragment containing passages from Psalms 81 and 82 © Gabi Laron, Institute of Archeology of the Hebrew University, Jerusalem.

Armed with these very singular texts, many historians no longer hesitate to say that the Sicarii of Flavius Josephus present at Masada had been joined by representatives of the Essene sect. If we follow their reasoning, they may well have found them again following the destruction of their main site in 69. Archaeological traces found at the site of Khirbet Qumrân, 50 km away, which is, according to Essene theorists, the central location of the sect, show the installation of a solid fortress that was destroyed by the Romans. This is a far cry from an isolated place, populated by monks who forged no weapons and retreated into the desert. Especially since the Essenes are strangely absent from the conflict when we read the Jewish War. Flavius Josephus mentions only one Essene combatant in the entire history of the war.

Flavius Josephus' account of the siege of Masada, which has never been contradicted up to now, is suddenly shaken by these unusual scrolls. Historians are at a loss to find a rational explanation for these exceptional discoveries. They have undeniably reopened the debate on the origin of the texts, which is one of the other interests of the Masada site.

Since then, it has no longer been possible to limit our understanding of these works - which have a wide range of purposes and themes - to a single Essene reading. In particular, the traditional understanding of Essene writings does not coincide with the ancient, i.e. ancient and even medieval, discovery of various collections of works in the caves around Jericho, or more recently, in the 1960s, at Masada. It seems that we have to face up to the fact that there were real and profound reflections that shook Judaism at that time, expressed in all kinds of works that seem dishevelled to us today, but which were in reality no more than witnesses to the questions asked at that time in Judea and the Diaspora. And perhaps it's not necessarily useful to put all the blame on the frail shoulders of the Essenes to understand the vast debates that animated the discussions of the time.

Essenes? This hypothesis is quite plausible in absolute terms, but, as we now understand, it can no longer really be explained by the presence of these works of disputed authorship.

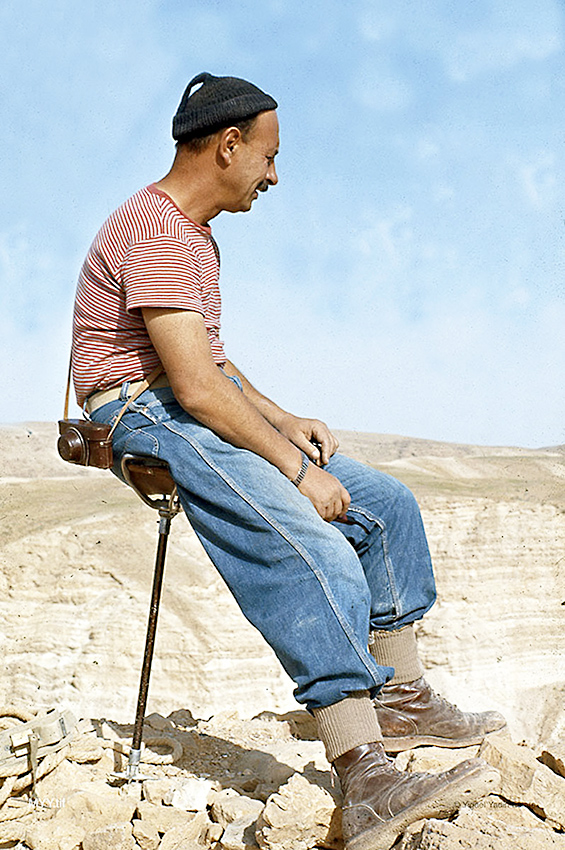

Image opposite: Yigaël Yadin (1917-1984), archaeologist, politician and high-ranking military officer in Israel. He was the son of the great researcher Eleazar Sukenik © Image Archaelogical Photographs Yadin's Productions.

How many were there? A thousand? as Flavius Josephus declares, even though he was absent from the fighting, but who seems to have drawn his inspiration from notebooks written during the battle? No one can say. Some names have been found painted on ostraca. Among dozens of characters found, we read of “the baker's son”, ben Hanahtom, or “the hunter” Tsaiyada or Onias and a certain Ben Yaïr. Names brought out of obscurity after hundreds of years of oblivion.

What seems more attested, however, are the sequences of the siege, the installation of the Roman troops, the encirclement, and the assault from the western side of the site. As for the chronology of the fighting, there is still considerable uncertainty.

Conclusion

Conclusion

Generally speaking, the reconstruction of the history of the siege is based almost entirely on what the medieval copyists of the text by Flavius Josephus have left us. We must therefore remain humble. We have already mentioned the many limitations and gaps in this text. As for the archaeological evidence, it is clearly too incomplete to embark on a meticulous historical reconstruction, which would be far too risky. We quickly reach the limits of historical narrative. On the other hand, the questions raised by the confrontation between the text and the archaeological evidence have brought to light a complexity of historical context that is not without interest for the researcher, for in the final analysis, the history of the siege of Masada has yet to be written.

Image opposite: an artistic illustration of a Roman general from the 1st century AD. © DR.

But Masada, far beyond its grandiose Herodian architectural achievements, its spectacular siege and its questioning of the historical context, has a third and most powerful dimension. This is its symbolic dimension. The strength of Josephus' text lies in its incredible discourse. In the form of a funeral tribute, a fiery Flavius Josephus has constructed a veritable plea for freedom, a freedom that was found in a freely consented death. This rhetoric, with its Greek accents, still resonates today. It transformed the site into a place of remembrance, the last bastion of Jewish resistance to Roman oppression.

Find out more

Mireille Hadas-Lebel, Rome, Judea and the Jews

Collection Antiquité/Synthèses.

Éditions Picard, 2009.

The story

The story

Conclusion

Conclusion