Bible, History, Archaeology

History,

Archaeology

The Hebrews,

the Hebrew language,

the paleo-Hebrew alphabet

After the biblical account of Creation and the Flood on earth, the Book of Genesis relates that at the beginning of the second millennium BC, a small group led by Abram (not yet called Abraham) left Ur and, after a stay in Harran in northern Mesopotamia, came to settle in Canaan, between the Jordan and the Mediterranean coast.

In 135 AD, following a merciless war against the Roman Empire, the ancient Jewish state disappeared.

The ancient history of the Hebrews is that of an existence that stretches between these two dates, over a period of around two millennia.

The Hebrews

A Hebrew group (Israel) appeared on the West Bank at the end of the 13th century BC, and a Hebrew kingdom, that of Saul, in the second half of the 11th century. It used the local Canaanite language and script, which gradually differentiated itself from Phoenician during the 10th century under the reigns of David and Solomon. The birth of a Hebrew scribal tradition would develop over the following centuries, in both the kingdom of Israel and the kingdom of Judah, until the fall of Jerusalem in 587 BC.

The Hebrew language

Hebrew is a north-western Semitic language spoken in ancient Palestine during the first half of the 1st millennium BC, in the territory of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah. It represents the natural evolution of the language spoken in the 2nd millennium BC: “Canaanite”, a development parallel to that of Phoenician with, in particular, the prepositional article (H-) and, unlike Phoenician, its use before a demonstrative.

The Paleo-Hebrew alphabet

Its script was the natural development of the 22-letter Canaanite linear alphabet of the second half of the 2nd millennium BC, alongside Phoenician. In fact, in the 11th-10th centuries BC, we can still speak of a “Canaanite” linear alphabetic script common to the whole of the Levant, or designate inscriptions from Palestine as “proto-Hebraic”, “proto-phoenician” or “proto-philistian” according to their location, as it is still virtually impossible to distinguish palaeographically between the various local scripts.

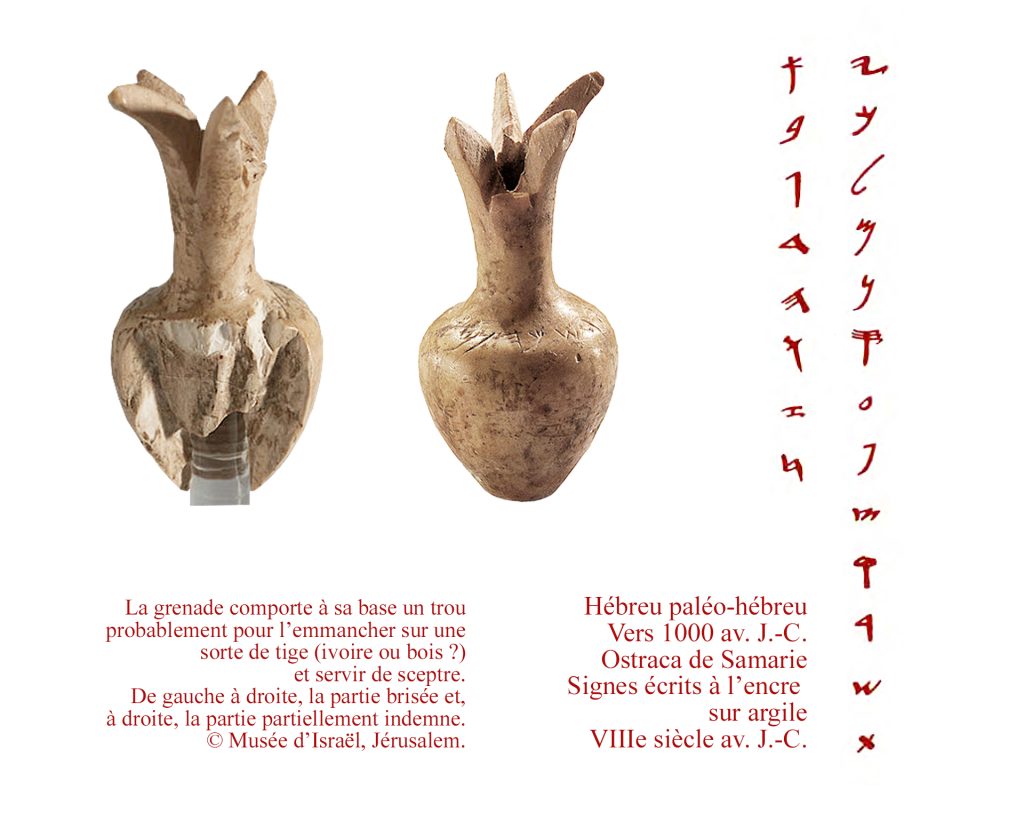

The pomegranate is an important element in biblical tradition which describes certain features of the Temple. We read that garlands of 400 pomegranates adorned the capitals of the two bronze columns that sat at the entrance to the sanctuary (1 Kings 7,20), and also, concerning the ceremonial tunic of the high priest: «a golden bell, a pomegranate, a golden bell, a pomegranate, on the sides of the robe all around». (Exodus 28,34).

Several “proto-Hebrew” inscriptions from this period have been found in the middle Jordan valley (Tell eș-Ṣarem/Tel Reḥov), in Samaria (Khirbet Tannin), in Jerusalem and its environs, in Shephélah (Gézer), Beth-Shémesh, Tell Batash/Timnah, Khirbet Qeiyafa, Lakish ?Khirbet al-Ra'i), while others from the Philistine plain (Tell es-Safi/Gat, Qubur el-Walayda) and featuring two abecedaries (Izbet Ṣarṭah and Tell Zayit with the reverse order ḥet zayin (instead of zayin ḥet) can be considered “proto-philistian”.

During the 9th century B.C., the shape of letters was increasingly influenced by cursive and began to feature curved tails for certain letters, in particular bet, kaph, mem, noun and pe. A few inscriptions from this period have been found at Abel Bet-Maakah (LBNYW), Tel ‘Amal (LNMŠ, ca. 900), Tell el-Ḥamme (L'Ḥ'B), Tell Rehov (strata V-IV: LNMŠ, LNMŠ, LŠQY NMŠ, ’LṢDQ ŠḤLY, M'NR'M, L'LYŠ‘, B), Es-Semu‘/Eshtemoa (ḤMŠ), ‘Arad (ostracon 76 and possibly 80).

The 8th century B.C. seems to be marked by the spread of writing in both Israel and Judah. The first half of the 8th century in Israel was characterized by significant political and economic development under the kings Joash (c. 805-803-790) and Jeroboam II (c. 790-750), during whose reigns were found some 100 Hebrew ostraca in Samaria, as well as the numerous Hebrew and Phoenician inscriptions at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud, guarding the caravan route between the Red Sea and Gaza. This is also the period of a number of inscribed seals, in particular that of “Shema‘ servant/minister of Jeroboam (II)”. The inscriptions of Kuntillet ‘Ajrud also bear witness to the way in which people learned to write (isolated letters, alphabets, blessing formulas at the beginning of messages, lists of proper names, learning of hieratic numerals, drawings...). This development continued in the third quarter of the 8th century until the fall of Samaria (722 B.C.) with ostraca (Tel Dan, Samaria, Ḥazor, Beth-Shean, Gezer), a small fragment of a stele (Samaria), seals (such as that of a minister of’Hosée, the last king of Israel) and jars stamped with a proper name (WSS nos. 669, 671, 692).

Image opposite: from left to right:

- Seal of a servant (minister) of the king of Israel, Hoshea. H: 24.6 mm; W: 18.2 mm; D: 8.8 mm.

- Impression: «to Abdi, servant of Hoshea».»

Abdi, common form of Abdiyo with the theophoric element YO. The name is also found in Hebrew as Obadias or Obadyahu, servant of YHWH.

- Drawing: Egyptian-style man. He holds a lotus-shaped scepter in his left hand.

At his feet, a winged sun, another Egyptian figure. André Lemaire.

In the center, a walking man gestures with his right hand, while with his left he holds out a sort of lotus-blossom scepter; he wears a wig. His carriage and skirt are Egyptian in style, which was common at the time, even in Israel. Under his feet is a winged sun, another Egyptian motif. The owner's identification is in Paleo-Hebrew, typical of the second half of the 8th century (750-700 BC).

These “Israelite” inscriptions reveal that the Hebrew of the kingdom of Israel was different from Judean Hebrew (and Biblical Hebrew) and close to Phoenician, with the resolution of diphthongs (YN instead of YYN) and certain assimilations of the nun (ŠT instead of ŠNH).

Judean Hebrew inscriptions also become more numerous in the 8th century BC, although paradoxically two seals (WSS no. 3-4) of servants/ministers of Judah's king ‘Uzyahu (ca. 790-776-739) adopt the “Israelite” spelling (‘ZYW), whereas his successors, Jotam (ca. 739-735/4), Ahaz (ca. 735/4- 719), Ḥizqiyahu/Hezekiah (circa 727-719-699) are known indirectly from a seal (WSS no. 5) and directly from several bullae.

Image opposite: the seal with its three registers. © Eilat Mazar, photography by Ouria Tadmor.

A number of inscriptions found in tombs around Khirbet el-Kawm/Maqqédah date from approximately the middle of the 8th century BC. or incised on vases, as well as an inscription on an ivory grenade.

In the second half of the 8th century, in addition to seals and bullae, more than 2,000 royal stamps on jar handles are known (LMLK = belonging to the king) and hundreds of proper name stamps.

Image opposite: the Hezekiah Tunnel inscription now on display at the Museum of the Ancient Orient in Istanbul, Turkey. Montage © Théo Truschel.

Image opposite: the Hezekiah Tunnel inscription now on display at the Museum of the Ancient Orient in Istanbul, Turkey. Montage © Théo Truschel.

In addition to the ostraca from Arad (especially nos. 49-57) and Lakish, and the graffiti from El-Jib and Khirbet Beit Lei dating from this period, we should also mention the famous Siloam Canal inscription in the tunnel of Hezekiah, discovered in the 19th century, several funerary inscriptions from the village of Silwan near Jerusalem and several engraved or ink inscriptions discovered in Jerusalem.

Find out more

Under the direction of Rina Viers, founding president of Alphabets, the association has just published a major work:

Mediterranean alphabets, Peoples and languages

The main alphabets of the Mediterranean peoples are represented.

This book brings together 14 scientists in their respective disciplines: Pascal VERNUS (Égypsum), Dominique BRIQUEL (Greek, Etruscan and Latin), Françoise BRIQUEL-CHATONNET (Syriac), André LEMAIRE (Canaanite, Aramaic, Phoenician and Paleo-Hebrew), and others.

Éditions Alphabets, Nice, 2025.

Image opposite: the Hezekiah Tunnel inscription now on display at the Museum of the Ancient Orient in Istanbul, Turkey. Montage © Théo Truschel.

Image opposite: the Hezekiah Tunnel inscription now on display at the Museum of the Ancient Orient in Istanbul, Turkey. Montage © Théo Truschel.