Bible, History, Archaeology

History,

Archaeology

Home >

Herod I the Great, King of Judea

The Judean king Herod, contemporary of such famous men as Julius Caesar, Mark Antony, Cleopatra and Octavian Augustus, left his mark on the history of his country, Judea, and beyond to the Mediterranean East. Flavius Josephus, and to a certain extent the New Testament, are no strangers to his tumultuous fame.

Introduction,

Introduction,

the sources

Our historical knowledge of Herod the Great (37 to 4 B.C.) depends almost entirely on what the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus on the subject (Jewish antiques, books XIV to XVII and the Jewish War, book I). It takes up, sometimes explicitly, entire passages from the now defunct work of Nicholas of Damascus, official historian to the court of Herod the Great. Even if Flavius Josephus corrects here and there some passages that are clearly of complacency, he seems to have drawn faithfully on the discourse of the historian contemporary with the events, sometimes supplemented by additions or complements from other ancient authors such as Strabo.

Image opposite: Jewish coinage (AE prutah) bearing the effigy of Herod I the Great.

Obverse, D/ HPW BACIΛ. reverse, R, with double cornucopia with caduceus. Minted in Jerusalem. Hendin 1188. Marc Truschel Private Collection.

However, despite the staging, Herod is portrayed in an extremely dark light.. The discourse is damning on the man's violence, even if on several occasions, the text tries to rehabilitate him by describing his punctual aid to the kingdom's famine-stricken populations, or his glorious eggetic policy, in particular with the reconstruction of the Jerusalem Temple.

Rome's role in the emergence of the Herodian family in Judea

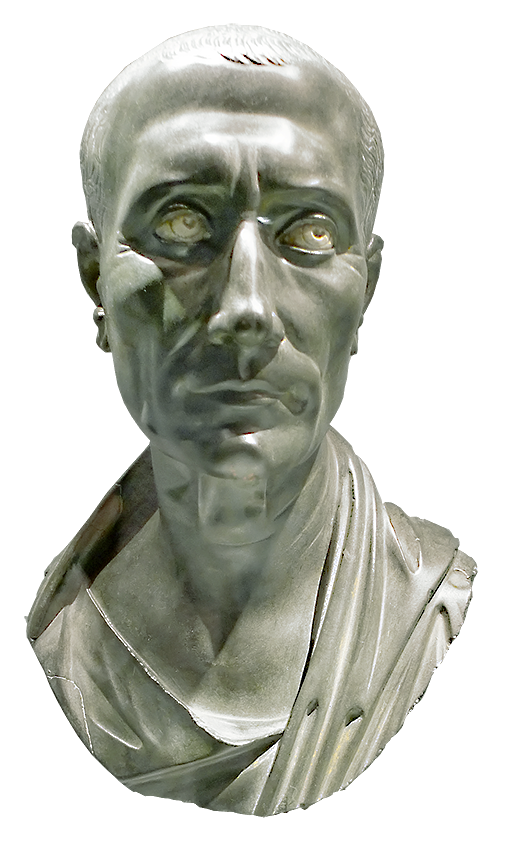

Image opposite: bust of Gaius Julius Caesar, basalt. Mid 1st century B.C. Berlin Museum © Théo Truschel.

The major geopolitical change in the entire region came with Pompey's arrival in the East in the 60s. In 63BC, when Pompey arrived in Damascus as a conqueror, he was called in as arbiter by Hyrcan II and Antigonus, the two Jewish brothers, who were vying for power further south in the remnants of the Hasmonean empire. The rise of Herod's family was based on this rivalry between the two branches of the Hasmonean family. Let's take a closer look. Pompey himself intervened in the family conflict. He took Jerusalem and all Hasmonaean territory fell into his hands. Of the two pretenders to the throne, he chose the elder brother, Hyrcan II, and appointed him high priest in Jerusalem, but stripped him of the royal title. The territory was severely amputated and administratively reorganized by Gabinius, the new Roman governor of the whole region including Syria.

According to the tradition preserved in the works of Flavius Josephus, the new strongman of the time, who worked in the shadow of Hyrcanus II, was Antipater. Father of Herod the Great, he was wealthy and possessed an extensive regional network of influence. During the internal struggles that shook Rome and its Empire, between Pompey and Caesar, then Antony and Octavian Augustus, Antipater's family and its vast eastern network soon proved to be an indispensable auxiliary to the Roman pretenders for the stability of the region. Antipater's family came from Idumea, a region south of Judea, which had just emerged from paganism to be Judaized by the Hasmoneans. Antipater had married Cypros, an Arab princess from the neighboring Nabataean kingdom. He was therefore closely linked to the royal family of Petra. At the time, it was a wealthy town, controlling the caravan trade from the mythical lands to the south.

An illustration of a possible reconstruction of the city of Jerusalem at the time of King Herod I the Great. The Temple erected by Herod can be seen on the right © DR.

Herod, a kingdom to conquer

Image opposite: gold coin, aureus, of Octavian Augustus, minted in Lyon in 10 B.C. © Bibliothèque en ligne Gallica.

Herod was already familiar with the experience of power, having been put in charge of Galilee under Julius Caesar, his father's political representative in Judea. Flavius Josephus reports that he quickly put an end to the brigandage endemic in the region, earning him the gratitude of the inhabitants. But by 40BC, it was a different matter... It took him almost three years to take possession of his kingdom, with the help - albeit belated - of two Roman legions. In the spring of 37 BC, Jerusalem fell to Herod's armies. The old Hasmonean dynasty, which had been born in the bloody struggle between Judea and the Seleucids 130 years earlier, suddenly disappeared from the political scene with the defeat of Antigonus and his party, and his death a few months later.

A new page was opened, that of a Judea entrusted to Herod by the masters of Rome. As for the new power's quest for legitimacy in the eyes of the Jewish people, this was to be achieved through a family alliance with the other Hasmonean branch, that of Hyrcan II. In the midst of the siege of Jerusalem, Herod decided to marry Mariamne, granddaughter of Hyrcan II. She was to bear him children, but would end up murdered like most of her family.

Herod, the king

Image opposite: rare gold coin, aureus, Mark Antony and Octavian in 41, minted to celebrate the second triumvirate.

From left to right: M ANT IMP AVG III VIR R P C M BARBAT Q P. Bare head on Marc Antony's right.

CAESAR IMP PONT III VIR R P C. Naked head on Octavian's right. © cngcoins.com

Herod, who almost lost his life several times during his long life, fought relentlessly against all these threats. They made him sick with suspicion. Reading the texts, which are extraordinarily detailed for the life of a ruler in those days, King Herod was clearly a case for psychiatry. Moreover, to reinforce the dark side of the character, Flavius Josephus insisted that he held on to power only at the cost of repeated renunciations and murders, which first struck his own family. He spent his life building up his kingship to the detriment of all other considerations. Other characters, such as Hyrcan II, are presented in this mad, macabre mise-en-scène as paragons of modesty and dignity. Quite the opposite of Herod the Great's conduct.

From Jerusalem to Actium (37 to 30 BC),

the beginnings of royalty

The forces at work in the region under the eastern reign of Cleopatra's lover Mark Antony posed real threats to the fragile foundations of the new Jewish kingship. Within the kingdom, Herod had to contend with the claims of his mother-in-law, supported by Cleopatra, but there was far greater pressure on the kingdom's borders. The beautiful and famous Egyptian queen Cleopatra herself coveted the riches and strategic position of the Jewish kingdom. And although Herod's relations with Mark Antony were very skilful, he had to cede some of his territory to the queen's insatiable appetites. This mainly concerned the region of Jericho and Ein-Gedi, famous throughout the East for its production of rare essences. In addition, Herod found himself engaged, at the behest of the Roman triumvir, in a war with the Nabataean Arabs, which almost cost him his life. He found himself in great difficulty at the start of hostilities in 32-31 BC. This war took place precisely during the final phase of the merciless struggle between Mark Antony and Octavian. As a result, he did not have to fight alongside Mark Antony against Octavian. In a way, the circumstances that kept him away from this front saved his future as king. At Actium 30 BC, Octavian won a crushing victory over Mark Antony, who fled to Egypt to die. Herod, to whom Mark Antony had entrusted responsibility for the territories taken by Cleopatra from the Nabataeans, had fulfilled his mission with difficulty, defeating Malchus, King of Petra. But his protector, Mark Antony, was no more. Worse still, his name had become a threat to the continuity of Herod's reign. A way had to be found to rally to Octavian Augustus. The geopolitics of the region suddenly shifted with the consequences of this battle.

Herod, Octavian Augustus' ally

Image opposite: Statue of Octavian Augustus. First Roman emperor. Musée du Louvre. Théo Truschel.

As a result, Herod was considered one of the most important monarchs in the East, and foreign authors called him the “Great”. Rome had entrusted him with full authority over the kingdom's internal affairs, i.e. administrative, judicial and financial affairs, as well as the management of his own army. To this end, he set up new Hellenistic-influenced institutions and continued to contain and limit the role of the Sanhedrin. In the manner of Hellenistic princes, he surrounded himself with a Court of “the king's friends”, which included the Prince's Council. In this way, Herod abandoned the Jewish tradition in favor of the Greek model of thought and society, which was dominant in the region. This is one of the themes of the presentation of Herod's reign. In the same vein, power was not to leave the new royal family. Octavian had granted him the privilege of naming his successor, with validation of the choice by Rome. The Herodian dynasty would rule Judea through the will of the Roman emperors for three generations.

Herod and his family, a tragedy

At precisely the time when Rome was recognizing the legitimacy of Herod's power over the region by removing the Egyptian threat, the Judean king was experiencing immense domestic hardship. These family troubles culminated in the murder of Hyrcan II and then of his wife Mariamne, suspected of having cheated on him. With almost theatrical effect, the blind and sickly jealousy of the King of Judea was made all the more abject by his wife's extremely dignified attitude in the face of his death sentence and all manner of slander and betrayal - even from her own mother. The staging is terrifying, and later inspired classical theater with its tragic quality. The texts show that Herod's death was an event he deeply regretted, and one that seemed to haunt him to the point of illness.

Image opposite:

Image opposite:

Copper coin (prutah) bearing the effigy of Herod I, minted in Jerusalem around 37-34 BC.

Obverse

Description: theegende around an anchor.

Obverse legend: HROD BASIL.obverse translation: (Herod king).

Revers

Reverse titling: ANÉPIGRAPHE.

Description: two horns of plenty with a caduceus (attribute of the Greek mythological god Hermes) in the middle.

Courtesy of Marc Truschel.

This tragic episode in Herod's tumultuous life, followed by the murder of Mariamne's mother and then her brother-in-law, the strongman of the moment in Idumaea, opens up a new chapter in the king's history. Indeed, the serial murders, within months of each other, of Hyrcan II, his wife, his mother-in-law and his brother-in-law led to the disappearance of all male offspring from the various Hasmonean branches. Fear of conspiracy seems to have been the primary cause of these assassinations. But it is also intrinsically linked to the fear of an internal challenge to the legitimacy of his power. Through all his actions, the texts make him question his origin and identity. In the end, he was merely Rome's successful candidate in the region. However, the kingdom's elites - or so the texts show - don't seem to have recognized him as such, preferring - by far - the Hasmonean descendants.

Herod was married to ten women, eight of whom are mentioned. From these unions he had fifteen sons and daughters. The size of the family was not conducive to the establishment of a serene climate. Flavius Josephus draws the reader's attention to two of his sons. They were those he had with Mariamne, of royal descent, who as soon as they returned from Rome, where they had been educated, challenged their father's power by accusing him of the murder of their innocent mother. They ended up before a court that condemned them to death. This led Octavian Augustus to say that it was better to be Herod's pig than his son! What an image!

The end of the reign was made chaotic by the struggle between all the pretenders to the throne. Herod even had several wills made. When he died in 4BC, he left power to Archelaus, Herod Antipas and Philip, three of his grandchildren. But Octavian Augustus, who had the power to overturn the deceased king's last wishes, recognized only Archelaus as ethnarch and Herod Antipas and Philip as tetrarchs. The story of Rome's dismantling of the kingdom had only just begun. Herod failed to prepare his succession, fearing a coup d'état from within his own family.

Herod nevertheless left a well-administered kingdom, forged by an iron fist. It was a police state which, while continuing to purge certain hostile circles, managed to bring taxes into the treasury. Herod was able to seize the property of all his enemies, increasing his personal fortune immeasurably, and in so doing, he was able to buy himself a place as king from Rome several times over. The kingdom was also architecturally remodeled, with new towns founded and typical Greco-Roman buildings erected. Herod left his mark on the landscape of the entire region and beyond with an eggetic policy that took him as far afield as Greece.

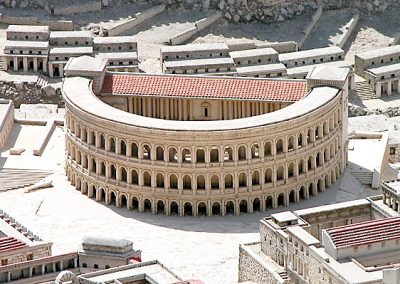

Reconstruction of the Temple of Jerusalem, in the Israel Museum, erected by Herod the Great. © Berthold Werner.

Reconstruction of the Temple of Jerusalem, erected by Herod the Great, at the Israel Museum.

Reconstruction of the Jerusalem theater, in the Israel Museum, erected by Herod the Great. © Berthold Werner.

Reconstruction of the Jerusalem theater, in the Israel Museum, built by Herod the Great.

Detail of the model of the Antonia fortress, which stood next to the Temple and served as a watchtower. © Berthold Werner.

Detail of the model of the Antonia fortress, which stood next to the Temple and served as a watchtower. the Temple.

Reconstruction of the Jerusalem racecourse built by Herod. 1:50 scale model currently on display at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. Berthold Werner.

Reconstruction of the Jerusalem racecourse built by Herod. 1:50 scale model currently on display Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

Caesarea aqueduct built by Herod the Great. © Theo Truschel.

The Caesarea aqueduct built by Herod the Great.

Introduction,

Introduction,

Image opposite:

Image opposite: