Bible, History, Archaeology

History,

Archaeology

Home >

Darius I,

«The Great King»

A tireless fighter of uncommon intelligence and energy, Darius I reigned from 522 to 486 B.C. He appears in history as the successor to Cyrus II the Great, continuing his work of conquest and integration of numerous regions into the Empire, as well as a policy of monumental construction that archaeology still bears witness to today.

Who is Darius I?

Image opposite: a representation of Darius I on one of the columns in Persepolis. Gilles Rheims.

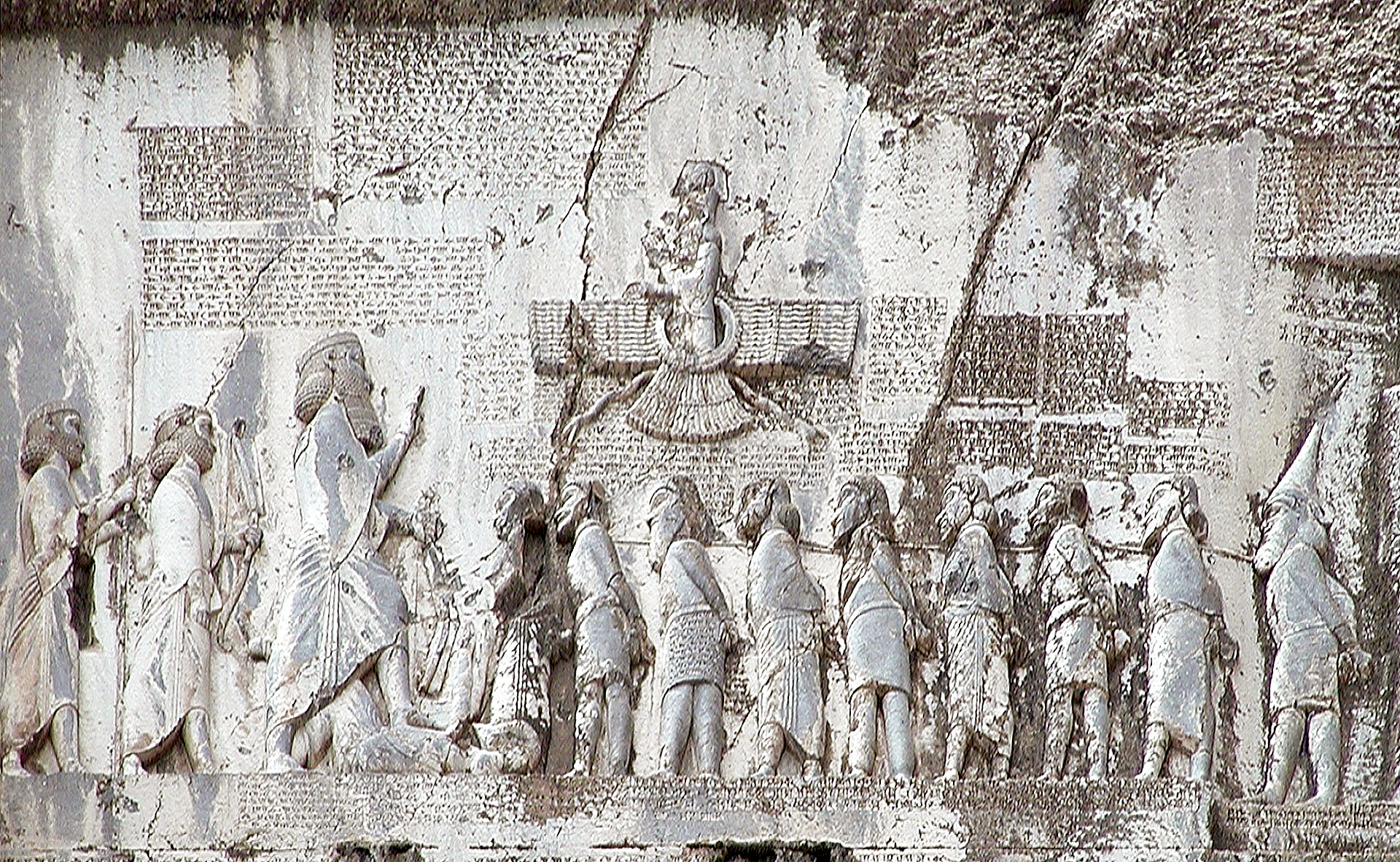

The Behistoun inscription celebrates the crushing of the revolts that marked the beginning of Darius I's reign..

The large relief stands 80 m above the plain. Engraved on a polished surface measuring 3 m by 5.5 m, it shows Darius I, taller than all the other figures, dressed in Persian robes, his head crowned with a diadem. In his left hand, he holds a bow (the bow and spear being the symbol of Persian power). His right hand is raised to face level. Above his head is his title. In front of him, bound together by a rope around the neck, hands tied behind the back, are nine «lying kings», distinguished by inscriptions naming them. Gaumata (the magician) lies on his back, pleading with the king who dominates him. Public domain.

Coming to power

In 522, shortly before the death of Cambyses, who was campaigning in Egypt, a usurper seized the throne in Persia. Herodotus called him Smerdis (or Bardiya), Darius Gaumata. Darius denounced him as a magician who had eliminated Smerdis, Cambyses« younger brother, by taking advantage of a physical resemblance. Historians are still puzzling over this character, despite Darius» assertions that he was concerned with dynastic legitimization. Indeed, during the "plot of the seven" (Darius and six conspirators) Gaumata was assassinated and Darius became king.

As soon as he took power, Darius and his generals encountered a number of rebellions throughout the Empire. Darius himself lists the countries that revolted: Persia, Elam, Assyria, Media, Egypt, Parthia... Four of the six conspirators of 622 are listed among his generals, as is his father Hystaspes; it seems that the rebels, isolated from each other and without a common plan, were quickly defeated; Darius boasts of 19 victories: «I swear by Ahura-Mazda that I have done this truly ... in one and the same year». This is what he declares on the Behistoun rock, which is the only account we have of the events. Engraved in three versions: Elamite, Babylonian and Old Persian, these monumental inscriptions are of great importance, for the Persians, like the Medes before them, favored oral tradition, and we have very few written documents.

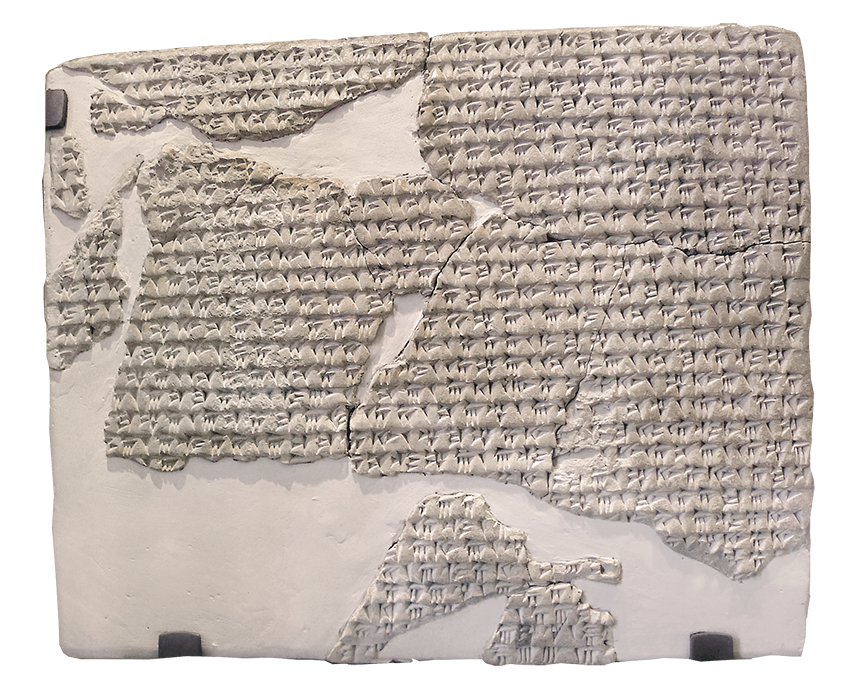

Image opposite: a foundation charter for the palace of Darius I in Old Persian. Theo Truschel.

Engraved on a polished surface measuring 3 m by 5.5 m, it shows Darius I, taller than all the other figures, dressed in Persian robes, his head crowned with a diadem. In his left hand, he holds a bow (the bow and spear being the symbol of Persian power). His right hand is raised to face level. Above his head is his title.

In front of him, bound together by a rope around the neck, hands tied behind the back, are nine «lying kings», distinguished by inscriptions naming them. Gaumata (the magician) lies on his back, pleading with the king who dominates him. The last king was defeated and added to the monument two years later: the king of the Saka of Central Asia, recognizable by his high, arrow-headed cap.

Defeated kings are called «liars» because they have «lied to the people» by leading them into revolt; disloyalty and revolt are lies opposed by truth, i.e. loyalty to power, Darius being an example of truth; these terms, which he uses frequently, have a political as well as a religious connotation. Last but not least, it is believed to represent Ahura-Mazda, the great Persian god, whose power and protection gave Darius victory and the kingdom. Emerging from a winged disc above the scene, a bearded figure dressed in Persian style, wearing a cylindrical headdress surmounted by a six-pointed star, holds a ring in his left hand which he appears to be holding out to Darius, who, for his part, appears to be raising his hand as if to take the ring. This is an investiture scene: Darius I is Ahura-Mazda's lieutenant, and this privileged alliance confers absolute power on the king. This propaganda text is engraved in three languages: Old Persian, Elamite and Babylonian.

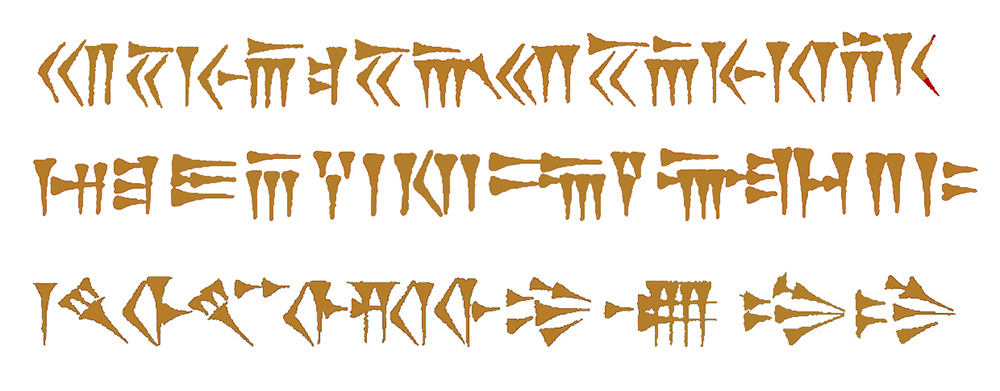

Image opposite: the three scripts in use at the time of the Achaemenid Empire. From top to bottom: Old Persian, Elamite and Babylonian. © Théo Truschel.

Image opposite: the three scripts in use at the time of the Achaemenid Empire. From top to bottom: Old Persian, Elamite and Babylonian. © Théo Truschel.

To view the page of the three cuneiform inscriptions of Darius I →

Yet, throughout his reign, he had to contend with repeated revolts in his vast Empire. One of the best-known episodes in Western culture is the Ionian revolt, followed by the offensive in Thrace and mainland Greece, halted by the battle of Marathon (first of the Median Wars). Despite this, the Achaemenid Persian Empire was the largest in antiquity (6 million km2); according to a foundation plaque in Persepolis, Darius ruled «from the Sakas beyond Sogdiana, to Kush (Nubia), from the Indus to Sardis», the first example of a «World Empire» in history, bringing together so many regions in a single unitary state.

The great frieze of archers or the “Immortals”

The Achaemenid Persian Empire is represented in the Louvre collections by elements of the sumptuous polychrome decoration of the palace built by Darius I in Susa (circa 525-486 BC). The molded, glazed brick reliefs, which make up this unique ensemble, were brought back by M. Dieulafoy, who discovered them in 1885 and 1886, during his exploration of the palace. © Théo Truschel.

Organization of the Empire

The Persians were exempt from taxation, but the peoples of the Empire owed all taxes, customs, levies and tribute to the Great King, as well as military contingents in the form of soldiers, ships or horses for the cavalry. The subjugated peoples were grouped into vast territorial units (around 25) of an ethnic nature: the satrapies, a term which comes from Old Persian and means «protector of power». Even the most remote regions were thus controlled by the central power. This organization was established under Cyrus II, then reinforced by Darius.

Most satraps were members of the Persian aristocracy, and held their power from the king, to whom they owed their unwavering loyalty. In exchange, they receive gifts, estates and important posts, but never permanently, as the king can withdraw them at any time.

Image opposite: a silver shekel (obverse and reverse) from the Achaemenid Empire. Public domain.

Image opposite: a silver shekel (obverse and reverse) from the Achaemenid Empire. Public domain.

Their advantages were visible: large estates, luxurious palaces and various taxes, including the «satrape's table» tax (of which we have a concrete example in Judah: 40 shekels of silver per day), as well as financial profits from the collection of taxes. They were assisted by numerous officers in charge of the various aspects of administration; they had to maintain order, put down disturbances and revolts, and protect the Empire; their powers were therefore extensive, but they themselves were supervised by men sent regularly by the central power.

Image opposite: a gold daric (obverse and reverse), a common currency during the Achaemenid Empire. Public domain.

Image opposite: a gold daric (obverse and reverse), a common currency during the Achaemenid Empire. Public domain.

The king's orders and his men circulated easily thanks to a dense, well-maintained road network, punctuated by relays, guards and inns providing room and board. Darius even had a canal dug between the Red Sea and the Nile to facilitate communications and trade.

Among Darius's reforms was the introduction of a royal currency, decided during a visit to Sardis (near the gold mines) around 500 BC, consisting of a gold daricle and a silver shekel; this coinage lasted until the end of the Empire..

Religious and cultural aspects

Religious and cultural aspects

Little is known about Persian religion. What we do know is that they offered sacrifices to the forces of nature (sun, fire, water...) in the open air or on the mountains; therefore, there were no temples among them, nor statues of divinities (at least until Artaxerxes II). Darius asserted that his conquests had been made possible by the favor and protection of Ahura-Mazda (or Auramazda), creator of heaven and earth, the Great God, whom he quoted sixty-three times on the rock of Behistoun, putting other gods in the background, without denying their existence and role in official worship. When the king travels, the sacred and eternal Fire, carried on silver altars, leads the procession, followed by the chariot dedicated to Ahura-Mazda.

Image opposite: a well-preserved 2500-year-old Greek bronze Corinthian helmet, probably worn by a soldier during a war with the Persians, has been found in the port of Haifa in Israel. Israel Antiquities Authority (AAI).

Given the extreme diversity of situations, the Persians did not impose their cultural values. Cyrus developed a genuine policy of understanding with the elites of the subjugated countries; he maintained local traditions and religions and took on the local title of sovereign (e.g. Pharaoh in Egypt), fulfilling all his functions. Darius followed the same policy. The Persian language was not imposed either, the language of trade and diplomacy in the Empire being Aramaic.

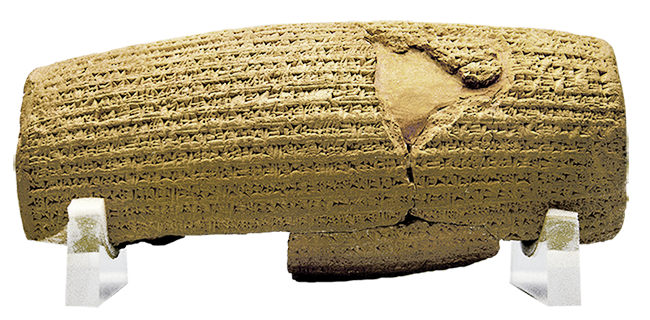

See image opposite: Cyrus II's cylinder authorizing the return of all exiles from the Achaemenid Empire © Théo Truschel.

See image opposite: Cyrus II's cylinder authorizing the return of all exiles from the Achaemenid Empire © Théo Truschel.

A concrete example of religious tolerance is recounted in the Bible, where we see the Judeans, authorized to return to their homeland by Cyrus II the Great, in order to rebuild the Temple of Jerusalem (Books d’Ezra 5; Zechariah 1; Haggai 1; Nehemiah 12, etc.).

After a few years, the governor of Transeuphratene, Tattenai, came on an inspection tour (519/518 B.C.), alerted by the malicious remarks of Judah's neighbors; the elders were unable to provide the edict of Cyrus (539 B.C.), but after research a copy was found in Ecbatane. Darius then allowed work to resume and even made donations in cash and kind, provided the priests «prayed for the life of the king and his sons». On the other hand, in the event of a revolt, the sanctuaries were mercilessly destroyed.

Partial remains of Persepolis today (detail). Persepolis was one of the capitals of the Achaemenid Persian Empire. Erected by Darius I in 521 B.C., the site is located on the Marvdasht plain, at the foot of the Kuh-e Rahmat mountain, around 75 km northeast of the city of Shiraz, Fars province, Iran. Marcin Szymczak 569057026.

Construction

Image opposite: a gold handle with its 3D reconstruction on the missing amphora and the other handle. Théo Truschel.

Gigantic works were carried out, notably to create the immense artificial terraces several meters high, characteristic of Achaemenid residences; tablets found at Persepolis reveal a very high concentration of specialized workers and craftsmen from all over the Empire.

Image opposite: this statue of Darius I was discovered in Susa in 1972. It is one of the few statues in the round featuring a sovereign from the Achaemenid period. It was carved in Egypt and is decorated with hieroglyphs and cuneiform inscriptions in Old Persian, Elamite and Babylonian, specifying that it represents Darius the Great. Behzad39.

Another feature of royal residences is the existence of vast gardens that the Greeks called Paradise. Water management is a constant, as these gardens had to be supplied with water via underground canals that collected rainwater. At Pasargadae, for example, there is an irrigated area of 100 m2, with no ramparts, around a central geometric garden bordered by columned ceremonial buildings. It was in these gardens that the king organized banquets and hunts, the favorite pastimes of the Persian nobility.

Darius had a rock tomb built at Naqsh-i Rustam, four kilometers north of Persepolis, his capital. The decoration carved into the rock reproduces the door and columns of the royal palace. The upper entablature is supported by the representatives of thirty subject peoples, while the king stands on a podium with his bow, the insignia of power, facing an altar of Fire; the representation of Ahura-Mazda overhangs the scene. The king addresses a speech to the spectator «...see these sculptures that bear the throne, there you will know, then you will know that the spear of the Persian man has gone far...»

When Darius died in 486, his younger son Xerxes, already designated by his father, took the throne without encountering any resistance.

The dynastic continuity of the Empire continued until the Macedonian conquest of Alexander the Great. The Achaemenids ruled an immense Empire - the first to be described today as a «world Empire» - and established an original civilization, but apparently failed to win over the subjugated peoples, who showed no support for their sovereign and no resistance to foreign conquest.

Image opposite: the three scripts in use at the time of the Achaemenid Empire. From top to bottom: Old Persian, Elamite and Babylonian. © Théo Truschel.

Image opposite: the three scripts in use at the time of the Achaemenid Empire. From top to bottom: Old Persian, Elamite and Babylonian. © Théo Truschel.

Image opposite: a gold daric (obverse and reverse), a common currency during the Achaemenid Empire. Public domain.

Image opposite: a gold daric (obverse and reverse), a common currency during the Achaemenid Empire. Public domain. Religious and cultural aspects

Religious and cultural aspects