Bible, History, Archaeology

History,

Archaeology

Home > Historical figures > NT figures >

James son of Joseph,

brother of Jesus

Contents:

Introduction - The discovery - A model of Jerusalem in the time of Herod the Great - What is an ossuary? - An image of the Jacques ossuary - Presentation of the Jacques ossuary - The place of discovery - A view of Silwan - Seniority - Registration - Who could be the Jacques of the inscription? - Jacques' death - Probabilities - About the survey - Jerusalem court verdict

Introduction

In 2002, the discovery of an ossuary dating from the middle of the 1st century AD, bearing an inscription in Judeo-Aramaic «James son of Joseph, brother of Jesus», was revealed. The mention of these three names, familiar to readers of the Gospels, has given rise to many passionate comments by researchers around the world, some affirming its authenticity, others denouncing it as a hoax. The unknown location of the burial box has also been the subject of much controversy.

The case was referred to the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) as early as 2003, and complaints were lodged. The Jerusalem court ordered expert reports and handed down its verdict on March 14, 2012.

The discovery

Image opposite: André Lemaire, from the École pratique des Hautes Études (EPHE).

The information was officially announced on Monday October 21, 2002, at a press conference in Washington organized by the Biblical Archaeology Review (BAR) and Discovery Channel. It received extensive media coverage, as the discovery represents an event in the field of New Testament biblical-historical studies.

At the annual meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature (SBL) in Toronto, Canada, on November 23-24, 2002, several specialists discussed this discovery with Professor A. Lemaire of the École pratique Hautes Études (EPHE). Lemaire of the École Pratique des Hautes Études (EPHE).

A general view of the city of Jerusalem at the time of King Herod the Great. Model in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem. Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

What is an ossuary?

Image opposite: one of the many stone «benches» where the body of the deceased was laid, from a tomb in Jerusalem's Valley of the Kings. Image © Todd Bolen.

Immediately after death, the deceased's hands and feet were bandaged and his head covered with a shroud. The whole body was then wrapped in a shroud and perfumed with myrrh and aloes. Sometimes, these aromatics were also placed next to the body in the tomb when burial had been rushed and this method of embalming had not been possible before the funeral. The body, thus prepared, was placed with hands crossed in an open coffin, or rather on a «bench» called a Mitah (which means «bed» in Hebrew).

Émile Puech, epigraphist, director of research at the CNRS and professor at the École Biblique et Archéologique in Jerusalem, explains:

«... It is interesting to note that this usage seems to coincide with the conception of belief in the future life of the Pharisaic School of Shammai (a very important figure in rabbinic literature), as early as the last third of the 1st century BC, [...]. This school of thought advocated preserving the bones of the deceased in an «indestructible» box for the resurrection of the dead, a year or so after the first burial, in a state of maximum purity following purification by decomposition of the flesh in the land of Israel.

The tradition of ossuaries thus spread from the Herodian period towards the end of the 1st century B.C. until the 2nd century A.D., with greater frequency during the 1st century A.D. This could be demonstrated over at least three generations before the fall of Jerusalem and the destruction of its Temple in 70 under the blows of the Roman legions of Titus and Vespasian.

Image opposite: in all probability, this ossuary is that of a member of the Caiaphas family, possibly the high priest in Jerusalem from 15 CE onwards. The name is engraved twice, on the side and on the back. Image © Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

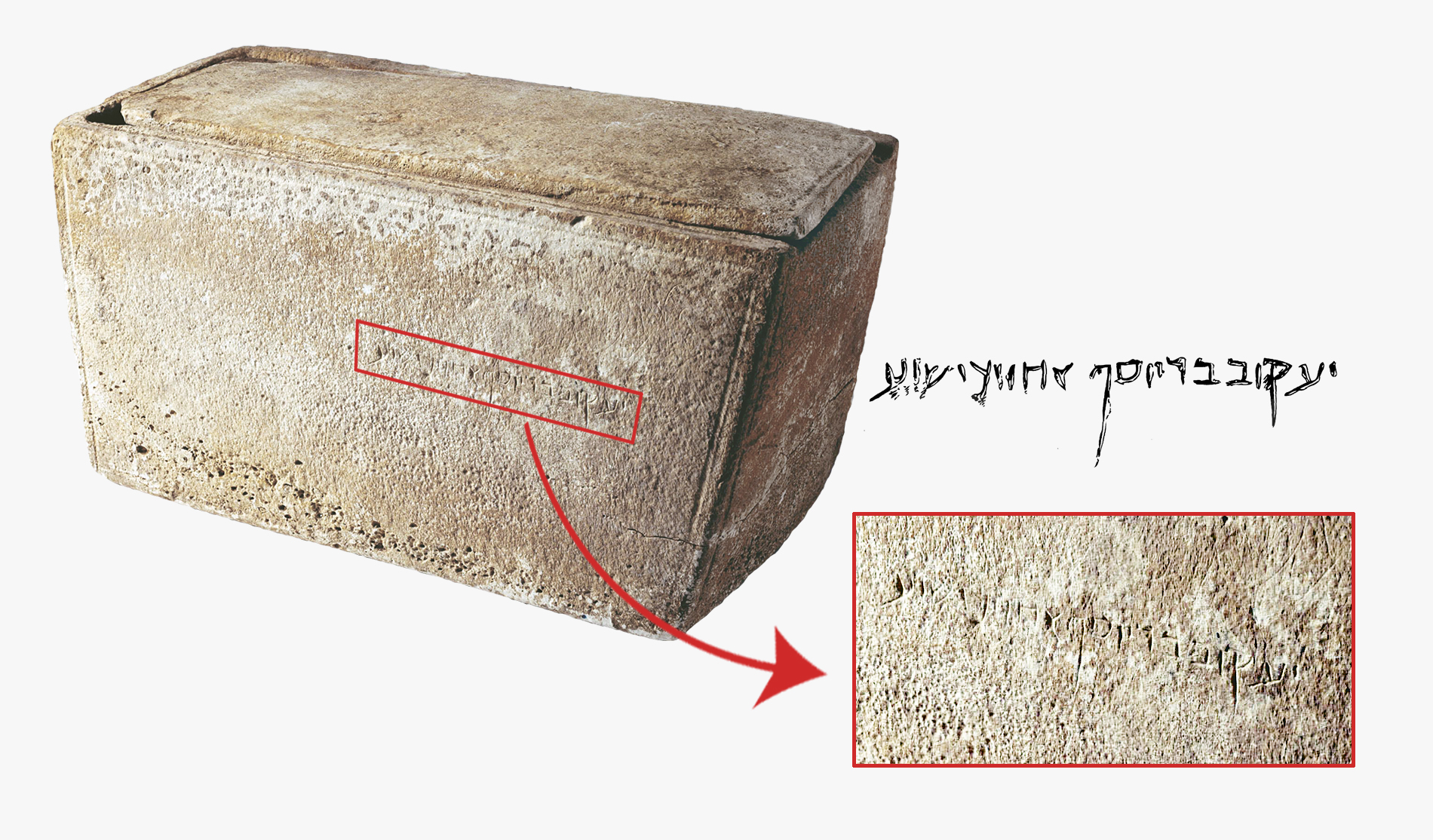

Presentation of the ossuary of James son of Joseph, brother of Jesus, with its inscription. Montage Théo Truschel.

Presentation of the ossuary

This ossuary takes the form of a simple trough-shaped box carved out of a 2.5-centimeter-thick limestone block. The lid is slightly recessed into the box's notched inner edges, by about 0.6 centimeters. The base of the trough measures 50.5 cm, widening to 56 cm at the top, with a height of 30.5 cm and a width of 25 cm. These dimensions are entirely in keeping with the usual dimensions of adult ossuaries, whereas children's or teenagers' ossuaries are generally smaller.

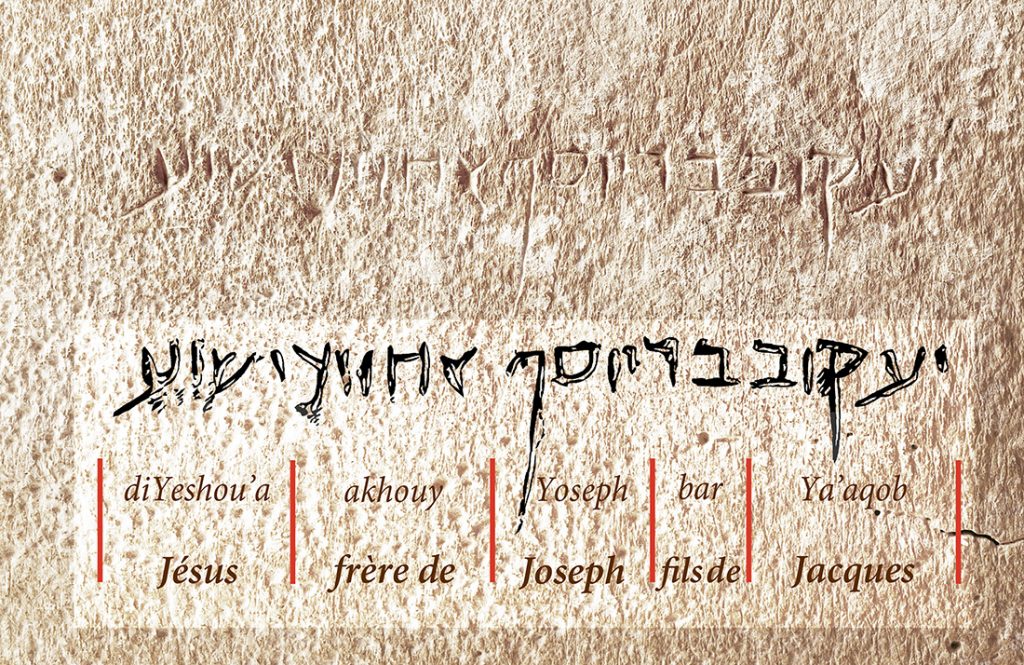

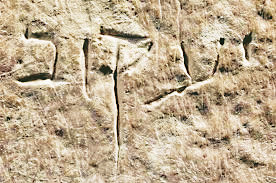

Image opposite: the paleographic inscription from the ossuary of James son of Joseph, brother of Jesus, with its translation. Montage Théo Truschel.

The inscription «James son of Joseph, brother of Jesus» is in classical Judeo-Aramaic script. It consists of twenty letters and is incised on one side. The line is 10.5 centimetres long and, without the stems, the letters are approximately 0.9 centimetres high. There are no spaces between the words. The last letter of the name «Joseph» has the characteristic shape of a pé which indicates that this letter is the last of a word, but not the end of the inscription.

It reads:

Ya'aqob bar Yoseph akhouy diYeshou'a

or «Jacob (or/Jacques) son of Joseph, brother of Jesus».

(James or Jacob are the two possible translations of the same Hebrew or Aramaic name).

This inscription poses no reading problems.

The place of discovery

Unfortunately, the crate did not come from an official excavation, having been purchased by the Israeli collector from a Jerusalem antique dealer, who in turn had acquired it from illegal diggers. The precise location of its discovery is therefore unknown: it is thought to have been unearthed in Jerusalem in the Silwan district, south-east of the City of David. This is consistent with the mineral composition of the limestone in the ossuary itself, as well as with the soil residues attached to the outer part of its base, analyzed in the laboratory by the Israel Geological Survey.

A number of specialists deplored the ossuary's uncertain, and therefore questionable, origin, and are generally reluctant to comment on remains from unofficial excavations.

The most significant counter-example, however, is the Dead Sea Scrolls. Placed on the antiquities market in fragments, even though their place of origin was unknown, they were eventually recognized as authentic, and their interest led to official excavations in the region. the 11 caves of Qumran (from 1947 to 1956); and even then, it was Bedouins, clandestine diggers, who discovered Cave 4.

A view of Silwan, an East Jerusalem neighborhood located southeast of the City of David, from which it is separated by the Kidron Valley, next to the Old City of Jerusalem. In the background, the Mount of Olives. Moshe EINHORN.

Seniority

The fragile state of the ossuary attests to its age. The Israel Geological Survey subjected the ossuary to several scientific analyses, which determined that the limestone of the funerary case had a patina and that its condition was «consistent with what might be expected» from an object that had been in the soil of Jerusalem for nearly two thousand years (calcium carbonate and various mineral salts); «the stone case would be of the period and would be over nineteen centuries old, showing no trace of modern intervention». The same patina covers the incised letters of the inscription as the rest of the ossuary; if the inscription were recent, this would not be the case.

However, the fact that the box arrived empty of its contents deprives scientists of the possibility of carbon-14 dating the bones of the deceased (as we know, this type of analysis must be carried out on organic material).

Professor Edward J. Keall of the University of Michigan confirmed after further tests that the scientific arguments were in favor of its authenticity. E. J. Keall is also Senior Curator of the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, where the object was exhibited from November 15, 2002 to January 5, 2003. He states: «The studies we have undertaken have convinced us that the ossuary and its inscription are truly ancient and not a modern forgery». Keall maintains that weathering «took place at a uniform rate» and that the inscription «degraded naturally», at the same rate as the adjacent parts of the ossuary».

Orna Cohen, archaeologist, chemist and curator at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, was appointed by the IAA (Israel Antiquities Authority) to analyze the ossuary inscription. She testified to having found ancient natural patina in the incision of the inner and outer engraving of the letters composing the words «brother of Jesus» (het, yod, shin, ayin); no element seems to contradict the antiquity of the inscription, apart from the trace of products that were used to treat the ossuary after its discovery.

In the camp of those who doubt the laboratories' analysis, the names of the following professors should be noted:

In 2006, leading stone patina specialist Dr. Wolfgang E. Krumbein (of Carl von Ossietzky University, Oldenburg, Germany) highlighted the many errors committed in the various analyses carried out by the laboratories: use of inappropriate methodology, erroneous geochemistry, faulty error checking, reliance on unconfirmed data, carelessness in the conduct of operations (such as cleaning and conservation actions), etc.

He was therefore very cautious about the results obtained by the designated laboratories, but defended the authenticity of the patina of the ossuary stone.

Nachum Appelbaum, professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, was more cautious: «The first part of the text may be authentic; the second, on the other hand, is far more dubious. The publication of the Israel Geological Institute's analyses is incomplete and imprecise, and one can imagine anything, starting with fraud, especially as it is perfectly possible to imitate an ancient patina».

Registration

Epigraphists note calligraphic features that are perfectly datable and attest to the age of the inscription. The aleph from akhouy has a form attested in cursive from the middle of the 1st century CE. In addition, the upper line of the dalet descends slightly to the right, a form also attested in 1st-century cursive. Finally, the yod according to this dalet is slightly longer than the other three yods (in Ya'aqob, Yoseph and akhouy) and slightly inclined as it descends to the right, a variant also known in script from the same period.

This mix of monumental and cursive lettering is quite typical of ossuary inscriptions. In fact, these are not monumental inscriptions or copies of manuscripts, but rather graffiti of varying degrees of care, intended to be read only by those entering the family vault for funeral rites.

Image opposite: aerial view of Jerusalem today. The Temple Mount (right), also known as the Esplanade of the Mosques by Muslims, is clearly visible. © Todd Bolen.

Rochelle L. Altmann, an American paleographer, questioned, from an epigraphic point of view, the second part of the inscription, «Brother of Jesus». She concluded that, while the first part of the letters did indeed correspond to the Aramaic alphabet, in square letters, in use in Herodian times, the second part would have been incised in the 3rd or 4th century by a Christian forger. A good forger must be able to perfectly imitate an Aramaic inscription from the 1st century A.D. and, at the same time, avoid errors in Aramaic epigraphy from the same period. According to her, the line of the letters here appears uncertain, the letters badly engraved. Her remarks are interesting, but she is not a specialist in Aramaic epigraphy of this period.

P. Kyle McCarter Jr, linguist and paleographer at Johns Hopkins University, also suggested the possibility that two different hands had engraved the inscription, but he believes it dates back to Antiquity.

Professor A. Lemaire simply replied to these objections: «I think these observations betray a certain lack of practice and experience. The shape of the letters varies constantly, even within an inscription, which surprises us today, as we are used to the standards of printed letters. The style of the letters in the inscription is perfectly in keeping with the period in question».

Peter Richardson, professor at the University of Toronto, agrees with Professor A. Lemaire, confirming that the reference to «Jesus» brother« is authentic. Lemaire, confirming that the phrase »brother of Jesus" is authentic. If this part of the inscription dated from the Byzantine period, or even from the 4th century, it would have read "brother of the Lord", and an allusion to Mary would have had every chance of fitting in with the evolution of Marian doctrine.

Two points are worth noting:

«On the one hand, in the Jerusalem region, this type of ossuary is linked to the stone vase industry that developed during the relatively short period of the so-called «Herodian» era. It is generally placed between around 20 B.C. and 70 A.D. [...].

On the other hand, the paleography of this inscription corresponds to the period of the first two thirds of the 1st century, the cursive form of the aleph, dalet and yod may be a clue in favor of a dating closer to 70 than to the very beginning of our era. However, it is difficult to be definitive on the latter point, and preferable to keep the approximate dating within the first century, before 70...». (André Lemaire).

Who could be the Jacques of the inscription?

There are four different Jameses in the New Testament:

1. First the apostle John's brother; both were sons of Zebedee, a fisherman from Galilee. They were among the first disciples of Jesus of Nazareth. Jesus had nicknamed them «the sons of thunder» (Boanergès) because of their impetuous temperament (Marc 3, 17). This James (later called the Greater), was executed by the sword (c. 41-44; Acts 12, 1-12) by order of King Agrippa I, grandson of Herod the Great.

3. Third, the New Testament mentions James, father of the apostle Jude (Luc 6,16; Acts 1, 13), but we know nothing more about him beyond these two New Testament references.

4. Finally, there's also Jacques who is not part of the «Twelve» (apostles). The Gospels only mention the name Jacques twice (Matthieu 13, 55; Marc 6,3). Paul mentions it in his epistle to the Galatians (Galatians 1, 18-19; 2, 9-12) and refers to him as «the Lord's brother». He is included among «the Lord's brothers», unbelievers during Jesus' lifetime (Jean 7, 5) and who became his disciples after Jesus' resurrection (Acts 1, 14).

Image opposite: bronze pruta bearing the effigy of Agrippa I, grandson of Herod the Great, 41-42 A.D. Obverse: AGRIPA BACILEWC (King Agrippa), Reverse: three barley heads with leaves. Public domain.

The Gospel of Matthieu, in 13:55-56, also presents him as the first-born of the brothers of Jesus of Nazareth: «Is this not the carpenter's son? Is not his mother Mary, and his brothers James, Joseph, Simon and Jude? And aren't all his sisters with us?.

Image opposite: The entrance to a family tomb that probably belonged to Herod's family. On the left of the image, you can clearly see the stone that was rolled to close the tomb © Todd Bolen.

Jacques has been somewhat overshadowed by Christian tradition, because his status as «Jesus» brother« became incompatible with the doctrine of the »perpetual virginity of Mary«, the mother of Jesus. This doctrine asserts that Mary bore only Jesus of Nazareth, and that his »brothers and sisters« were rather »cousins«. James was then considered a half-brother (by Joseph, in the Orthodox tradition that follows the Gospel of James) or a »cousin" of Jesus (in the Catholic tradition). This point of view prevails in Origen (2nd century) and Eusebius (3rd century).

However, as Matthieu in 13:55, there would be no reason to dispute the presentation of the «brothers» of Jesus of Nazareth by the Gospels, as the sons of Joseph and Mary. This is the opinion of Tertullian, Hegesippus (2nd century), and the Protestant community as a whole.

This James, according to biblical tradition, had a great influence on the first Judeo-Christian community and became the head of the Jerusalem Church (Acts 12,17 ; 15,2-29 ; 21,18). He presided over a meeting that came to be known as the «Council of Jerusalem», in which he gave final arbitration by extending the hand of association to the apostle Paul, whose vocation as an evangelist was directed more towards the «Gentiles» of the Greco-Roman world (Acts 15).

As early as around 37 AD, Paul, on his way up to Jerusalem for the first time after his conversion, found it necessary to pay a visit to James, who already held this high position (one of the «pillars» of the Jerusalem church), along with the apostles Peter (Cephas) and John (Galatians 1,19). The importance of James is further underlined in 1 Corinthians 15, 7 by Paul's recognition that «Christ» appeared to James and the other apostles long before he appeared to him.

Tradition has it that the Jews held him in high esteem, calling him James, «The Righteous One» (Eusebius of Caesarea, Ecclesiastical History 2.23), to differentiate it from the other Jacques.

He is probably the author of the first (universal) Catholic epistle that bears his name. For Orthodox Christians, James, «brother of Christ», was one of the seventy disciples sent on mission by Jesus of Nazareth (Luc 10, 1).

Jacques' death

Image opposite: Jacques' name, incised here on the ossuary. Public domain.

According to the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, he died in 62 (Jewish antiques 20, 9, 1) in a period between the death of the Roman procurator of Judea, Porcius Festus (from 59 to 62) and the appointment of his successor Albinus (from 62 to 64).

The date of 62 seems to coincide with the approximate date of the ossuary. «Things would have been clearer if the text of the inscription had referred to James «the Just»," notes A. Lemaire, who has taken a probabilistic approach to the problem. Lemaire, who has approached the problem from a probabilistic point of view.

Probabilities

André Lemaire says: «The press has sometimes presented this inscription as «proof» of the existence of Jesus of Nazareth. This interpretation is not accurate, because identification is a problem of probability and, above all, because the historicity of Jesus is not in doubt for a serious historian who can rely on the convergent literary tradition of the New Testament, Flavius Josephus and classical authors of the 2nd century. The fact remains, however, that it's one thing to know someone through literary tradition, and quite another to see his name engraved in stone some thirty years after his death.»

In fact, apart from written documents, there is little archaeological evidence authenticating the existence of Jesus of Nazareth. To date, the few ancient remains unearthed do not concern Jesus per se, but the historical context of the time: a stele discovered in 1961 in the theater of Caesarea Maritima, bearing the names of Tiberius and Pontius Pilate; the tomb of the high priest Caiaphas unearthed in 1990, etc.

André Lemaire continues: «Even if the names James, Joseph and Jesus were very common at the time, a simple calculation allows us to estimate the number of Judean inhabitants who, in the first century, could be called James, have a father named Joseph and a Jesus for a brother, at around twenty. On the other hand, it was highly unusual to mention the name of a brother on an ossuary after that of the father (there is only one other case of this practice out of some 2,000 to 3,000 recorded ossuaries). There must be a special reason for naming him. It's this interesting coincidence that makes the identification of James and, later, Jesus of Nazareth highly probable. The first names James and Jesus were borne by 10 to 12% of the city's male population. James, on the other hand, is rarer (2 to 3%). Having said that, the attribution of this ossuary to Christ's brother depends on a statistical calculation. That's why I say myself that we don't have absolute certainty».

About the official survey requested by the IAA

Astonishingly and symptomatically, the most renowned experts in the highly restricted field of ancient epigraphy, Israeli Professor Ada Yardeni and Professor André Lemaire, at the center of this case for his analysis, were never summoned to court to give their opinion.

Even if he disputes André Lemaire's hypothesis, Émile Puech nevertheless admits in an interview: «Concerning the authentication of the inscription, I trust Ada Yardeni, the excellent paleographer who transcribed it.»

Ada Yardeni and André Lemaire still maintain the authenticity and age of the inscription. Many other specialists in the same disciplines could have expressed their views, but preferring not to get involved in a debate that seemed to be biased from the outset, they stayed on the sidelines.

Matthew Kalma, magazine editor The Jerusalem Report, who observed all the hearings during the five-year trial, reports the following fact in particular: Dan Bahat, the prosecuting attorney, showed how easy it was for Oded Golan to make counterfeits. Using a small camping gas stove, chalk and a container containing various ingredients (recovered during a search of the defendant's home), he explained how a fake patina could be obtained. The defense, using the same technique, demonstrated that the patina obtained did not adhere to the stone and could be removed effortlessly... which is not the case for the ossuary, etc.

Jerusalem court verdict

On March 14, 2012, after seven years of proceedings in the «counterfeiting trial of the century» with 120 hearings, the summoning of 126 witnesses, over 12.000 pages of testimony, Judge Aharon Farkash of Jerusalem stated in a 475-page verdict the absence of formal proof, the prosecution having failed to demonstrate that the ossuary would have been made and its inscription incised, even partially, at a more recent time and that the pursuit of the various scientific examinations had not proved «... their accusations beyond a reasonable doubt...». He also pointed out that tests carried out in Israel's various forensic laboratories (he was particularly harsh on the Police Forensics Laboratory) had probably «contaminated» the ossuary, making further scientific testing of the inscription impossible in the future...

Image opposite: in 2002, Oded Golan offered for examination the ossuary he owned, the announcement of which caused widespread controversy and led to him being taken to court. DR.

He also noted that this was the first time a criminal court had been called upon to rule on a case involving the counterfeiting of antiques.

He continued: «This does not mean that the inscription on the ossuary is recognized as true and authentic, and that its inscription dates back 2000 years... This subject is likely to continue to be debated and researched in the scientific and archaeological worlds, and time will tell. Furthermore, it has not been formally proven that the «brother of Jesus» part of the inscription refers to Jesus of Nazareth, mentioned in Christian writings».

Collector Oded Golan, who was also accused of adding the second half of the inscription (less deeply incised than the first part, probably due to the difference in hardness of the stone) in an attempt to link it to Jesus of Nazareth, and then fabricating this patina, its bio-organic coating that adheres to ancient objects to pass it off as authentic, was fully acquitted on May 30, 2012, in this case.

His private collection comprises thousands of objects, making it one of the largest private collections in the world and the most important in Israel.

For its part, the Israel Antiquities Authority believes that this case shows the limits of science in demonstrating fraud, and encourages museums and universities worldwide to be more vigilant with regard to antique pieces of uncertain origin.