Bible, History, Archaeology

Bible,

History,

Archaeology

Pontius Pilate,

registration

In 1961, during an archaeological excavation campaign, an Italian mission led by A. Frova of the Lombard Institute of Science and Letters was prospecting the Roman theater at Caesarea Maritime, built by Herod the Great. They unearthed an inscription bearing the name Pontius Pilate. To this day, it remains the only known mention of the man who is ultimately responsible to history for the trial and death of Jesus.

Pontius Pilate

According to tradition, Pontius Pilate was a knight of the equestrian order of the Samnite clan Pontii (hence his Latin name, Pontius Pilatus), i.e. a member of the lesser Roman aristocracy as opposed to the senatorial order.

According to tradition, Pontius Pilate was a knight of the equestrian order of the Samnite clan Pontii (hence his Latin name, Pontius Pilatus), i.e. a member of the lesser Roman aristocracy as opposed to the senatorial order.

Image opposite: bronze pruta (obverse and reverse) used in Judea under Pontius Pilate. With mention of Tiberius. TIBEPIOY KAICAPOC © Hendin 1342.

In 26, the emperor Tiberius appointed him procurator of Judea, or rather prefect, according to an inscription unearthed at Caesarea Maritime. From the outset, Pilate incurred the enmity of the Jews, who criticized him for offending their religious feelings: he was said to have left images of the emperor on display in Jerusalem, and to have minted coins bearing pagan religious symbols. Roman ensigns bearing the emperor's effigy were kept in the Antonia fortress, close to the priestly vestments of the high priest, which was considered sacrilege.

The character of this fifth Roman governor of Judea can only be deduced from later Jewish and Christian accounts, particularly those of Flavius Josephus, Tacitus and Philo of Alexandria. These three sources present him as an authoritarian, violent and clumsy prefect who, although rational and pragmatic, provoked revolt among the Jews and Samaritans.

The New Testament, for its part, portrays Pilate as a weak and indecisive man. Noting that the crowd would rather see Barabbas released than Jesus at Passover (Mark 15:6), Pilate capitulated even though his wife Claudia Procula (her name is mentioned in the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus) had advised him not to take sides (Matthew 27:19).

In 36, the Samaritans denounced Pilate to Lucius Vitellius, legate of Syria, after the severe repression of one of their gatherings on Mount Garizim. Called back to Rome to stand trial for cruelty and oppression, and in particular for executing men without a proper trial, Pontius Pilate was deposed.

The paucity of historical sources has led to the development of legends about him, such as that he was exiled to Vienna (Gaul) or Lucerne (Switzerland) and committed suicide during the reign of Caligula in 39.

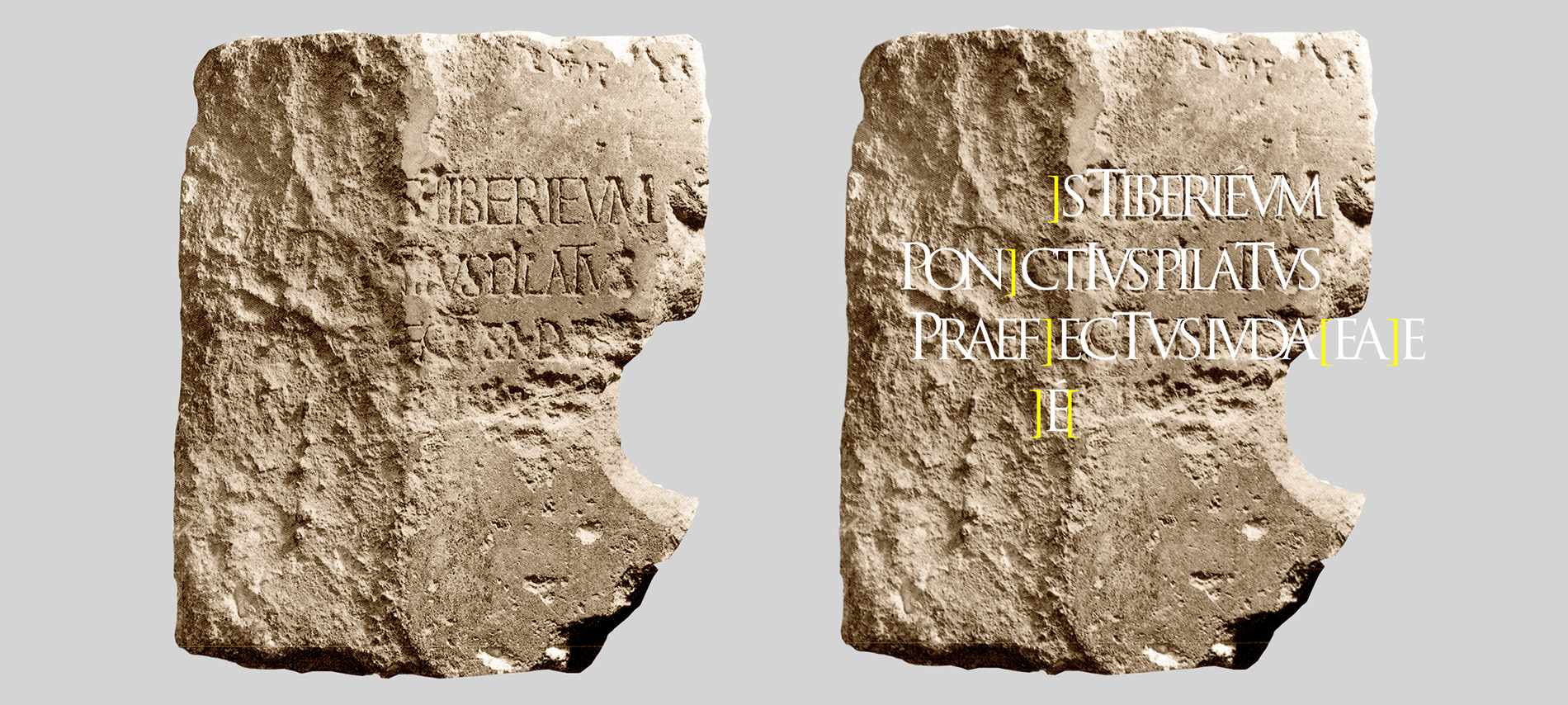

Proposed reconstruction of the Pontius Pilate inscription © Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

«For the inhabitants of Caesarea a Tiberium ... Pontius Pilate ... prefect of Judea ... made».

Historical background

The inscribed stone is relatively small, 82 cm high, 68 cm wide and 21 cm thick. It would have been reused as a staircase step in the Byzantine period (5th-6th century), giving access to the stands from the orchestra. This re-use explains why the left-hand side of the inscription was ground off, to enable the stone to be inserted into the base of the staircase; as a result, there is some uncertainty as to the complete restitution of the inscription.

Proposed reconstruction :

...]STIBERIÉVM

...] PON]TIVS PILATVS

PRAEF]ECTVS IVDA[EA]E

[.......]É[.......]

The text originally consisted of four lines; all that remains of the fourth line is an acute accent. Half of the right-hand side, however, is very well preserved: one can easily read : «...Tiberium...Pontius Pilate...Prefect of Judea...».

The «S» in front of Tiberium may be what remains of a word referring to the inhabitants of Caesarea. But what does Tiberium stand for? Clearly, the name refers to the emperor Tiberius (14-37 A.D.), adopted son and successor of Augustus. The acute accent on the É indicates that this is a monument named after the emperor. But what is the nature of this monument? Those who studied the inscription immediately thought of a temple dedicated to «divine Tiberius».

The very wording of the text rules out such a hypothesis. For it to be a temple, Tiberius would have to be mentioned as the recipient of the monument (in Latin, his name would have to be a dative such as Tiberio), which is not the case here. Only his name is used to define it, just as we use the name of King Mausole d'Halicarnasse to designate a funerary monument: mausoleum. We're more likely to think of it as a civil building that Pontius Pilate had just had built, showing the emperor his respect by naming it after him. The relatively small size of the inscription confirms this interpretation; a dedication inscription identifying a temple dedicated to Tiberius would have to be much larger.

J.-P. Lemonon (author of Pilate et le gouvernement de la Judée, Paris, 1981) suggests that it could be a public square, an administrative building, or even a colonnade, since a portico at Aphrodisias in Asia Minor bore the name Tiberium. The verb expressing Pilate's action in the fourth line must therefore be a FECIT («did»), not a DEDICAVIT («dedicated»), as the vast majority of readers suggest.

Thus, we can translate this mutilated inscription: «For the inhabitants of Caesarea a Tiberium ... Pontius Pilate ... prefect of Judea ... made».

Pontius Pilate's official title

Philo of Alexandria, Tacitus and Flavius Josephus give him the title of procurator (epitropos in Greek), a title retained by all historians; Flavius Josephus and the authors of the New Testament, on the other hand, only give him the title of chef (hêgemôn in Greek), which seems far too vague. Under the emperors Augustus and Tiberius, the title of procurator implied an authority limited to the administration of imperial properties, which certainly did not correspond to the function exercised by Pilate in Judea. The title of præfectus (prefect) which should normally be granted to him. In fact, this title, first attached to a military function in Caesar's time, implied the exercise of administrative power over a province, with civil and criminal jurisdiction. It was only under Claudius (41-54 AD) that the title of procurator also covered the præfectus. Pontius Pilate was a prefect, not a procurator (according to the meaning of this word before Claudius); the three historians mentioned simply used the title customary at the time of their literary activity. As for the New Testament, the term may simply bear witness to the floating of titulature towards the end of Tiberius' reign and before the advent of Claudius, who retained only that of procurator for its administrators of Judean-type provinces.