Bible, History, Archaeology

Bible,

History,

Archaeology

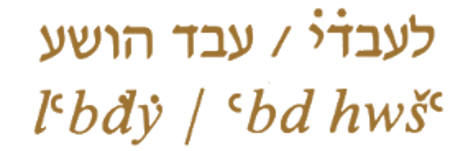

Abdi, servant of Hoshea

(Hosea), last king of Israel

In ancient times, officials authenticated their documents by marking them with a seal on a malleable surface such as fresh clay (bulla). Numerous imprints of Old Testament characters have been unearthed in this way in Israel. Sometimes, the seal itself has been found. Recently, in New York, one of these seals was sold at a high price. It was the seal of a minister of Hosea, the 19th and last king of Israel (732-722 BC).

A seal

The seal impression is a small ball of clay (bubble) glued to strings attaching a roll of papyrus or other document. The marks of the papyrus fibers and strings are still clearly visible on the back of the bulla. The writing is very neat, in the style of the second half of the 8th century BC. Dots (.) separate the words, as on long official and public inscriptions. The owner is certainly an important figure.

Acquisition

In 1993, a wealthy collector in New York acquired a seal with the following text:

«To Abdi, servant of Hoshea»

This text can be read and understood as follows:

«To Abdi» is an abbreviated form for Abdiyo, meaning «Servant of Yahweh», a common name at the time, and «servant (ebed) of Hosea». The word servant, present on other seals, designates a royal minister. The proper name that follows (Hosea) must therefore be that of a king. And didn't Israel's last king bear this name?

Hosea (Hebrew: הושע) was the last king of the northern kingdom, reigning from 732 BC to 722 BC. Not to be confused with his namesake, the prophet Hosea, who also lived in the 8th century BC.

Description of the seal

Description of the seal

The various motifs of the scarab-shaped seal are finely incised in chalcedony.

Image opposite: from left to right:

- Seal of a servant (minister) of the king of Israel, Hoshea. H: 24.6 mm; W: 18.2 mm; D: 8.8 mm.

- Impression: «to Abdi, servant of Hoshea».»

Abdi, common form of Abdiyo with the theophoric element YO. The name is also found in Hebrew as Obadias or Obadyahu, servant of YHWH.

- Drawing: Egyptian-style man. He holds a lotus-shaped scepter in his left hand.

At his feet, a winged sun, another Egyptian figure. André Lemaire.

In the center, a walking man gestures with his right hand, while with his left he holds out a sort of lotus-blossom scepter; he wears a wig. His carriage and skirt are Egyptian in style, which was common at the time, even in Israel. Under his feet is a winged sun, another Egyptian motif. The owner's identification is in Paleo-Hebrew, typical of the second half of the 8th century (750-700 BC).

Historical background

In 732 BC, Hosea conspired against the usurper Peqah, killed him and ascended the throne of the kingdom of Israel (2 Kings 15, 30). The successor to Teglath-Phalasar III, Salmanasar V launched a vast military campaign against the entire region. Hosea was defeated and had to pay tribute. He asked Pharaoh So for help and refused to pay the annual tribute. Egypt does not budge, but Salmanasar invades Israel again in retaliation. Hosea was imprisoned (2 Kings 17:3-4); Samaria, besieged in 725 BC, held out for three years. Salmanasar V probably died the same year (722 BC); Sargon II (722-705 B.C.) succeeded him and took credit for taking the city.

The NeoAssyrians adopted the principle of mass population transplants to wipe out any spirit of resistance. The population of Israel is deported to Khalakh, and on the Khabor, river of Gozan, and to the cities of the Medes (27,290 people according to an inscription by Sargon II and 2 Kings 18:9-12; 17:3). People from Babylon, Kouth, Awa, Hamath and Sefarwaim settled in the cities of Samaria in place of the sons of Israel (2 Kings 17, 24).

The Israelite deportees were scattered in several places, which did not favor a community life and led to their assimilation in these regions of Mesopotamia and lost their identity. They never returned to Israel.

This episode marked the end of the kingdom of Israel (in 721 BC), which became the Assyrian province of Samerina.

Archaeology shows that several Israelite cities in the north were reduced in size or even abandoned, leading to the conclusion that the population had declined sharply. In Judah, on the other hand, population growth was observed at the same time, attributed to the influx of people who had not been deported from the destroyed northern kingdom.

Description of the seal

Description of the seal