Bible, History, Archaeology

History,

Archaeology

Home > Historical figures > Figures of the TA > Egypt >

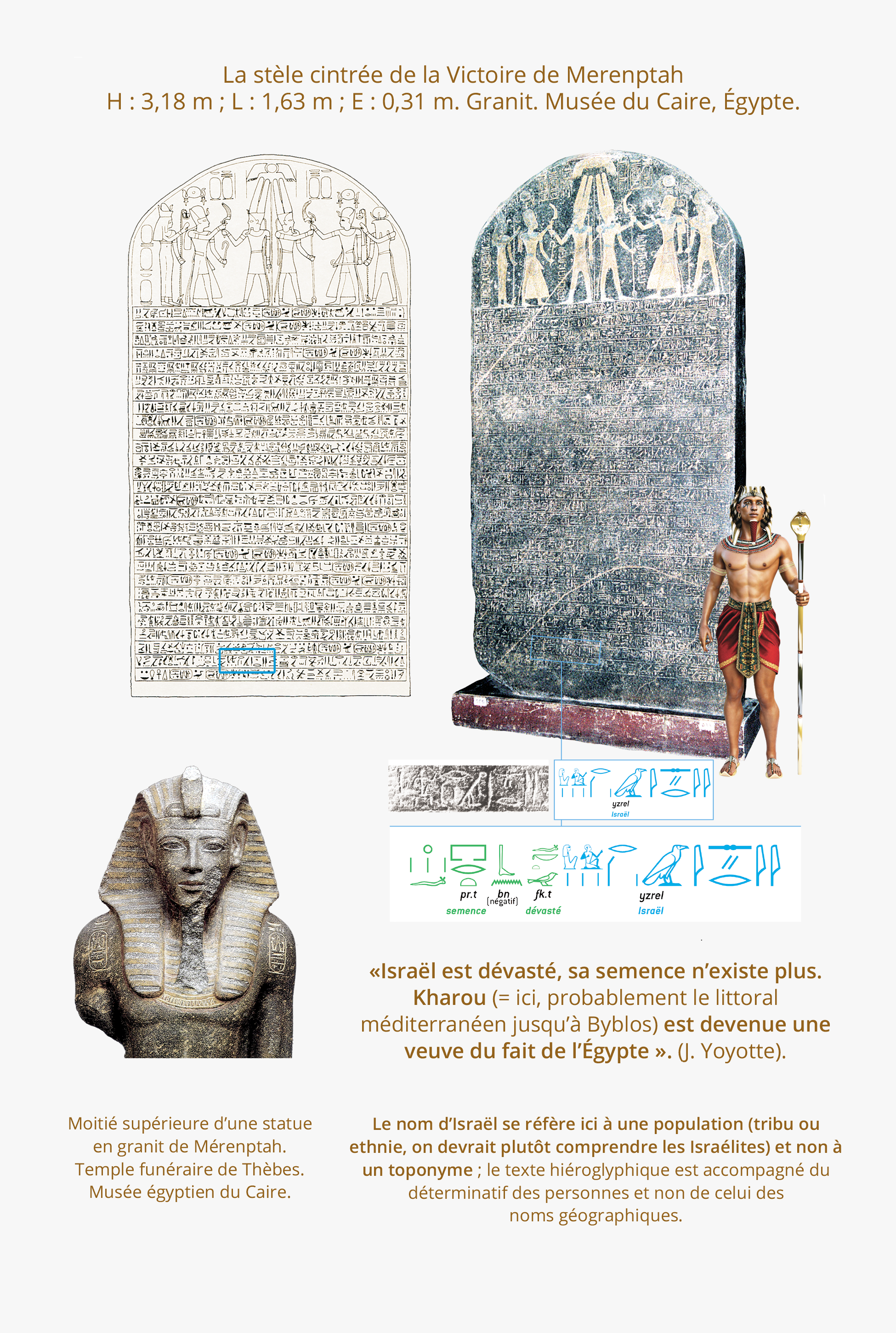

The Merenptah stele

or Israel Stele

Introduction

On closer examination, it appears to have been originally erected by Amenhetep III, probably in his own funerary temple near that of Merenptah. He used the reverse to engrave a hymn to himself on the third day of the third month of Shemu (summer) in year 5 of his reign (circa 1207), to commemorate his victorious military campaign in year 5 against the Libyans and in the land of Canaan.

Image opposite: Sir W. M. Flinders Petrie (1853-1942), one of the fathers of modern archaeology. He was the first to use scientific excavation methods such as stratigraphy, which consists in identifying the successive phases of occupation of a site by means of strata stacked one on top of the other.

The contents of the stele

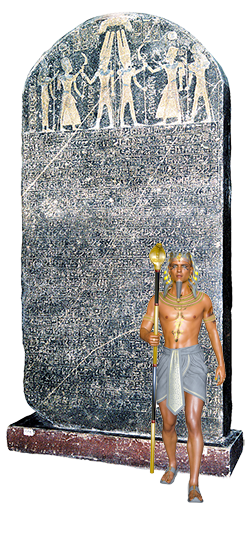

Opposite image: the stele, an imposing grey granite stele 3.18 m high, 1.61 m wide and 31 cm thick..

The Amon-Ra on the right holds in his left hand a sort of long cane, a sceptre ouas, and in his right hand a sword khepech that the king facing him, dressed in a long loincloth and wearing the Khéprech, with his right hand, while with his left he holds a sceptre. heqa. On the left, Amon-Ra, whose left arm grasps the sign ânkh, hands Merenptah a sword Khepech.

The only difference between the two scenes is the object the sovereign holds in his left hand: a scepter. heqa instead of a sceptre ouas.

Beneath the arched section, engraved from right to left, is a 28-line inscription of a long poetic text that first glorifies the power of the sovereign, conqueror of the Tjehenou. Merenptah recalls his ability to protect Memphis and Heliopolis from Libyan invasion, and to restore peace.

Various sources indicate that Merenptah's victory was won over a coalition of Libyans (Libou and Machaouachs) and Sea Peoples (Akaouash, Toursha, Rouk, Shardanes and Shakalash), who were driven out of Egypt. The Sea Peoples returned in years 5 and 8 of Ramesses III (1182-1151), who drove them back in a violent battle in the Delta. This episode is described in a text and images engraved on the outer walls of his temple at Medinet Habou.

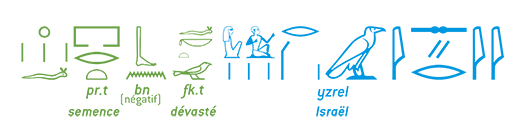

The word Israel on the stele

The stele is particularly famous for containing the only known mention of Israel in Egyptian texts.. The inscription is on the twenty-seventh and penultimate line (see image below), in a list of peoples defeated by Merenptah. It consists of phonetic hieroglyphs that English archaeologist Sir Flinders Petrie interprets as israr and determinative hieroglyphs designating foreign peoples (the man and woman) (the throwing stick). This is not a reference to a state or city, but to a people generally identified with the proto-Israelites.

Image opposite: «Israel is devastated, its seed is no more. Kharou has become a widow because of Egypt». (J. Yoyotte).

The Egyptian army, led by Merenptah, had to follow the coast, cross Gaza and recapture Ascalon and Gézer, strategic points and obligatory passageways to Canaan. These recaptured cities became the base from which the Egyptian army could organize its advance. All these towns, listed in a precise order, were strategic locks preventing access to the coastal plain.

Merenptah, Pharaoh of the Exodus?

Following the absence of Merenptah's body when his tomb and the Royal Cache were discovered at Deir el-Bahari, and the mention of Israel on the stele, many considered at the time that Merenptah was probably the «pharaoh of the Exodus» and his father, Ramses II the Great, the «oppressor pharaoh».

Image opposite: a representation (detail) of a warrior from the «Sea Peoples» engraved on a wall of the temple of Ramses III at Medinet Habou © Théo Truschel.

His mummy was finally found in 1898, when 14 remains from the tomb of Amenophis II (KV 35) in the Valley of the Kings were unearthed. Recent forensic analysis of the remains revealed a strong presence of salt, the result of residual natron used during mummification (H. Sourouzian). Could it be that Pharaoh was drowned with his army when the Egyptians were buried in the waters of the Reed Sea? The Bible does mention Pharaoh's Egyptian army, but not the king himself (Exodus, the Bible, chapter 14), nor his name, which remains the subject of much debate among scholars to this day.

However, it is well established that the Merenptah stele speaks of the eradication of the Israelites already present in the Canaan region, and to hope one day to discover the identity of the two Pharaohs of the Exodus, we would probably have to go back a little further into the past.

The original stele is now on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, while a faithful copy can still be seen at the site of his temple in West Thebes. An important eighty-line inscription on the same subject was carved at Karnak; a column with a similar text, also called the Column of Victory, was found in the ruins of Merenptah's temple at Heliopolis, and other variants were also found on stelae at Memphis, Athribis and Amada...

The Merenptah stele

«Israel is devastated, its seed no longer exists. Kharou (= here, probably the Mediterranean coast as far as Byblos) became a widow because of Egypt».». (J. Yoyotte).

yzrel (group-writing spelling; standard reading: yzyrj3r) fk[[.t]] bn pr.t=f.

«Israel is devastated. [more] of seed/shoot».»

(lit.: «does not exist its seed/growth»).

The name Israel here refers to a population (tribe or ethnic group, we should rather understand Israelites) and not to a toponym; the hieroglyphic text is accompanied by the determinative of persons and not that of geographical names. Pascal Vernus by kind permission.

To view the table, click on the image

«The term pr.t is ambiguous: it can be translated as «seed» in the metaphorical sense of «descendants».

But considering the phraseology of military texts, it is likely that pr.t or to be taken literally as something like «shoot», «plant products», the destruction of an enemy country implies the destruction of its plant resources, whether cereal crops or tree fruits. ». Pascal Vernus by kind permission.

Does the Merenptah stele contain the first mention of Israel?

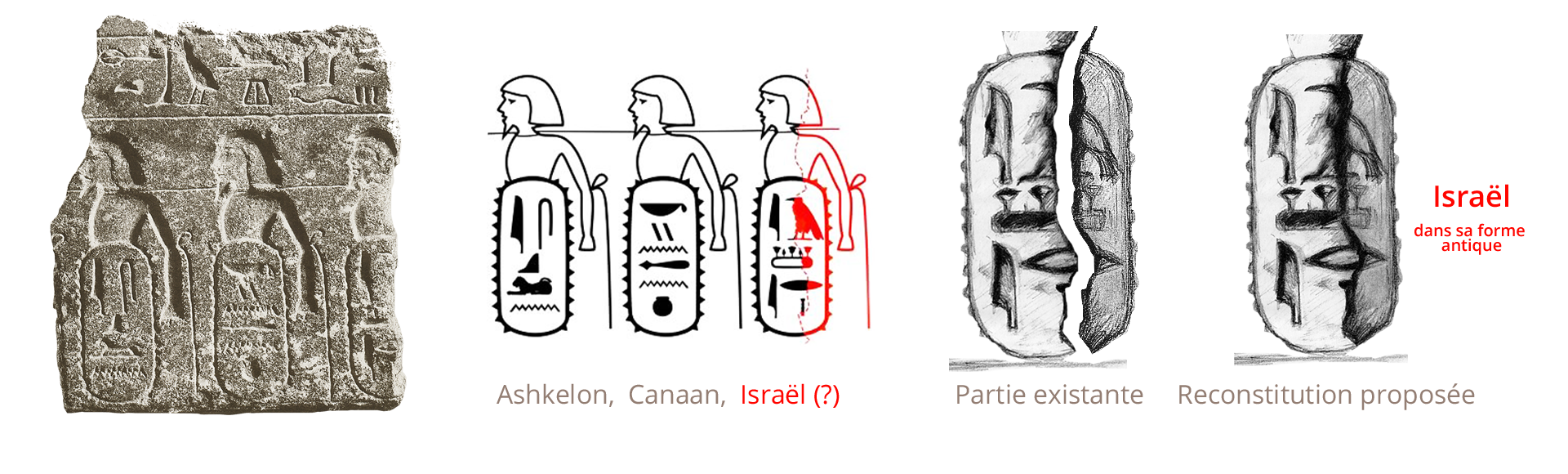

In 1913, German Egyptologist Ludwig Borchardt (1863-1938) acquired a stone statue pedestal from an Egyptian merchant. Three names appear in hieroglyphic characters on this block, which measures between 40 and 45 centimetres: Ashkelon, Canaan and Israel. This last name is identifiable despite a break in the stone. Some researchers and Egyptologists, such as Manfred Görg, Peter van der Veen and Christoffer Theis, believe that this pedestal fragment may predate the Merenptah stele, as the names are spelled differently.

Image opposite: the fragment of a newly rediscovered statue pedestal at the Egyptian Museum in Berlin. Public domain.

To view the pedestal fragment, click on the image.

This newly rediscovered inscription at the Egyptian Museum in Berlin appears to date from around 1400 BC. That's around 200 years older than the Merenptah Stele (1207 BC), considered to be the earliest mention of Israel in Egyptian archaeology.

If the scientists' findings are correct, they would shed new light on the beginnings of ancient Israel.

Image below: the fragment and the restored version of the inscription proposed by scientists Manfred Görg, Peter van der Veen and Christoffer Theis. Drawings by Peter van der Veen/Montage by Théo Truschel.

Find out more

SERVAJEAN Frédéric, Merenptah and the end of the 19th dynasty,

Éditions Pygmalion, Flammarion, Paris, 2014.

Around the age of 60, Merenptah, 13th son of the great Ramses II, succeeded his father as the longest reigning king in ancient Egyptian history. The life of Merenptah is marked by three important documents: a text engraved on a wall of the Karnak temple, a large stele from Athribis in the Delta and the Victory Stele.