Bible, History, Archaeology

Bible,

History,

Archaeology

Cyrus II the Great,

the Achaemenid Empire

Cyrus II the Mede (c. 559-529 BC) was the founder of the immense Persian Empire, or Achaemenid Empire, named after Achaemenes, the eponymous ancestor of the dynasty. He issued a decree of tolerance to free displaced or exiled peoples.

Introduction

Grandson of Astyages, king of the Medes, Cyrus inherited the Persian kingdom, which was then vassal to that of the Medes. Between 553 and 550 B.C., he assembled a large military force that enabled him to defeat his grandfather Astyages and establish himself in his capital, Ecbatane. Then, in the space of a few years, he successively seized the Lydian kingdom of Croesus, the Greek cities of Asia Minor and his most formidable adversary, the Neo-Babylonian kingdom of Nabonides (which then included Mesopotamia, Syria, the Phoenician cities and Judea). He assumed the title of King of the Persians and Medes, inaugurating the largest empire the ancient world had ever known. It stretched from Asia

Image opposite: a bas-relief of Persepolis, one of the capitals of the ancient Achaemenid Empire. Composite image. © Delbars.

In the year of his victory over the Neo-Babylonian Empire, 539 BC, he issued a decree granting freedom to all the exiled and deported peoples of his empire. He thus authorized the Jews of Babylon to return to Judea and build the Second Temple in Jerusalem (Ezra 5,13). To repair the damage caused by Nebuchadnezzar II, he even returned the Temple furniture seized by the latter (Ezra 1,7-11).

Extract from the edict

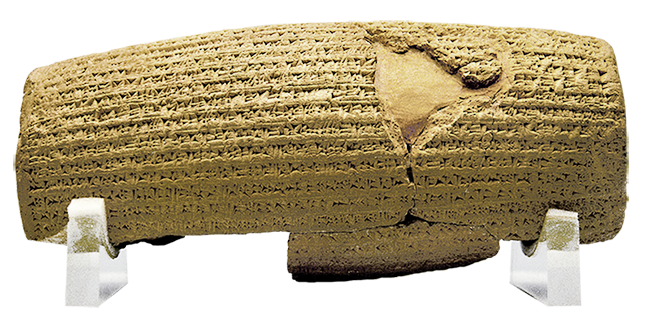

The text of Cyrus' decree was discovered in 1879 in the ruins of ancient Babylon. It appears on a clay cylinder in the form of a long inscription in cuneiform script, now on display at the British Museum in London.

Image opposite: The cylinder of the Edict of Cyrus II, whose Akkadian inscription mentions the possibility of exiles returning to their homelands. © Théo Truschel.

The situation of the Judeans

The situation of the Judeans

The exile of the Hebrews to Babylon had begun after the capture of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar II and the destruction of the Solomon's Temple, around 586 BC. All the city's notables were then sent in exile in Babylon, and the hitherto independent kingdom of Judah became a province of the Neo-Babylonian empire. Later, with the conquest of Cyrus II, Judah formed the province Yehoud Medinata, or simply Yehoud (origin of the word Jew).

Cyrus's edict seems to have concerned mainly the population of the ancient kingdom of Judah exiled from Jerusalem, rather than the entire Jewish Diaspora scattered across the Medo-Persian Empire. According to the Scriptures, the Jewish governor Zerubbabel brought forty-two thousand deportees back to Jerusalem, accompanied by the prophet Haggai. This was the first wave of the period of exile, around 538 BC. The city and Temple were then rebuilt, despite the difficulties caused by local populations hostile to the Jews. The dedication of the Temple did not take place until seventeen years later, during the reign of Darius I, third king of the Achaemenid Empire (Ezra 3,10-13).

Image opposite: an amphora handle in the shape of a winged ibex. 4th century B.C. © Théo Truschel.

The organization of the Empire and the death of Cyrus

The organization of the Empire and the death of Cyrus

A military genius and a fine diplomat, Cyrus II organized his immense empire in a remarkable way, using the satrapy system inspired by Assyrian administration. He added to this a spirit of flexibility and tolerance towards the various national peculiarities, which helped to preserve peace in this gigantic edifice. Cyrus is credited with establishing Aramaic as the official language and spreading it throughout the empire.

Image opposite: the daric, a gold coin used in the Achaemenid Persian Empire and its sphere of influence. © DR.

He is buried in Pasargadae (in present-day Fars, a province in south-west Iran), which he had made one of his capitals.

In 1971, the United Nations had the Edict of Cyrus translated into all languages. The cylinder sets out the fundamental principles of Persian law: religious tolerance, the abolition of slavery, freedom of choice of profession and the extension of the empire.

Image opposite Cyrus II the Great: Cyrus II the Great is buried in Pasargadae (in present-day Fars, a province in south-west Iran), which he had made one of his capitals. His tomb remains to this day. Gilles Rheims.

One of the staircases leading to the palace entrance in Persepolis, Iran. Built around 521 BC by Darius I, one of Cyrus II's successors. Leonid Andronov.

Gold jewelry. 6th century B.C. Leiden Museum © Théo Truschel.

Gold jewelry. 6th century B.C. Leiden Museum.

The situation of the Judeans

The situation of the Judeans The organization of the Empire and the death of Cyrus

The organization of the Empire and the death of Cyrus