Bible, History, Archaeology

History,

Archaeology

The oldest complete book of Psalms

Contents:

Its discovery - Its condition - Its restoration - The origin of the Coptic word - Contents - Conclusion

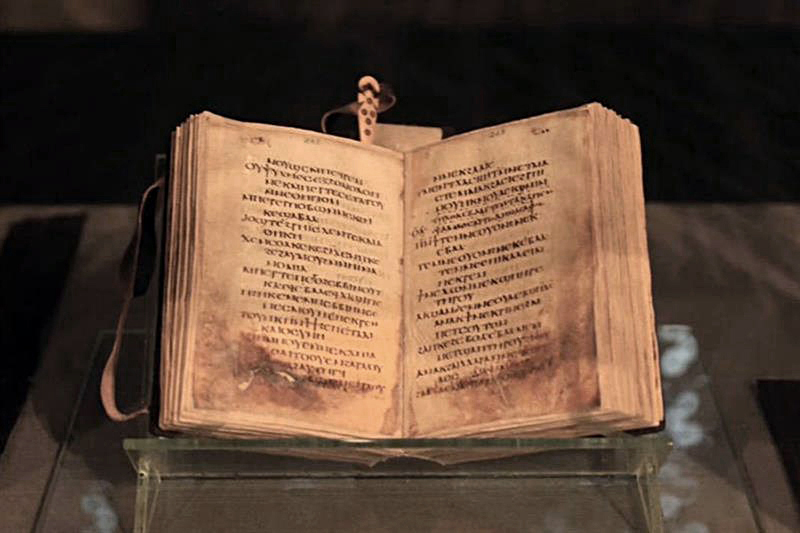

After five years of meticulous restoration work, the Coptic Museum in Cairo has once again exhibited one of the most precious of the Coptic artworks. artifacts of his collection: the Mudil codex, the oldest complete Coptic psalter ever discovered.

Its discovery

Image opposite: the Mudil codex after restoration. Public domain.

It lay in the grave like a pillow under a teenage girl's head. It was the only object buried with the girl, and of immense value. The purpose of such an arrangement is unclear, but it recalls the ancient Egyptian practice of burying the Book of the Dead with the deceased to ease their passage into the afterlife.

The Mudil dates from around the end of the 4th century A.D., making it the oldest complete book of Psalms. To date, no such ancient work has ever been discovered in Egypt, and there is no evidence of an authentic earlier book.

A view of the Nile in Middle Egypt with a felucca (originally from Greek epholkion meaning small boat) whose design has hardly changed since Antiquity. givaga 1901779558.

Its condition

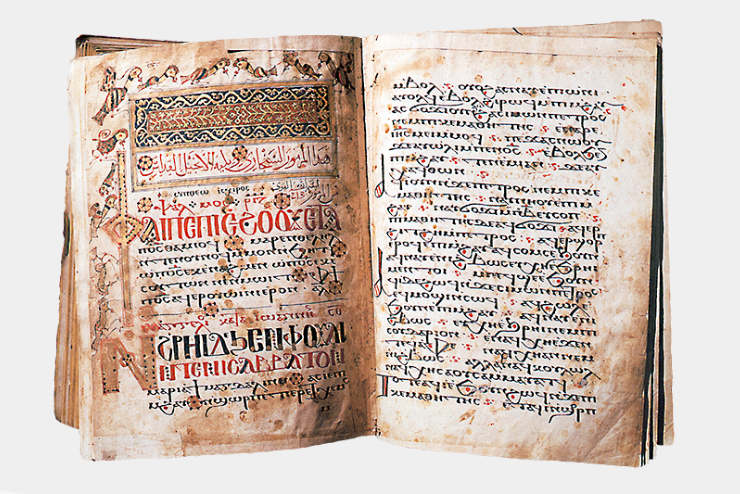

Image opposite: 14th-century Coptic liturgical book containing verses 24 and 25 of Psalm 118 © Théo Truschel.

Image opposite: Egyptian Christians, known as Coptic Christians, used a cross similar to the ânkh. The cross used by early Egyptian Christians is known as a «crux ansata», meaning «cross with a handle» or «annealed cross» in Latin. Public domain.

The manuscript had also suffered various damages, including the detachment of its pages due to the deterioration of its binding, and most of the pages were wrinkled and dried out.

Today, the Coptic Church brings together several million faithful who come to pray fervently in churches founded in the 4th century. Here, during a mass in a church in Old Cairo. Sun_Shine.

Catering

Catering

Despite favorable environmental conditions, which have preserved the codex for over one and a half millennia, the manuscript was in desperate need of special treatment. Over the past five years, a team of Egyptian curators from the Coptic Museum and the Museum of Islamic Art have been working to remedy the various forms of damage resulting from ancient use and contact with the corpse.

Image opposite: the complete codex with binding and cover after restoration. Public domain.

The entire book had to be dismantled to enable all the pages to be carefully numbered and the binding repaired. In the course of the restoration process, digital UV and infrared images were produced, as well as photographic documentation, and specialists in codicology and Coptic texts were consulted.

The origin and meaning of the Coptic word

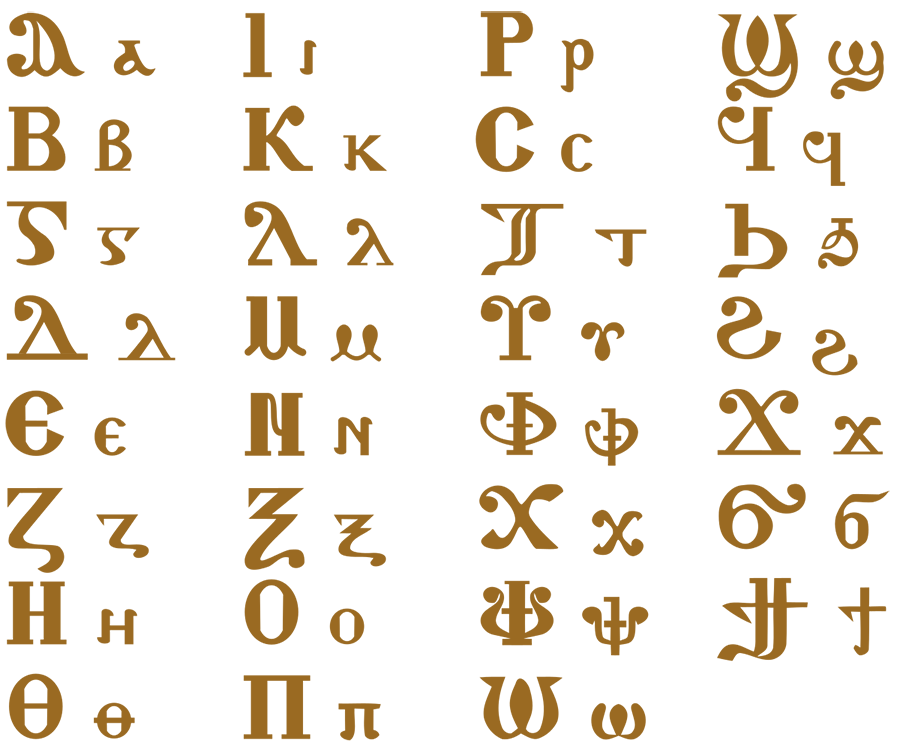

Image opposite: Coptic alphabet.

In 641, the Arab conquerors took over the name aiguptios which soon became abbreviated to Qibt (قِبط), i.e. Coptic.

The name Coptic was first used to designate the Egyptian population as a whole, then, as people converted to Islam, exclusively the members of the Christian Church of Egypt..

The Coptic language is the latest stage in the evolution of ancient Egyptian. Several regional Coptic dialects existed: Bohairic, Sahidic, Fayumic, Oxyrhynchite, Akhmimic and Lycopolitan.

Only Bohaïric, which has become a dead language, is still used, but only in liturgy.

Contents

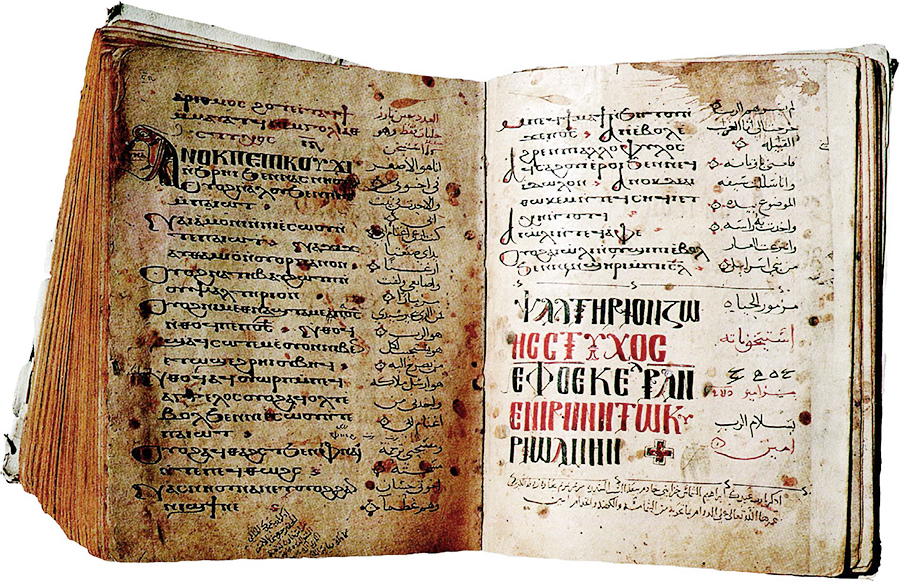

The last two pages of the apocryphal Psalm 151, dedicated to David's fight against Goliath: «[...] I went to confront the Philistine. He cursed me with his idols. But I tore off his sword, beheaded him and washed the children of Israel clean.»

Twelfth-century manuscript in Coptic and Arabic. Coptic Patriarchate Library.

The Mudil codex is important not only because it is the oldest and most complete version of the Book of Psalms in Coptic, but also because its text differs from other contemporary or later Coptic translations of the Septuagint Psalms, thus adding to the history of the transmission of the texts. Two main questions are raised:

1. What were the original texts for this translation?,

2. How was it revised?

In fact, the artifact contains some linguistically difficult passages and curious readings.

It's also important to consider that, unlike so many manuscript discoveries (including much of the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Gnostic Nag Hammadi Library), this codex comes from a controlled excavation.

Conclusion

Image opposite: the Coptic Museum in Cairo.

The Coptic Museum, founded in 1910 by Marcus Hanna Simaïka Pacha, is the world's richest museum of Coptic art, thanks to a collection of objects, fabrics, icons and manuscripts, the core of which includes artifacts produced between the 4th and 20th centuries. Nearly 16,000 pieces, arranged chronologically, are displayed in twelve different sections. Public domain.

The Mudil artefact is one of the Coptic Museum's most precious manuscripts to date, and will be on display again in a specially designed room in February 2024.

Catering

Catering