Bible, History, Archaeology

History,

Archaeology

Home > Historical figures > Figures of the TA > Egypt >

The Hyksos

Introduction

Who are the Hyksos?

Is their reputation as foreign invaders justified?

What do we know about them today?

Visit Hyksôs or «foreign country chiefs» (héqaou-khasout) is the name given to the kings of Avaris in the eastern Nile delta by the 3rd-century Egyptian historian Manetho, a term taken up by Flavius Josephus in his Against Apion ; This fanciful term described them as «shepherd kings» who invaded Egypt, likening them to the Bedouins of Sinai or Arabia. The name comes from two stelae discovered at Karnak, which recount Kamose's «War of the Year 3», a tale composed by the king's scribes to glorify him after the capture of Avaris. The origins of the Hyksos are still uncertain, but they seem to have come mainly from southern Canaan, and more hypothetically from northern Canaan.

The Hyksos and the biblical story of Joseph, son of Jacob

According to Manetho's chronology - which is, however, open to question - the Hyksos are thought to have lived during the Second Intermediate Period (circa 1700/1550 BC), but the presence of this type of population is attested as early as the end of the 3rd millennium. Biblical tradition places the story of Joseph's arrival in Egypt and his elevation to the rank of vizier in this period, but without specifying the name of his reign. In this context, power entrusted to an «Asian» foreigner is by no means impossible (an article on this subject, currently in preparation, will be published shortly).

The Nile delta is the area in Egypt where the Nile flows into the Mediterranean Sea. This marshy region has been rich in flora and fauna since ancient times. For almost 5,000 years, the delta has been an area of intensive agriculture. Egyptian papyrus comes largely from this region. It lies in the north of Egypt, starting just north of the city of Cairo, some 150 km from the Mediterranean coast, in a place the Egyptians call «The Belly of the Cow» (Batn el-Baqara). After a journey of almost 6,600 km, the Nile divides into several branches. Its surface area is around 24,000 km2, making it the largest delta in the Mediterranean, ahead of the Rhône. keem ahmed 1600320940.

The origins of the Avaris kingdom

The origins of the Avaris kingdom

Situation in the Nile delta at the end of the 3rd millennium and the first half of the 2nd millennium:

This period is one of the least well known in Pharaonic history; two unitary monarchies succeeded one another, that of Heracleapolis and that of Ititaouy, both with limited resources over a small territory; in fact, these monarchies appear to have been divided into numerous small, more or less hierarchical local powers, and it is in this way that the kings of Avaris seem to have been dominant in the delta.

Image opposite: Hyksos scarab seal and imprint, 17th century B.C., 15th dynasty. This seal bears three signs: ‘A.N.R., which are found in various seals from the same period in no fixed order, sometimes mixed with ornamental signs. Some specialists interpret these signs as an inscription that includes the name of the sun god RÂ; others see them as signs that have no precise meaning, but which were engraved by «Asian» craftsmen as an imitation of Egyptian signs, without them having understood their meaning. Rina Viers / Alphabets Association.

In any case, it was at the end of the 3rd millennium that the role of Tell El Daba/Avaris as a crossroads was affirmed; excavations show that the pharaohs of Heracleapolis had founded a logistical and military hub at the crossroads of sea, river and land routes, as did those of Ititaouy (presence of royal agents in charge of units of measurement and the «House of Byblos»); Avaris was the terminus of the «Way of Horus», a land route linking the port to the Gaza region, 200 km across Sinai and beyond to Syria and Mesopotamia. There's plenty of evidence of very close and regular contact with the principalities of the Levant and their populations: a temple of Levantine design has been discovered at Tell Ibrahim Awad, and Sinai and Negev ceramics at Tell el Daba.

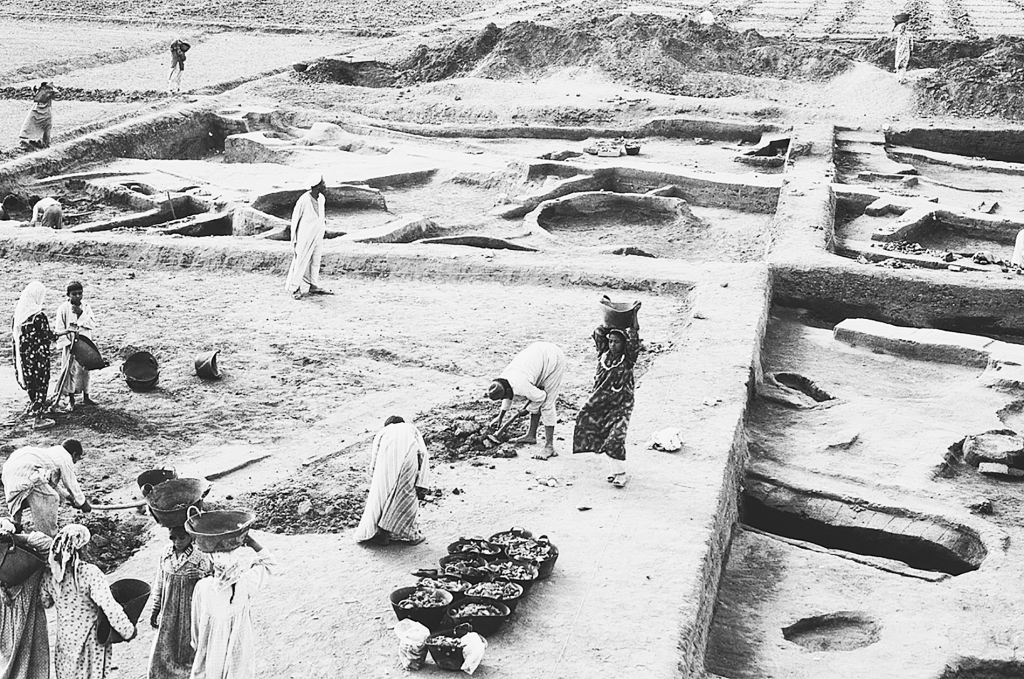

Image opposite: excavations at Peru-Nefer, the delta city of today's Tell ed-Dab'a. Since 1966, the site has been excavated by Austrian archaeologist Manfred Bietak and his team. The city was also called Avaris.

Work began in Zone F/I in autumn 1979 © M. Bietak / ÖAI.

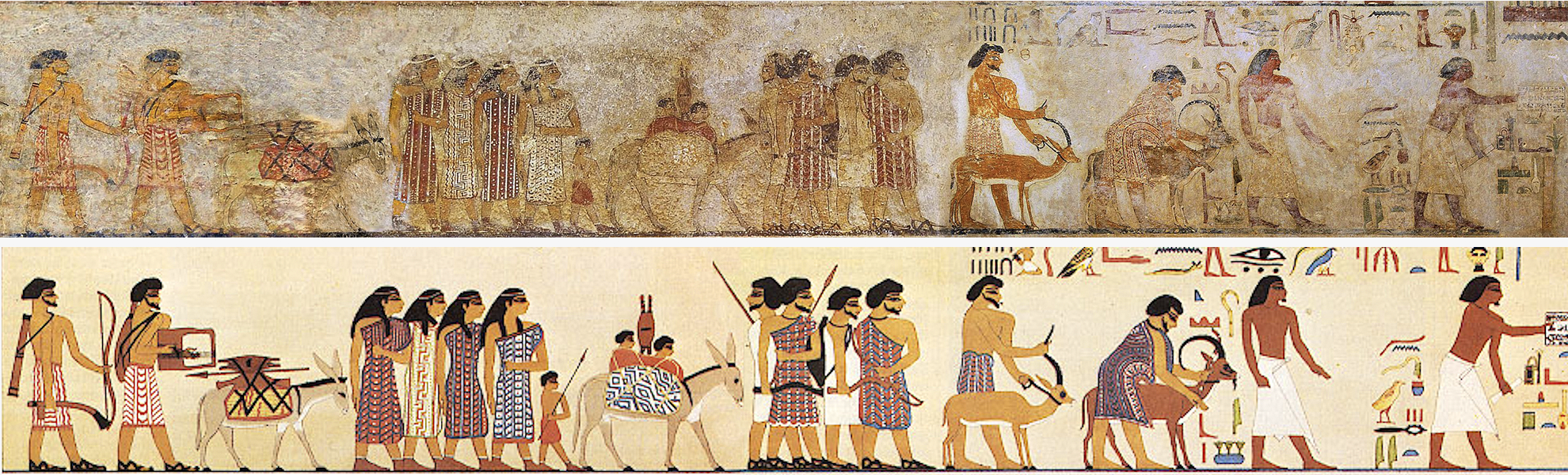

It seems, however, that throughout this period, the delta remained a region of scattered settlements with declining towns, traversed by pastoralists and independent populations from the Levant or Libya, farming and raising livestock from seasonal encampments. They also trafficked in minerals such as galena (for kohl and black dye), copper and turquoise from the mines of Serabit el-Kadim in Sinai. And the reality of these exchanges can be seen on the walls of the Beni Hassan tombs in Upper Egypt, where many Orientals are represented... Other minerals sometimes came from much further afield, such as tin (for bronze-making) or lapis lazuli from Afghanistan via Iran, Mesopotamia and the Levant. By this time, a network of trade was flourishing, linking Asia to Africa, the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean.

Image opposite: a gold diadem from an Avaris king unearthed during an archaeological dig. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Image opposite: a gold diadem from an Avaris king unearthed during an archaeological dig. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Another sign of the presence of Asian populations is the discovery of numerous «warrior tombs» in the arc of the circle from Sinai to the western delta; these are burials, sometimes under tumuli, of Levantine warriors accompanied by a rich array of weapons and one or more donkeys buried at the entrance to the tombs, the donkey still being the animal used by warriors and merchants at this time. Finally, we are beginning to see inscriptions describing households whose lifestyle was partly Egyptian and partly «Asian». Some of these Levantines were probably prisoners brought back to Egypt, but many were artisans, merchants, interpreters, sailors, soldiers and caravan leaders, forming a multicultural society based on trade and exchange. It is from this singular soil and not from an invasion of the region that the kingdom of Avaris draws its origins.

Serabit el-Khadim is a plateau located in the Sinai between the Saweg and Bata wadis. At an altitude of 850 m, it comprises several schistose layers, once rich in turquoise. Miners dug vertical shafts to gain access to the turquoise veins. It was on the walls of these galleries that Petrie discovered the first proto-Sinaitic inscriptions in 1905. At the eastern end of the plateau stand the ruins of a temple dedicated in Dynasty 12 to the cult of the goddess Hathor, «mistress of turquoise», with stelae over 2 m high. Other divinities celebrated included Soped, a local deity, and Ptah, the demiurge of Memphis © Rina Viers/Association Alphabets.

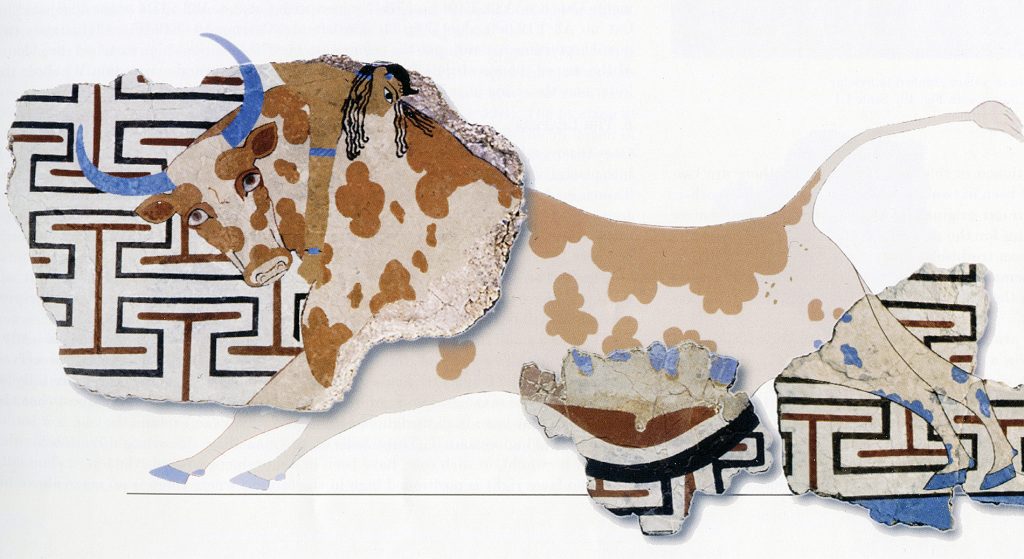

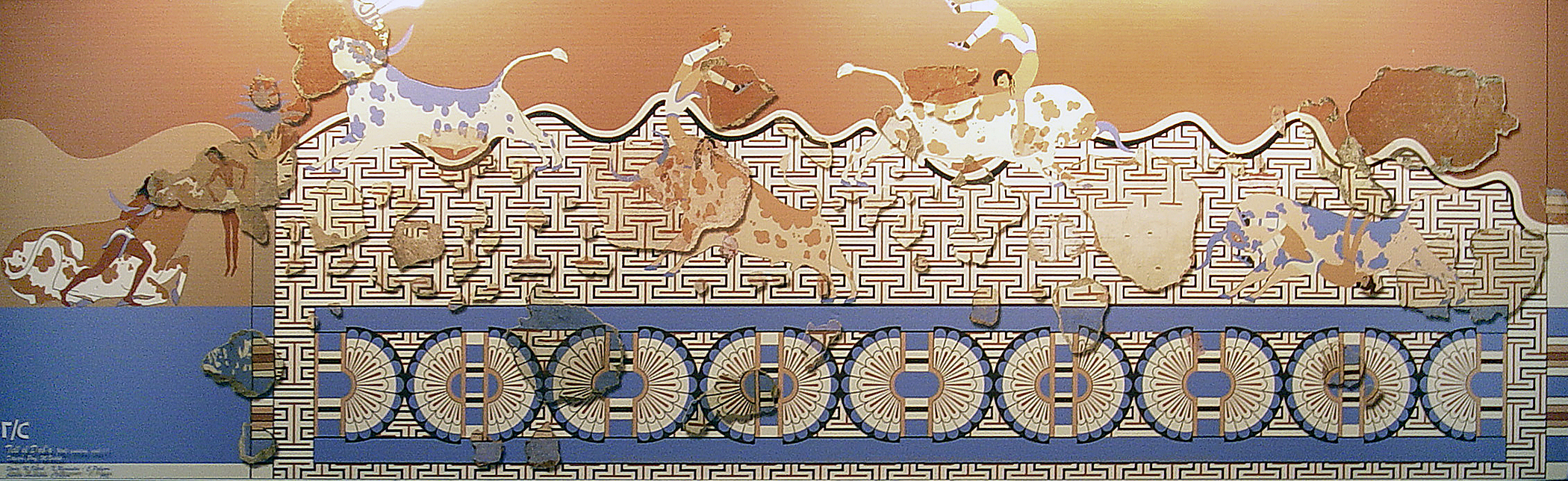

Minoan fresco reconstructed from debris found at Tell ed-Dab'a/Avaris (Peru-Nefer of Thutmosis III), Egypt. Now on display at the Iraklion Archaeological Museum, Crete, Greece. Licensed under CC-BY-SA-2.5.

It dates back to Egypt's 18th dynasty, probably under the reign of Hatshepsut (reigned c. 1479 - 1458 B.C.) or the temple that Thutmosis III (reigned 1479 - 1425 B.C.) had built on the site.

The paintings indicate Egypt's involvement in international relations and cultural exchanges with the eastern Mediterranean, either through marriage or the exchange of gifts. @ Martin Dürrschnabel, Benutzer: Martin-D1.

The golden age of Avaris

As the Ititatuy monarchy gradually faded, two kingdoms emerged in the 18th and especially 17th centuries BC. One was warlike, centred around Thebes, the other was commercial, centred around Avaris, its capital in the eastern delta. As long as the two kingdoms were separated by the swamps of Middle Egypt, they did not clash.

Image opposite: Reconstructed Minoan fresco from Avaris/Tell ed-Dab'a now in the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion, Crete. @ Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Crete.

The port site of Tell ed-Dab'a saw the establishment of a colony of sailors, merchants and shipbuilders from the Levant; their presence became so important that an original culture emerged, blending Egyptian and Levantine elements: burials were found within the dwellings themselves, which is an «Asian» practice; the size of sanctuaries, palaces and buildings increased, while banqueting halls appeared in the palaces, bringing together the king's allies.

Avaris was the transit point for imports to and from the Aegean (Cyprus) and Levantine worlds (including Byblos, an important staging post on the way to Mari and Mesopotamia): two million amphorae for oil and wine have been found at Tell el Daba/Avaris; trade also took place with Upper Egypt, Nubia and the kingdom of Kerma. The wealth of Tell el Daba is indisputable, according to the inscriptions of its conqueror, King Kamose: «Hundreds of ships loaded with gold, silver, lapis lazuli, turquoise, bronze axes, incense, precious woods and perfumed oils, all the beautiful products of the land of Retenou (= Canaan).»

Image opposite: a scarab bearing the name of King Khayan (circa 1620-1581 B.C.), one of the last kings of Avaris. Second Intermediate Period. MET.

The town of Charouhen, on the other side of the Sinai, south of Gaza, seems to be the kingdom's other major center: it lies at the junction of the caravan routes from the land of Canaan and east of the Jordan, and is therefore at the heart of the trade networks, a gateway to Egypt.

Listing the kings of Avaris and the length of their reigns poses insoluble problems, as Manetho's lists cannot be relied upon. The best attested king for the early period is Nehesy I («the Nubian»), a name that may be explained by his trade links with Nubia (seals found near the Second Cataract); we also have a list of some 50 kings of whom we know virtually nothing, some bearing Semitic names that betray their Levantine origin, several seals having been found on Canaanite sites.

Image opposite: Pharaoh Ahmose's head on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York @ Keith Schengili-Roberts.

The reign of Khayan (1610/1580), one of the last kings of Avaris, is the least poorly documented; his palace has been identified, with its furnishings and banqueting halls; his cartouche has been found in Babylonia, Central Anatolia and Crete. The last king of Avaris, Kamoudi, was overthrown by Pharaoh Ahmose (circa 1550/1525 BC).

The confrontation with Thebes and the end of the Avaris kingdom

Hitherto separated by the swamps of Middle Egypt, relations between the two kingdoms continued to deteriorate with the capture of Memphis by the Avarite king Apophis. The Thebans wanted to free themselves from the «servitudes» imposed by the Avarites. In the text of «the war of year 3» pharaoh declares «we can't stop without being squeezed by Asian taxes...» ; in fact, the Thebans wanted direct access to the Mediterranean and traffic with the Levant. The pretext found was that Kamosé wanted to be recognized as a «Great» by his neighbor, who inherited the simple title of «prince», thus an inferior. Kamosé (1555/1550) therefore launched an attack on Avaris with his army supported by a fleet; he apparently reached an agreement with the Hyksos, who left Avaris with their weapons and retreated to the other side of Sinai. It was then that the military operations were assimilated to a «national» struggle against a powerful «Asiatic» army of occupation: the myth of the Hyksos was established by the Thebans, the only «true» Egyptians.

A few years later, just as Kamoudi had retaken the city from Charouhen, Pharaoh Ahmose (1550/1525) came to lay siege to Avaris for a second time and succeeded in seizing the city, which was plundered before being delivered to the flames; the pharaoh crossed the Sinai and also seized Charouhen. This marked the definitive end of the northern monarchy.

The capture of Avaris gave the Thebans direct access to trade with the Levant and the Mediterranean, and the construction of a new palace gave them the financial and territorial resources they needed to assert their power.

The New Kingdom and its conquests began with Khamose.

The most famous scene from the tomb of Khnumhotep II (tomb BH3), one of the most beautiful at Beni Hassan. Khnumhotep recounts the history of his family, explaining the important functions they performed and his own administration of the nome; he also talks about his children and the construction of his tomb. The most famous scene is that of the arrival of the «Asians», in the sixth year of the reign of Sesostris II.

The two versions: the one above, as it stands today (this fresco is deteriorating year by year), and the one below, reconstructed on computer. Montage Théo Truschel.

The text was written by one of our authors based on the book : l’Égypt of the Pharaohs, from Narmer to Diocletian ; Damien Agut ; Juan Carlos Moreno-Garcia ; coll.« Ancient Worlds »Belin 2016.

Find out more

Damien AGUT, Juan CARLOS MORENO-GARCIA, L’ÉPHARAONS' GYPT: From Narmer to Diocletian 3150 BC - 284 AD.

Over the past thirty years, archaeological discoveries and the re-examination of ancient data have profoundly renewed our knowledge of ancient Egypt. These advances now make it possible to propose a new narrative, free from the routine of cyclical history where, between the necessarily sumptuous «empires», dark «intermediate periods» marked by the seal of decadence are interspersed.

ANCIENT WORLDS. Edited by Joël Cornette. Belin 2016.

The origins of the Avaris kingdom

The origins of the Avaris kingdom

Image opposite: a gold diadem from an Avaris king unearthed during an archaeological dig. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Image opposite: a gold diadem from an Avaris king unearthed during an archaeological dig. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.